Fascinated by Gallo-Roman history? Click Here to download > > > Here are 6 ways Rome affected France

- Home ›

- Ze French ›

- Holidays & Traditions ›

- What the French Eat at Christmas

What do French people eat at Christmas? brace for a few surprises.

Updated 14 December 2025 by Leyla Alyanak

Ask French people what belongs on a Christmas table and you’ll hear remarkably similar answers. This article focuses on traditional French Christmas foods and explains how those dishes fit into wider French holiday food customs.

Some things on this list will be ultra-familiar, while others may make you scratch your head in confusion.

So really, what DO French people eat at Christmas?

The answer sits somewhere at the crossroads of traditional French Christmas foods, regional habits, and long-standing family routines.

It will come as no surprise that the French are super traditional when it comes to Christmas – in fact, a survey showed that given the choice, 9 out of 10 French would prefer a "traditional" Christmas dinner in France to something more innovative. Why am I not surprised?

Whatever is served (and we'll get to that in a minute), what doesn't change is the purpose of the main Christmas meal: getting together with family.

Christmas tree in Strasbourg by Claude Truong-Ngoc / Wikimedia Commons CC BY-SA 3.0

Christmas tree in Strasbourg by Claude Truong-Ngoc / Wikimedia Commons CC BY-SA 3.0French Christmas food traditions and holiday foods

As an aside, while Christmas is the family meal, New Year's is often reserved for friends. (Of course all these are generalizations and you will find plenty of exceptions.)

The main French Christmas meal will either take place at supper on 24 December or at lunch on Christmas Day. For many families, the French Christmas Eve dinner is the most important meal of the holiday, especially when it follows Midnight Mass.

There's no set time for it, although if it's on the 24th, it will usually end well before midnight so that families can attend mass. For some, this could be the only time they'll see the inside of a church all year...

WHAT IS LE RÉVEILLON DE NOËL?

The Réveillon de Noël is the traditional French Christmas Eve meal. The word comes from veiller, meaning to stay awake. Historically, families ate lightly before Midnight Mass, then gathered afterward for a long, copious meal that stretched into the early hours of 25 December.

Today, the Réveillon no longer requires church attendance, but the idea remains the same: a festive, generous dinner centered on foie gras, seafood, a roasted fowl, and a bûche de Noël.

Watch out for tricky French terminology. In everyday French, the word "Réveillon" on its own usually refers to New Year’s Eve (le Réveillon du Nouvel An). When speaking about Christmas, however, make sure you use the qualifier "de Noël". It matters.

In times past, the main meal often came after Midnight Mass. I hear some people maintain that tradition, eating from two in the morning until sunrise, but I personally don't know anyone who does that so it may not be that widespread...

Even after all these years, with my parents long gone, I still have a traditional Christmas meal every year.

The traditional French Christmas dinner and classic holiday foods

A traditional French Christmas dinner menu follows a predictable structure, even if individual dishes vary.

Of course there are several factors that dictate what French families will eat for Christmas. One of those is budget, especially these days with prices on the rise. Another is location, because many regionis have their own specialties.

There's also your own origin. Christmas may be a Christian holiday, but it is celebrated widely, and beyond Christians. What you eat, however, may change depending on whether you are from the Mediterranean or the Middle East so here, we'll focus on the MAIN traditional Christmas meal and a few regional specialties, and leave the wider variations for another time.

Again, according to surveys, the "traditional" French food list for Christmas includes:

- Foie gras

- Seafood and salmon

- A fowl, and often a turkey but not always

- A bûche de Noël

Let's look at each in detail.

A bûche de Noël

A bûche de NoëlFoie gras

While it is deeply ingrained in French culture, awareness of the controversies surrounding foie gras is growing, even in France, and people are taking note. Several cities have banned foie gras from their official menus, and more will undoubtedly do so. Foie gras producers are exploring humane methods of producing this delicacy, and everyday French are rethinking their consumption.

But the numbers continue to speak for themselves: 70% of the world's foie gras is produced in France, and 93% of French people eat foie gras.

However, when you combine the ethical factors with price – good foie gras can be extremely expensive – people may think twice about how often they eat it. For many, it is reserved for the holiday season, a delicacy sampled once or twice a year.

Either way, foie gras remains the most beloved traditional French Christmas food, with producers sending out their order lists months in advance.

Not every French household serves the most expensive versions of these dishes. Many families opt for chicken or duck terrines instead of foie gras, or replace salmon with smoked trout or other cured fish, so the meal itself is the same, but with adjustments.

Foie gras, by the way, is usually eaten on thinly sliced toasted bread (or brioche), accompanied by fig jam and a glass of sweet Sauternes.

A fancy fowl

Another immutable French traditional Christmas food is the ever-present fowl, often with chestnut stuffing (which you can make yourself with this recipe).

The most popular choice of bird used to be goose, if you could afford it, or even a pig, if you could not (yes, I know it's not a fowl but in some quarters, it was the traditional Christmas meat dish). Confit of duck was also a possibility.

The "discovery" of America by Europeans created an exchange of products in both directions, and turkey seems to have been part of that exchange. From its arrival in the boat holds of the Conquistadors during the 16th century to the Christmas tables of Europe appears to have been a relatively short leap.

These days, however, turkey rules, not only from tradition but under the influence of the United States. But I live in the Bresse region of France, where the best chickens in the country come from, so my preferred Christmas fowl is a Bresse chicken, or a "poulet de Bresse".

Bresse chicken, the only French chicken protected with its own designation of origin. This is exactly what I have for Christmas each year: it's from my own region, the Ain

Bresse chicken, the only French chicken protected with its own designation of origin. This is exactly what I have for Christmas each year: it's from my own region, the AinSeafood and salmon

Highest on the list of Christmas seafoods are oysters, once only available along the coast because of cost. Today, you can eat them anywhere and at most times of year, but Christmas is rush hour on oyster farms. They are eaten simply, with a squirt of lemon or a bit of shallot vinaigrette.

Those who can afford it will include lobster and other seafood, and a quick trip to your fishmonger's (la poissonerie) or to the supermarket will unveil piles of fresh seafood you won't see the rest of the year.

If you've never seen a platter of seafood arrive at a Christmas table, you haven't experienced the French Christmas tradition at its fullest.

For many families, seafood marks the beginning of a traditional French Christmas meal rather than the main course.

Smoked salmon, although consumed throughout the year, is popular at Christmas, either with the seafood or instead of it. Again, it wasn't always so – the custom dates back to the 1980s or so, when salmon farming became common and prices came down.

Seafoods you'll have for Christmas

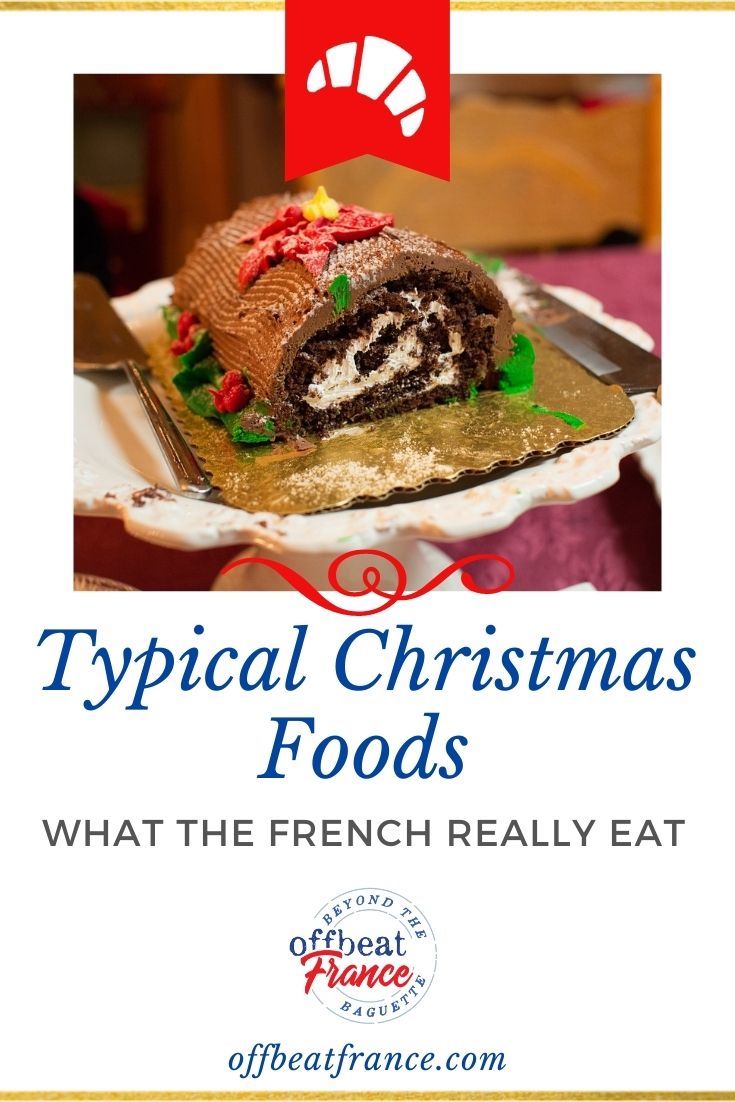

Seafoods you'll have for ChristmasLa bûche de Noël, the classic French Christmas dessert

The quintessential French Christmas dessert is the bûche de Noël, or the Yule or Christmas Log, a rolled cake with filling and thick buttery icing. In ancient times, legend has it that families would place a huge log in the fireplace and let it burn until the end of the meal. No other French Christmas dessert carries the same symbolic weight.

With the arrival of Christianity, the log would be set to burn until until 6 January. Should it go out before, you could expect tragedy in the coming year. The log remains, along with other superstitions linked to fire, an important symbol of ushering in the new year. But the eventual disappearance of huge fireplaces eroded this custom.

Then, during the 19th century, pastry chefs created a patisserie log, a cake that looked like a log but tasted like... cake. Several chefs have laid claim to inventing the cake, but no one knows when exactly or where it was created.

French Christmas cakes come in all sizes, from a small individual pastry to massive constructions designed to feed the entire household.

They can be standard cakes or ice cream cakes (try putting that in your freezer without squishing it!), and these days, you'll find them in a variety of flavours: chocolate, praline, coffee, vanilla, strawberry, and probably many more that my humble village patisserie doesn't stock.

One thing is certain: few self-respecting citizens will see Christmas through without their bûche.

Today, many home bakers recreate the tradition using a bûche de Noël mold rather than improvising the shape.

Chocolate!

Somehow this has made its way onto the French Christmas menu, either as small individual chocolates from the best chocolatiers, or as truffles – some families guard their truffle recipe jealously. This was a relative latecomer, however, since chocolate only arrived in France in 1615.

Anne of Austria (who was in fact the daughter of the king of Spain) brought chocolate from her native country and gave it as a gift to her betrothed, Louis XIII. It would take until Louis XIV and Versailles for chocolate to begin gaining wider appeal...

Today, when the French celebrate Christmas, chocolate is always part of "Le Réveillon de Noël", the Christmas Eve meal.

For those looking beyond supermarket boxes, French Christmas chocolates and artisan truffles have become popular holiday gifts in their own right.

The arrival of chocolate at court. La tasse de chocolat by Jean-Baptiste Charpentier (1768)

The arrival of chocolate at court. La tasse de chocolat by Jean-Baptiste Charpentier (1768)So what exactly goes on the French Christmas menu?

Taken together, all these dishes represent some of the most recognizable French foods at Christmas.

Whether served as a French Christmas Eve meal or as Christmas Day lunch, the menu structure remains largely the same, with plenty of adjustments and exceptions, of course. Here's what you can expect a traditional French Christmas dinner to look like:

- apéritif, usually champagne (and for children, a non-alcoholic Champomy) – and those who can afford it will add caviar to their Christmas dinner table

- entrées (remember, in France an entrée is the starter, not the main dish): this is where you have the foie gras and the seafood and smoked salmon and the oysters and the...

- a "trou normand", a Norman pause: this is a sherbet, of varying flavors, liberally dosed with alcohol; it is meant to clear the palate but is just an excuse for more drinking

- the main course, a fowl – often a Christmas turkey, but occasionally a capon, guinea fowl or even a top-flight chicken

- a cheese platter, although this is optional and not everyone feels able to eat cheese on top of everything else

- dessert: the bûche de Noël

- coffee and chocolates or truffles

- and this being France, there will be wine throughout! (and for anyone feeling lost, a straightforward guide to French wines and regions can be more useful than choosing a specific bottle).

Typical French Christmas menu served by restaurants. Hors boissons, by the way, means drinks NOT included

Typical French Christmas menu served by restaurants. Hors boissons, by the way, means drinks NOT includedSETTING A FRENCH CHRISTMAS TABLE

For many families, presentation matters almost as much as the food itself, especially for a long holiday meal:

- Champagne flutes or white wine glasses for the apéritif and seafood

- Large serving platters for shellfish or the main dish

- Linen napkins or a simple table runner for a formal table

What does Christmas time look like in French homes?

Probably not too different than it might in North America or England.

As a child, I remember having a Christmas tree (sapin de Noël) with plenty of decorations, a nativity scene, and an advent wreath.

I would anxiously await the arrival of Santa Claus, "le père Noël", who would bring small gifts (and possibly big ones) to be opened on Christmas morning.

Some of my friends opened theirs on Christmas Eve, which made my little-girl self extremely jealous, so one year my parents organized a personal visit by Santa: he appeared in my bedroom, all dressed in red and white, and pulled small presents out of his bag (it's a great gig for students!) It was an amazing event that I remember to this day.

My only disappointment was not being allowed to go up on the roof to see his reindeer...

Regional French foods at Christmas

While the structure of the meal stays consistent, regional French foods can determine what appears on the table.

France is a hugely diverse country – this diversity is one of the main reasons the French meal has been placed on UNESCO's intangible heritage list – so regional dishes will naturally have a place at the Christmas table.

Here are a few samples of regional Christmas dishes:

- Alsace: known for its foie gras and gingerbread cake, with honey and spices

- Burgundy: escargots, of course, along with Comté cheese from Franche-Comté

- Corsica: charcuterie, cheese and chestnuts (including chestnut polenta)

- Orléans and Champagne-Ardennes: boudin blanc, a white pork sausage

- the North: areas close to Belgium may well enjoy moules-frites (steamed mussels and french fries) for Christmas

- Provence: a tradition of 13 desserts (the 12 apostles plus Jesus) would include all sorts of local sweets, from nougats to candied fruit

- Southwest France: duck in various forms, with confit, magret or terrines alongside other regional specialties.

Candied fruit from Provence

Candied fruit from ProvenceFor readers curious about how these meals evolved, classic French holiday cookbooks (like this one from Alsace) often provide useful context alongside recipes.

A history of France's Christmas dinner

Today, when we all sit down for our meal, we tend to eat many of the same dishes, our habits shaped both by French Christmas traditions and by the food industry, which has made certain luxury products more widely available. As we unfold that linen napkin, we know we are about to overindulge.

But this overindulgence hasn't always been the norm. Nor has the single Christmas meal. Let's go back a little in history...

READ MORE: The Gaul Who Defeated Julius Caesar 🏛

Many of today’s French holiday foods took shape gradually rather than appearing all at once. So did the Christmas meal, which didn't start off being about Christmas, but about the winter solstice, which occurs on 21 December.

Back in Roman times, the population celebrated Saturnalia during the third week of December or so. It was held in honor of the god Saturn. Social differences melted away for a few days, slaves were temporarily freed, and mistletoe, vines or holly were used to decorate houses. And people ate.

Christmas may be considered Christian but it is truly celebrated worldwide.

Traditionally, a "repas maigre" or lean meal, was eaten in the lead-up to Midnight Mass as an act of penance. By lean we mean meatless, although fish was permitted but it was a light meal, a soup with bread, perhaps. Our oysters and salmon may well be holdovers from those days.

The Midnight Mass being a lengthy event, the main celebration came after the mass, so in the small hours of 25 December a "repas gras" or fat meal, one involving meat, was eaten.

This second meal came to be known as the Réveillon (it still is today). In one theory, it comes from the word "réveil", or awakening, as in staying awake until the festivities ended in the morning. In another, the "veiller" means to stay up, and the second meal, since it meant staying up a second time, was a "ré-veillon".

The French Christmas meal became more sophisticated in the late 19th century, during the Belle Epoque, as bread prices fell, allowing more discretionary income to be spent on meat.

In post-World War I rural cookbooks, pork is at the heart of the Christmas meal and while fowl is also highlighted, it's still a dish for the wealthy.

After World War II, however, Christmas recipes begin to flood the market, accelerating as the decades fly by and becoming increasingly complex – and luxurious. Under the influence of the USA, turkey displaced pork as the favorite Christmas meat.

Today's French Christmas eve dinner must, above all, be abundant. It's expensive, it's indulgent, but it's that one time of year when efforts are made not only from the pocketbook, but from the heart, a time of generosity and sharing and reaching out to those less fortunate.

FAQ

What is the main Christmas meal in France?

What is the main Christmas meal in France?

The main Christmas meal, called le Réveillon, usually takes place on Christmas Eve. It centers on foie gras, seafood or oysters, a roasted fowl, and a bûche de Noël.

Do French people eat turkey at Christmas?

Do French people eat turkey at Christmas?

Yes, turkey is common today, though it became popular mainly in the 20th century under American influence. Some families prefer capon, guinea fowl, duck, or regional chickens such as Bresse poultry.

Is foie gras still eaten at Christmas in France?

Is foie gras still eaten at Christmas in France?

Yes, but consumption is declining. Foie gras is still strongly linked to Christmas, a special dished usually reserved for the holidays because of its high cost and ethical concerns. Many families eat it once or twice a year rather than regularly.

What do French people eat on Christmas Eve vs Christmas Day?

What do French people eat on Christmas Eve vs Christmas Day?

There is no strict rule. Some families hold the main feast on Christmas Eve after church, others at Christmas lunch. The menu is more or less the same in both cases.

What is a bûche de Noël?

What is a bûche de Noël?

A bûche de Noël is a rolled sponge cake shaped like a log. It dates back to the 19th century and symbolizes the Yule log that once used to burn in French hearths during winter celebrations.

Do non-Christians celebrate Christmas in France?

Do non-Christians celebrate Christmas in France?

Yes, quite often. Christmas in France is often more of a cultural and family celebration. Many non-Christians observe it as a time for getting together and festive meals rather than a religious event.

Before you go...

Deepen your knowledge of France at Christmas by reading:

Did you enjoy this article? I'd love if you shared it!