Fascinated by Gallo-Roman history? Click Here to download > > > Here are 6 ways Rome affected France

- Home ›

- Culture & Civilization ›

- Roman France ›

- Vienne

5 Remarkable Vienne Roman Ruins Hidden in Plain Sight

Published 21 October 2025 by Leyla Alyanak — Parisian by birth, Lyonnaise by adoption, historian by passion

This guide explores the Vienne Roman ruins — including its temple, theater, forum, and the Saint-Romain-en-Gal site — to help you plan a full day in this ancient city.

If you love Antiquity, you'll be spoiled in Vienne.

Two thousand years ago, this was one of the great cities of Gaul: a trading hub and a political center, a staging post for Rome’s expansion northward, filled with temples, theaters, roads, baths, warehouses , all along the banks of the Rhône.

You won't have to go far to find them all – the temple sits on its original square, the theater is still a concert venue, and across the river, the mosaics of Saint-Romain-en-Gal wait to be explored.

They're all right there, within reach.

PLAN YOUR VISIT TO THE VIENNE ROMAN RUINS

Start at the Temple of Augustus and Livia (10–15 min) → climb to the Roman Theater (30–45 min) → continue to the Jardin de Cybèle (10 min) → cross the bridge to Saint-Romain-en-Gal (museum and site 1.5–2.5 hrs). Most of the route is walkable, though the theatre approach is steep.

Just as background, Vienne was populated by the Allobroges, a local Gallic tribe, when Rome invaded in 121 BCE. Seventy or so years later, it became a colony under Julius Caesar.

And fortunately for us – as is the case in Lyon, Arles or Nîmes, to name a few – there is plenty left to see. Vienne also happens to be an easy day trip from Lyon.

1. The Temple of Augustus and Livia

On its own, the Temple of Augustus and Livia would be enough reason to justify a visit to Vienne — it is one of the best-preserved Roman temples in the world.

In France, only a handful of Roman monuments are this complete: one in Nîmes, another in Vaison-la-Romaine, and this one.

Built between 20 and 10 BCE, it survived by sheer luck (and a bit of clever repurposing). When pagan temples fell out of use, it was converted into a church and eventually surrounded by houses, which protected it from demolition.

Centuries later, it was stripped of its chapels, turned into a library, and eventually became a public hall. Each time it changed its purpose, it survived that much longer.

In the heart of Vienne, the Temple of Augustus and Livia ©OffbeatFrance

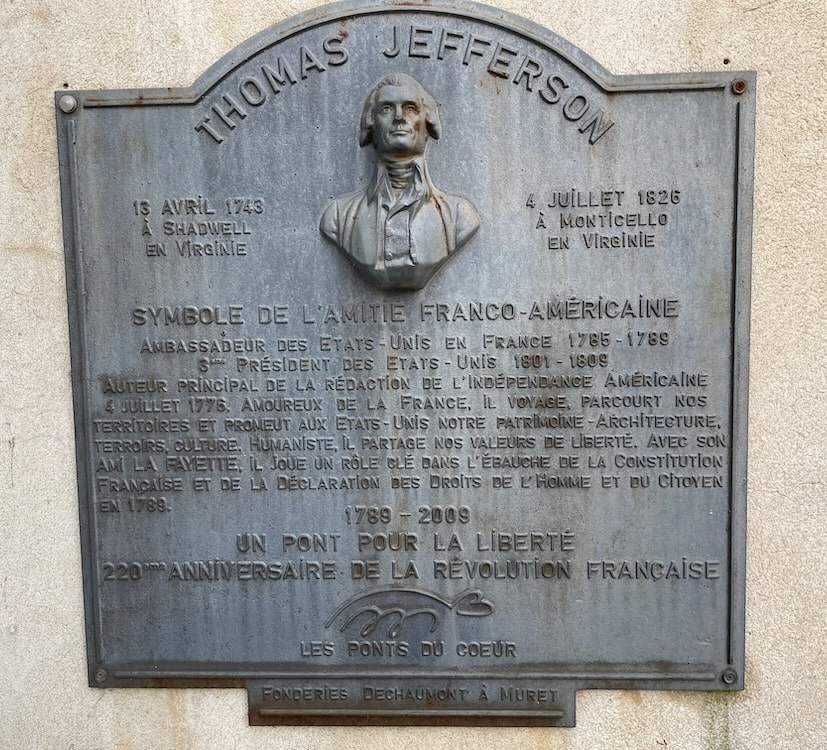

In the heart of Vienne, the Temple of Augustus and Livia ©OffbeatFranceInside the temple, there is nothing to see, the beauty of this building being its exterior of plain stone fluted columns (although some columns were clumsily replaced by concrete during the 19th century) and proportions so precise that Thomas Jefferson sketched it in 1787, using it and Nîmes’ Maison Carrée as models for classical architecture in America.

During the Jazz à Vienne festival, the temple opens its doors and welcomes the public for concerts, with saxophones and trumpets filling the void.

IF YOU VISIT VIENNE, FRANCE

- Here's where you can book your train tickets.

- For stays near the various Gallo-Roman sites, booking.com has flexible cancellation policies.

2. The Roman theater

A short climb up the hill from the temple brings us to one of the grandest reminders of Gallo-Roman Vienne, the theater, cut directly into the slope of Mont Pipet.

When it was built in the first century CE, it could hold up to 12,000 spectators, making it one of the largest in the Roman world. The sound design was just perfect: the natural curve of the hill acted as an amplifier, and the slope was calculated so that voices carried clearly from the stage to the highest row.

They still do – just try standing on the stage today and speak to someone way up the hill. They'll hear you.

Next to the theater is a smaller odeon, seating around 4000 people, probably used for readings and recitals.

Both were eventually abandoned, and as has happened to many ancient French ruins, their stones were carted off to build houses and churches lower down the hill.

In the 1920s, local architect Étienne Rey began restoring the theater with the meager resources he had at his disposal, basically small stones and local labor, not to mention plenty of persistence.

Now, the theater is again a living space. Every summer it fills with people for performances, the highlight of which is Jazz à Vienne. Instead of Latin verse, we have jazz.

3. The Jardin de Cybèle

Just below the theater you'll find the Jardin de Cybèle, a quiet patch of grass and columns that were once part of the Roman forum. It was filled with administrative buildings and temples, and citizens gathered under covered porticoes to trade or gossip.

The Jardin de Cybèle preserves part of Vienne’s Roman forum, with columns and foundations still visible in the middle of the city ©OffbeatFrance

The Jardin de Cybèle preserves part of Vienne’s Roman forum, with columns and foundations still visible in the middle of the city ©OffbeatFranceROMAN OR GALLO-ROMAN?

The two are often used interchangeably, but they do differ.

“Roman” refers to anything from ancient Rome itself, like its people or the Roman empire.

“Gallo-Roman” is the mix of Roman and Gallic that developed after Rome's conquest.

When we talk about sites or customs that arose in Gaul rather than in Rome, we should use “Gallo-Roman”. This applies to places like Vienne, Lyon or Nîmes. It's an oversight I'm often guilty of...

4. The Pyramid of Vienne

Down on Place Fernand-Point, another monument stands out for its uniqueness: the Pyramid of Vienne, a 15-meter-high stone obelisk that once stood at the center of the Roman circus.

It’s the only structure of its kind left in France – “Egyptian-style,” as early scholars liked to call it, though it probably had nothing to do with Egypt.

The 15-metre Pyramid of Vienne once stood at the center of the Roman circus ©OT Vienne

The 15-metre Pyramid of Vienne once stood at the center of the Roman circus ©OT VienneThe pyramid once stood on a platform surrounded by spectator stands used to watch chariot races. The circus is gone, and all we have left is the pyramid.

5. Saint-Romain-en-Gal

Cross the Rhône on foot and you'll reach Saint-Romain-en-Gal, which used to be the Roman city’s wealthy district and is now a major archeological site.

The ancient city

The seven-hectare site looks sparse at first glance – low walls and grassy plots – but appearances are often deceptive.

Under the lawns, there's a hidden treasure: several layers of ruins, discovered and deliberately re-covered for protection until archaeologists are ready to excavate further.

A peek at the ruins of Saint-Romain-en-Gal, across the river from Vienne ©P.Ageneau

A peek at the ruins of Saint-Romain-en-Gal, across the river from Vienne ©P.AgeneauIn antiquity this was a neighborhood of villas and gardens, lined with warehouses and paths.

The remains of a Roman road run toward the river, its surface worn uneven by centuries of traffic.

Beneath it, archaeologists have found a two-meter-high sewer, part of a complex drainage system that carried water and waste directly to the Rhône. Even the richest homes had plumbing — not bad for the first century.

The Roman road at Saint-Romain-le-Gal ©OffbeatFrance

The Roman road at Saint-Romain-le-Gal ©OffbeatFranceThe Gallo-Roman Museum

Once you've strolled around the excavations, it's time to visit the Gallo-Roman Museum, a modern structure that contrasts with its ancient surroundings.

Its floor-to-ceiling glass windows let you watch the Rhône and cast your eyes upon the ruined city – while admiring the stunning (and huge) mosaics.

The museum traces all facets of Gallo-Roman life in Vienna, as the city was then called (and not to be confused with Vienna, Austria): the river trade, crafts, commerce, cooking and tableware, the clothes people wore...

Top: Old Roman oven; middle: Mockup of warehouses that once stood in the Roman city; bottom: Example of an interactive exhibit. All these pieces are from the Gallo-Roman Museum ©OffbeatFrance

Top: Old Roman oven; middle: Mockup of warehouses that once stood in the Roman city; bottom: Example of an interactive exhibit. All these pieces are from the Gallo-Roman Museum ©OffbeatFranceThe mosaics restoration workshop

Vienne is so rich in mosaics that a vast 6000-square-meter workshop has been built to conserve them.

Mosaics from other regions are also brought here for cleaning or reconstruction before being returned to their original sites.

This is the tiniest corner of the enormous mosaic workshop hidden away below the museum ©OffbeatFrance

This is the tiniest corner of the enormous mosaic workshop hidden away below the museum ©OffbeatFranceAccording to Christophe Laporte, head of the museum's mosaic restoration workshop, bringing in these mosaics is both challenging and rewarding.

"You have to lift floors from the antique city in their entirety so they don't break, and then transport them to the workshop. Afterwards they are carefully cleaned and prepared for exhibition."

Christophe Laporte, head of the mosaics workshop, explains how mosaics are restored ©OffbeatFrance

Christophe Laporte, head of the mosaics workshop, explains how mosaics are restored ©OffbeatFrance"The patterns can range widely from the roughest cuts and simple black-and-white designs to elaborate geometric illusions and mythological scenes. Some delicate marble tiles are so thin it’s hard to imagine how Roman craftsmen cut and laid them," Laporte said.

Many mosaics are incomplete, while others are are filed away in the workshop because there's simply no room for them in the museum. I had the good fortune of being shown some of these treasures.

Mosaics at Saint-Romain-le-Gal come in all sizes and shapes – and conditions, like this partial piece ©OffbeatFrance

Mosaics at Saint-Romain-le-Gal come in all sizes and shapes – and conditions, like this partial piece ©OffbeatFranceThe lapidary tradition

Vienne’s relationship with its Roman stones is ongoing.

In the 18th century, local artist Claude-Louis Schneider began collecting fragments that were found during rebuilding projects — statues, inscriptions, sarcophagi — and placed them in the deconsecrated church of Saint-Pierre.

The result was one of France’s first lapidary museums, a slightly chaotic display of relics that had survived two millennia underground.

It's hard to imagine what Saint-Pierre might have looked like because today, the stones have been carefully removed for conservation ©OffbeatFrance

It's hard to imagine what Saint-Pierre might have looked like because today, the stones have been carefully removed for conservation ©OffbeatFranceThe church is one of the oldest in France, with origins in the 4th century with a 12th-century bell tower, and will be part of a new museum of Vienne's history.

Julie Chevailler, who heads the new museum project, says the new institution should see the light of day in 2029.

"What is special is that the church will form an integral part of the museum. It won't only be a venue but will actually be integrated into the exhibition."

Expect big mosaics and sculpture you can actually read, a clear timeline you can follow in one go, and enough screens to explain the tricky bits – without drowning the stones.

It is now closed for visits but keep it on your radar!

Before you go...

The Roman sites are spread across both banks of the Rhône and you should plan to spend a full day if you want to visit the theater, the temple, and Saint-Romain-en-Gal, all of which can easily be reached on foot.

Here are a few helpful resources:

- Museum of Saint-Romain-en-Gal

- Roman Theatre

- Tourist Office (Vienne Condrieu Tourisme)

Roman Vienne ruins aren’t showpieces but are part of the city itself. Wherever you go, you'll come across part of a column or piece of mosaic, embedded into the everyday life of Vienne. The Romans may be long gone, but... they haven't really left.

While visitors inevitably are drawn here by the Gallo Roman remains, there's a lot more to see, as you'll discover in my guide to Vienne and its treasures. Beyond Vienne, here are even more Gallo-Roman remains in France if you're an enthusiast.

Did you enjoy this article? I'd love if you shared it!