Fascinated by Gallo-Roman history? Click Here to download > > > Here are 6 ways Rome affected France

- Home ›

- Destinations ›

- Loire Valley ›

- Chambord

Visiting Chambord Castle, France's Most Ambitious Renaissance Château

Published 6 February 2026 by Leyla Alyanak — Parisian by birth, Lyonnaise by adoption, historian by passion

Chambord Castle makes more sense once you know what it was built to do. This story looks at how the colossal building was meant to impress and how that affects the way you explore it now.

There's something about Chambord Castle.

A bit like the graceful Chenonceau, see it once, remember it always.

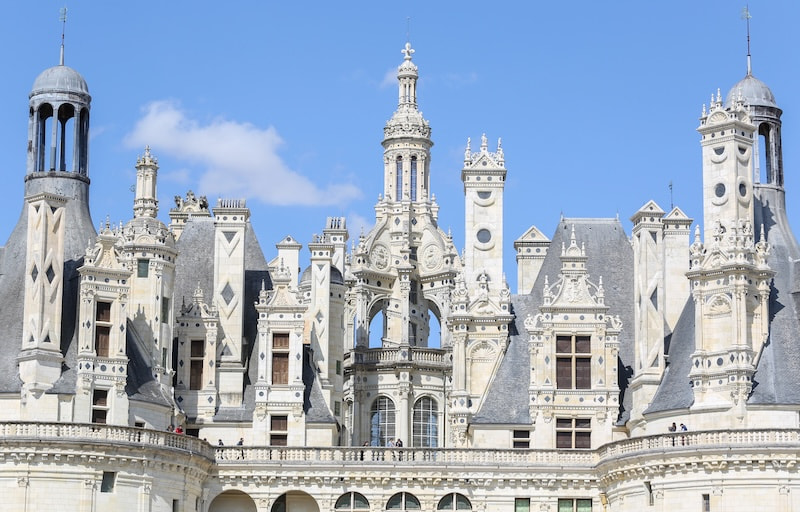

Perhaps it's the long approach, along miles of seemingly endless hunting forest. Or the sheer size of the château, the Loire Valley's largest. Or perhaps it's the silhouette, decorated with hundreds of chimneys and vast roofs of carved stone that stand out against the sky.

Probably, though, it's the renowned double-helix stairway, which two people can use without ever crossing each other's path and which "may" have been inspired by Leonardo da Vinci.

Whatever the reason, the Château de Chambord is as magnificent as it is memorable.

Just a little hunting lodge...

Why François I needed Chambord

Architecture and power at Chambord

9 Must-see features of Chambord Castle

- 1. The double-helix staircase core

- 2. The lantern tower above the staircase

- 3. The roof terrace: the “stone city”

- 4. The salamander ceiling in the François I apartments

- 5. The Greek-cross plan of the donjon

- 6. The unfinished feel of many rooms

Chambord after the kings: Revolution to WWII

Just a little hunting lodge...

Chambord wasn’t really designed as a castle to be lived in, and as soon as you walk in, you'll understand that. Visit in winter and you'll freeze, the cavernous rooms cold despite its 365 fireplaces, most of them extinguished.

But then, Chambord was never intended as a permanent royal residence.

King François I had something else in mind: he wanted a new château that would send a signal of power and authority and that was ambitious in scale. It should also be unique, covered in inimitable detail.

In 1519, his creation would begin to take shape, becoming one of the region’s most visited monuments, its profile recognizable around the world.

Beneath it all, Chambord Castle was built to send a message

Beneath it all, Chambord Castle was built to send a messageWhy François I needed Chambord

François I was young when he ascended the throne young and his claim to power wasn't exactly overwhelming (his accession followed the extinction of the main Valois line). His authority would depend in part on how he weighed up against other European rulers.

That comparison became obvious in 1519, when François competed with Charles of Habsburg for election as Holy Roman Emperor. Both campaigned heavily, but the electors chose Charles, who became Charles V. François now had a rival of similar age, whose territories surrounded France and whose prestige was far greater than his own.

It is against this background that he conceived Chambord Castle, not as a military showcase but as an architectural response, designed to position himself as the emperor’s equal.

Chambord also would be ideal for hunting, thought the king, an important consideration for a court culture built around the hunt. The surrounding forests were rich in wildlife and offered vast open spaces suited to mounted hunts and large court gatherings.

The architecture of power at Chambord

Earlier in his reign, at 25, François had led his army to war in Italy, where he came into direct contact with the art and architecture of the Italian Renaissance. Although the military campaigns had mixed success, the experience left a deep impression on the young king.

He returned home determined to bring Renaissance ideas to France and to assert himself as a cultured ruler on an equal footing with Europe’s major sovereigns.

Chambord’s design is the result of a deliberate mix (some would say jumble) of forms drawn from French medieval architecture and the Italian Renaissance.

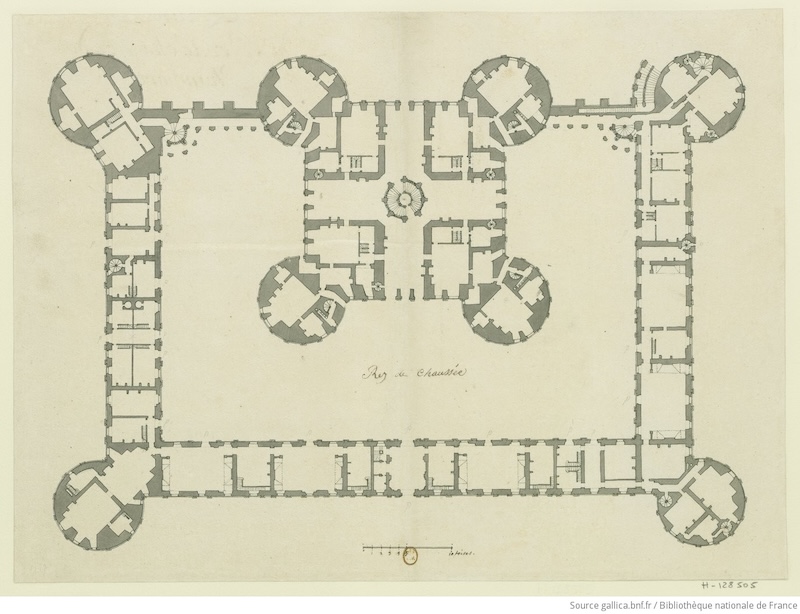

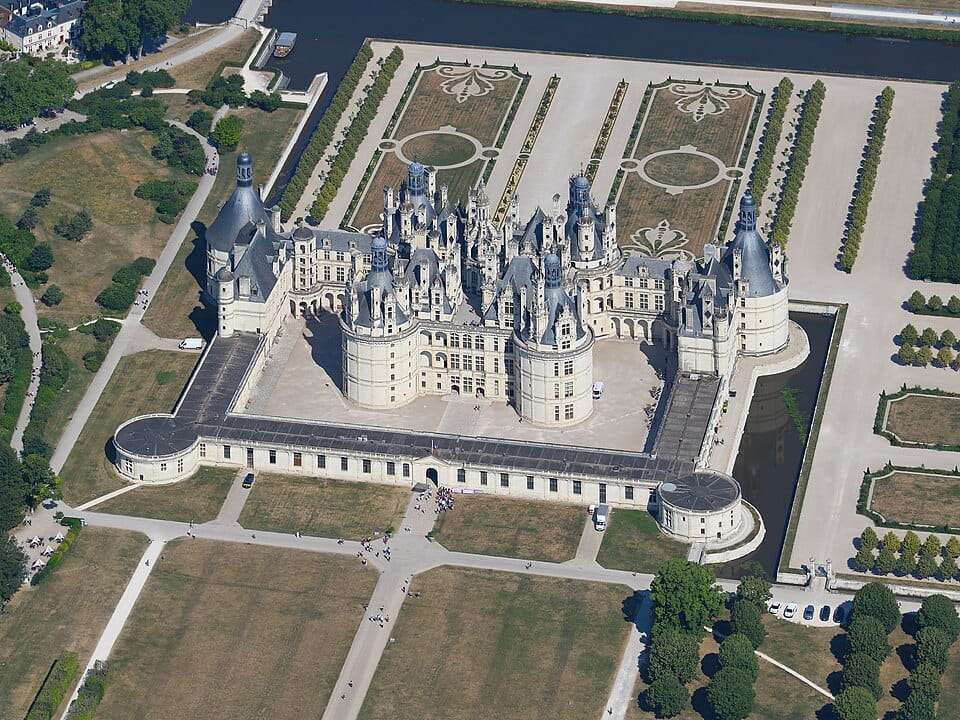

The château’s keep, or donjon, is square, organized around a centralized plan that was rare in France at the time. From this core extend four equal arms in a pattern called a Greek cross — a design previously used mainly in churches.

The so-called Greek Cross architectural plan

The so-called Greek Cross architectural planAlong the roof is a dense skyline of chimneys, each cut from pale Loire limestone. Each chimney is different, and many are decorative rather than functional.

Some historians suggest François I intended the roof as a symbolic crown, visible above the forest canopy.

Whether that was François I’s intent, the effect is unmistakable: Chambord trumpets its authority from afar.

WHEN FRANÇOIS INVITED HIS RIVAL TO CHAMBORD

François I didn’t build Chambord just for hunting. By the late 1530s, he needed a stage on which to reassert his authority after years of rivalry with Charles V.

François was especially bitter after his defeat at the Battle of Pavia in 1525 and his subsequent capture by Charles V’s forces. Taken to Spain, he was released only after agreeing to leave his two young sons as hostages for several years.

In December 1539, François received Charles V at Chambord while the château was still unfinished. The visit was a diplomatic move. By surrounding the emperor with ceremony and architectural glory, François was positioning himself as an equal rather than a former prisoner.

Charles may have been impressed, but relations between the two didn't particularly improve.

How Chambord was used

Inside, Chambord is full of passageways and secondary stairs, features that were designed for ceremony more than comfort. Rooms are large, often sparsely decorated, and rarely heated for long periods.

As you wander around these open spaces, remember that in those days, monarchs didn't necessarily stay in one place. François would arrive here with his large retinue, set up his furniture and tapestries, and repack everything to move onto the next stop once the hunting was over.

Think of Chambord more as a stage set than a home, and it will be easier to understand the building properly.

PRO TIP ➽ Chambord Castle has produced an excellent Histopad, or iPad, which shows you what rooms may have looked like in the 16th century. If you use the Histopad during your visit — and it’s worth doing — think of it as a tool for orientation. It will tell you where you are, what the room once looked like, and how spaces were used at a given moment in time.

What it won’t do is help you decide what really matters, or why certain details were designed.

How to interpret Chambord from the inside

The keep houses more than 60 rooms open to the public, including the royal apartments and the chapel.

This ceremonial bedroom of Louis XIV comes more than a century after François I began building the castle. Like his predecessor, Louis used the château only briefly, and the bedroom served mainly to signal royal presence during short visits rather than as a place of everyday living ©OffbeatFrance

This ceremonial bedroom of Louis XIV comes more than a century after François I began building the castle. Like his predecessor, Louis used the château only briefly, and the bedroom served mainly to signal royal presence during short visits rather than as a place of everyday living ©OffbeatFranceThe castle's 365 fireplaces often symbolize the days of the year – because they certainly don't help much with the heating. People here rarely warmed up in winter, and many of the fireplaces were rarely or never used. That hasn't changed today.

Chambord also boasts 84 staircases, if you count all types, from the famous double-helix staircase to secondary spiral stairs and service stairs, not to mention those used to access terraces and towers. No, Chambord wasn't designed for livability, but it was filled with symbols which occasionally gave it a mystical sheen.

6 Must-see features of Chambord Castle

These features are important because they reveal how Chambord was designed to be understood — as a political statement, not a comfortable home. Look for them even if you are using the Histopad.

1. The double-helix staircase core

The double-helix staircase is one of the first things people rush to see at Chambord.

François I may have enjoyed such inventions as a way to impress guests, but also to subtly showcase the sophistication of French engineering.

Chambord's double helix stairway ©OffbeatFrance

Chambord's double helix stairway ©OffbeatFranceStand at the base of the central staircase and look straight up. The hollow core runs vertically through the building to the lantern on the roof. The château's entire plan revolves around it and two people can go up and down without ever meeting – but they can see one another through the openings.

Some like to claim Leonardo designed it – he had after all been a guest of François I earlier in life. But there's no evidence that he had a direct hand in it, although it's not a stretch of the imagination that he might have somehow inspired it.

2. The lantern tower above the staircase

At roof level, the octagonal lantern caps the staircase shaft and turns it into more than a pathway – a vertical monument.

The lantern tower is the tall one right in the center

The lantern tower is the tall one right in the centerFrom here, François I could appear above his guests, silhouetted against the sky. The king quite literally occupied the center of the building — a political message of his power.

3. The roof terrace: the “stone city”

Walk the roof terraces and note the density of chimneys, turrets, and stair towers – you can get close to the chimneys.

No two are exactly alike. Many are purely decorative, since the building was never efficiently heated. The roof functions as a sculpted skyline — basically showing off surplus wealth and technical savvy.

4. The salamander ceiling in the François I apartments

Across vaulted ceilings and corridors you’ll find the salamander — François I’s personal emblem — repeated many times. This emblem stood for the king’s claim to rule with moral force and control over adversity.

Look for carved and painted salamanders paired with crowned “F” monograms.

Its motto was “Nutrisco et extinguo” — “I nourish the good fire and extinguish the bad.”

The salamander appears hundreds of times at Chambord, often a little different from one carving to the next but always recalling the royal presence

The salamander appears hundreds of times at Chambord, often a little different from one carving to the next but always recalling the royal presence5. The Greek-cross plan of the donjon

From any upper level, notice how the four wings radiate symmetrically from the center. This plan was almost unheard of in secular French architecture at the time and borrowed from sacred buildings.

By using a church-like plan for a royal residence, François I made the line between sacred authority and kingship less rigid, in an age of religious tension.

Aerial view of Chambord from the southeast, with the Greek cross shape perfectly visible. Photo by Carsten Steger, CC BY-SA 4.0

Aerial view of Chambord from the southeast, with the Greek cross shape perfectly visible. Photo by Carsten Steger, CC BY-SA 4.06. The unfinished feel of many rooms

Large spaces exist with minimal decoration or later additions.

This is not neglect. It reflects how the building was used so don't be surprised at the lack of gilding and décor we've come to associate with French châteaux.

Chambord after the kings: Revolution to WWII

After François I and the early Bourbon kings, Chambord wasn't used regularly.

Construction was finally completed under Louis XIV, and Chambord served for court visits and ceremonial events rather than daily life. In 1670, Molière’s Le Bourgeois Gentilhomme was first performed here for the Sun King and his court.

Then, in the 18th century, Chambord was used more as accommodation for high-ranking figures rather than a royal residence. Inside spaces were organized for short-term use, a bit like a luxury hotel, I'd like to imagine. As before, Chambord, impermanent, adapted to the times.

The French Revolution signaled a break. Chambord was looted, its furnishings sold, and much of its interior stripped of anything of value. The building survived largely because of its scale and isolation, but it didn't serve much use after it was emptied.

Preservation came with state ownership in the 20th century, and all those empty rooms would finally prove useful. When World War II broke out, Chambord became one of several sites used to hide priceless art treasures evacuated from Paris.

Chambord as a wartime refuge

In August 1939, as war approached, French authorities began moving major works from Paris museums to protect them from bombing and seizure. Chambord was virtually empty, so there would be room, and it was hard to reach, hence relatively safe.

Thousands of crates passed through the château, including works from the Louvre. Some stayed only briefly before being transferred elsewhere as conditions changed. After the war, the collections were slowly returned to their original museums.

This episode marked a final shift in Chambord’s role, from a royal statement piece to safeguarding national treasures. Today, exhibitions at the château have presented this history under the title Chambord, 1939–1945, focusing on the protection of cultural heritage rather than royal display.

Practical information for your visit

Because of its popularity, Chambord Castle is one of the easier ones to reach by public transportation, although there are plenty of other options.

Getting to Chambord Castle

Chambord is in Loir-et-Cher (Centre-Val de Loire region). By car it is about two hours from Paris. Rail connections run to Blois-Chambord station, and you can book your ticket here; from the station you can catch the Remi shuttle twice a day, or take a taxi to Chambord Castle (remember to reserve!)

Guided tours and extras

Guided visits run in English and other languages, including deeper access to hidden staircases and lofts. The Histopad is an optional add-on.

Advance entry tickets can include priority entry.

THESE CHAMBORD TOURS ARE HIGHLY RATED

- Day trip to Chambord, Chenonceau and Clos Lucé from Paris

- Private full-day tour to Chambord and Chenonceau (+ lunch) from the city of Tours

- Amazing hot air balloon voyage over the Loire Valley

Gardens and grounds

Chambord sits within a 13,500-acre estate of forest and gardens. The gardens were restored in the 21st century following historic layouts, while the wider estate remains a managed natural reserve. You can walk or cycle around it or use the canal that crosses the park.

VISITOR TIPS ➽ Arrive early to avoid peak crowds. Start with the central staircase and terraces, then move through the interiors. Allow time to walk in the gardens and forest paths. Parking and basic facilities are available on site.

Before you go...

Chambord is not simply a large Renaissance château.

It was designed to be a political and architectural statement, and project royal authority rather than domestic comfort. It reflects how François I used architecture for diplomacy, while later in history, its shift from royal accommodation to wartime art storage shows how the building’s use evolved each time political needs changed.

I’ve always found Chambord more interesting for what it represents than for how it looks. Initially built to trumpet royal authority, it later became tied to one of France's greatest royal failures. I explore that episode, and the man at its center, in a separate Substack piece for readers who want to go deeper into French history.

FURTHER READING ON THE CHATEAU DE CHAMBORD

- Chambord, Five Centuries of History (one of the authors is Stephane Bern, a favorite historians of mine)

- DK Loire Valley Travel Guide

- Rick Steves Loire Valley Snapshot

- Lonely Planet Loire Valley Road Trips

Did you enjoy this article? I'd love if you shared it!