Fascinated by Gallo-Roman history? Click Here to download > > > Here are 6 ways Rome affected France

- Home ›

- Culture & Civilization ›

- Roman France ›

- Vercingétorix and the Gauls

Meet Vercingetorix, The Chieftain Whose Gallic Warriors Beat Caesar

Updated 02 June 2025 by Leyla Alyanak — Parisian by birth, Lyonnaise by adoption, historian by passion

Vercingétorix − France's first hero? − led the Gauls to a rare victory against Julius Caesar before making a last stand at Alésia. Here, we explore the battle site, its rediscovery, and the Gauls' powerful role in French identity.

In the undulating heart of Burgundy, where vines dance in the wind, small villages dot the countryside, peaceful and serene, often oblivious to the momentous events that helped shape this country.

One of these is the hamlet of Alise-Sainte-Reine, an excellent day trip from Dijon, barely an hour's drive away. It looks calm now, but 2,000 years ago it was the scene of a battle most children in France still remember from school.

Back then, the village was called Alésia. Behind its walls, a group of Gallic warriors anxiously watched the Romans below, who had encircled them. The Gauls were led by a chief named Vercingétorix; the Romans, by Caesar.

How did the Gauls, fresh from a victory over Caesar, end up in this unfortunate dilemma?

NOTE: Pages on this site may contain affiliate links, which bring in a small commission at no cost to you.

How Vercingetorix beat Caesar, and how Caesar got his revenge

As you may know from all that reading of Astérix, the beloved French comicbook character (the books have been translated into 87 languages and are headed towards half a billion copies in sales), the Gauls were powerful warriors who constantly clashed with the invading Romans.

A depiction of Vercingetorix facing Caesar at the siege of Alésia. (Photo Lionel Royer, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons)

A depiction of Vercingetorix facing Caesar at the siege of Alésia. (Photo Lionel Royer, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons)Led by Caesar, a young pro-consul eager to prove himself, Rome's legions swept from victory to victory in what would become known as the Gallic Wars.

Which is why it came as such a shock when Caesar was defeated — not by another Roman general, but by a long-haired Gallic chief named Vercingétorix.

The year was 52 BCE the place was Gergovie in Central France, and the victor was this regal leader of the Arverni tribe, who had managed, if only briefly, to unite Gaul’s quarrelsome clans.

VERCINGETORIX PRONUNCIATION

Here's how to pronounce Vercingetorix:

Don't feel sorry for Caesar, because the tables were about to turn.

A few months after winning at Gergovie, the victorious Gauls again faced Caesar's troops, this time at Alésia. The Gauls were quite terrifying: noisy, their equipment gleaming, and taller than the Romans. Victory could be presumed.

Vercingetorix standing proudly next to Alésia - he may have lost but he's still a hero

Vercingetorix standing proudly next to Alésia - he may have lost but he's still a heroThis time, though, Caesar had learned a thing or two about the beer-drinking Gauls. After his miserable defeat at Gergovie, he changed tactics: rather than a frontal attack, he would besiege the Gauls and starve them to death.

The inability of the Gauls to dislodge Caesar's camp wore them down. Fearing starvation and overwhelm, the loose coalition that Vercingétorix had built began to splinter, and soldiers started drifting home.

In the end, after a brutal siege, Vercingetorix surrendered and was taken prisoner to Rome, where he was imprisoned for five years, and ceremoniously beheaded (or strangled, depending on the historian), a sad end to an illustrious career.

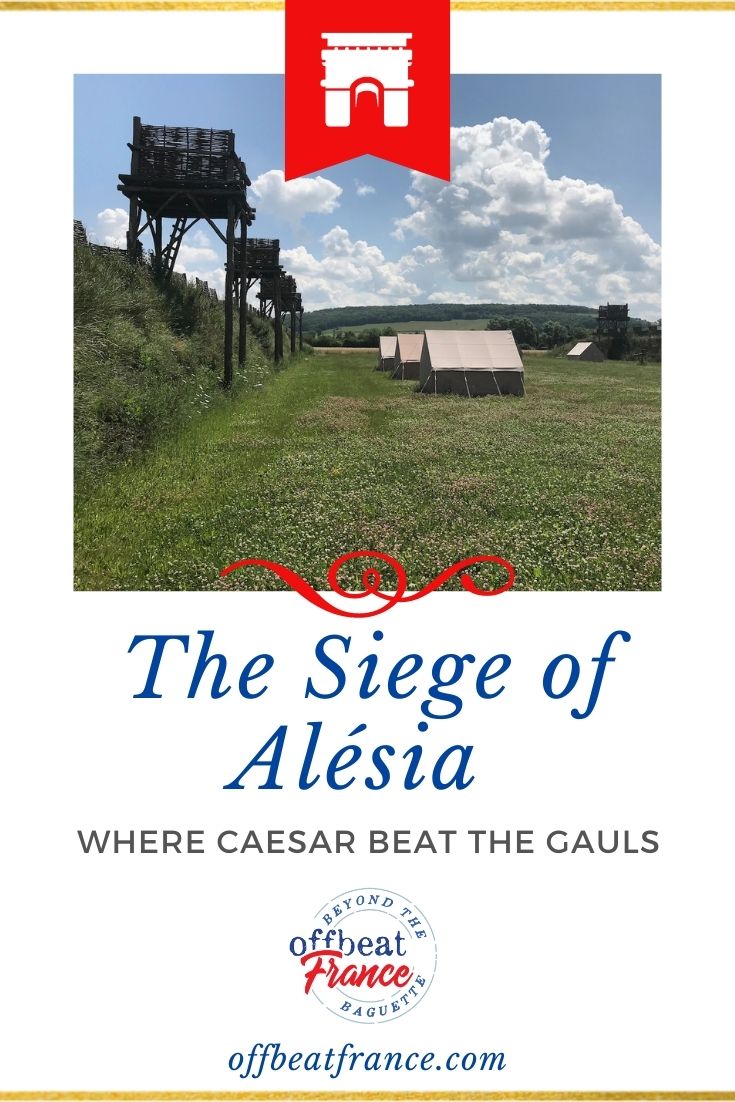

A re-creation of Caesar's massive fortifications: one faced Alésia and the other faced outwards, to prevent the Gauls from sneaking out or reinforcements from making their way in. They included watchtowers, fences, moats, and hidden traps which sprung up from the ground and pierced the feet of anyone unfortunate enough to step on one. Many mock battles are staged here each year to relive the event

A re-creation of Caesar's massive fortifications: one faced Alésia and the other faced outwards, to prevent the Gauls from sneaking out or reinforcements from making their way in. They included watchtowers, fences, moats, and hidden traps which sprung up from the ground and pierced the feet of anyone unfortunate enough to step on one. Many mock battles are staged here each year to relive the eventThe death of Vercingetorix would scuttle Gaul's opposition to Rome and pave the way for 500 years of Pax Romana, during which the two cultures would slowly meld, leaving us the many Gallo-Roman ruins still scattered across France today.

On a warm July day recently, I wandered around what is left of the ruins of Alésia, now an archaeological site. I gazed at the excavation site and wondered: what if the Roman siege had failed...

View of Alésia from the air, screengrabbed from a display at the Muséoparc Alésia

View of Alésia from the air, screengrabbed from a display at the Muséoparc AlésiaA few fun and curious facts about our Gallic warriors

It's almost embarrassing, but a disproportionate amount of our knowledge about the Gauls seems to come from that feisty little comic book character, Astérix.

If you've read the books, you'll know the Gauls ate lots of wild boar, loved large banquets, and consistently beat the Romans.

Well, don't believe everything you read because that last point, as we have seen, is not quite accurate.

For centuries, it was believed these long-haired, mustachioed warriors were wild barbarians, just waiting for Rome's civilizing mission to reach them.

It turns out this was not accurate either.

These may look familiar... but if you have some of these, yours might be in English

These may look familiar... but if you have some of these, yours might be in EnglishThe Gauls knew about learning and medicine

Not as much as the Greeks, but they did pass on their knowledge orally, discussed rhetoric, and knew about surgery, as did many warrior tribes.

The most learned individuals were the druids, who not only dispensed herbal medicine but also acted as judges and teachers, wise men bringing people together.

The Gauls were talented artisans

They were skilled at woodwork and metalwork, especially gold. They fashioned all those metal weapons and helmets and armor plates, along with cooking utensils and musical instruments.

The Gauls were inventors

This might come as a bit more of a surprise.

The Gauls cared about appearance and cleanliness and invented soap, using a mixture of ash and suet. They also invented the wooden barrel, later appropriated by the Romans – so much lighter and more convenient than those ridiculously heavy amphorae used to cart around oils and wine, don't you think? But then, the Romans had slaves to do all that...

The Gauls are also credited with inventing trousers and chainmail so yes, theirs was quite a brilliant civilization for the times.

The Gauls were relatively liberal

Women in Gaul had subordinate status, but not excessively so. They had their own property, and society didn't punish sexual straying, or at least, we haven't found any evidence of it.

Amorous relations between male warriors may even have been tolerated so yes, maybe not liberal as we know it, but nothing like the constrictions that would appear later.

But where did the Gauls come from?

The Gauls were a collection of Celtic tribes, each independent and with its own leaders, who originally swept down from northern Europe into the area roughly covered today by France and little parts of its neighbors to the north and east.

They spilled over the Alps into Italy and at one point even sacked Rome, which the Romans never forgot, eventually reconquering lost lands and pushing into France, beating the Gauls and setting up colonies along the way.

The Christian Era and the legend of Saint Regina

As for Alésia, its story didn't end with the Gauls.

Its modern name, Alise-Sainte-Reine, was bestowed in honor of two major historical events: the siege, of course, but also Sainte Reine, or Saint Regina, a young girl (either the daughter of a wealthy Gallo-Roman or a shepherd girl-stories vary) who lived around 253 CE and was eventually proclaimed a saint.

A recent convert to the new religion, Christianity, Regina rebuffed the advances of Olibrius, a Roman general. In a rather misguided effort to woo her, he poisoned her and then tortured her, eventually giving up and killing her. Beheaded her, actually.

At the spot where her head fell (these legends are often quite gruesome), a river spouted. A basilica was built on the site to venerate her and house her remains. (These were later transferred to the Abbey of Flavigny a few kilometers away and better known as the backdrop for the movie Chocolat.)

The site of what was once the Basilica at Alise-Sainte-Reine

The site of what was once the Basilica at Alise-Sainte-ReineThe tradition has been carried forward and even today, she is celebrated by the village's inhabitants, who reenact the tragedy of her martyrdom in the streets.

Thank you, Napoleon!

If you had been educated in France in the first half of the 20th century or earlier, you probably would have been told – even if you were from Africa or the Caribbean – that your ancestors were blond, blue-eyed Gauls.

Your history book would have started with these words: "Once upon a time, our country was called Gaul and its inhabitants, Gauls."

We now know that "Gaul" was a Roman construct, and the Gauls a scramble of Picts, Helvetes, and plenty of other Celts. During the Middle Ages, Franks, not Gauls, were considered our ancestors.

And Alésia and the Gauls might well have faded into oblivion had Emperor Napoleon III not been such a history fanatic.

For centuries, our historical focus was squarely upon the glories of our Greco-Roman past, not on some disheveled Celtic tribe which few people even knew existed.

It was only in the 1830s that scholars began digging into that faraway past, exploring the Gallic Wars and reviving the name of a long-lost hero: Vercingétorix.

It took Napoleon III's obsession with the past, and especially with Caesar, to speed things along: he dug up nearly all of Burgundy in a massive effort to locate the original site of Alésia.

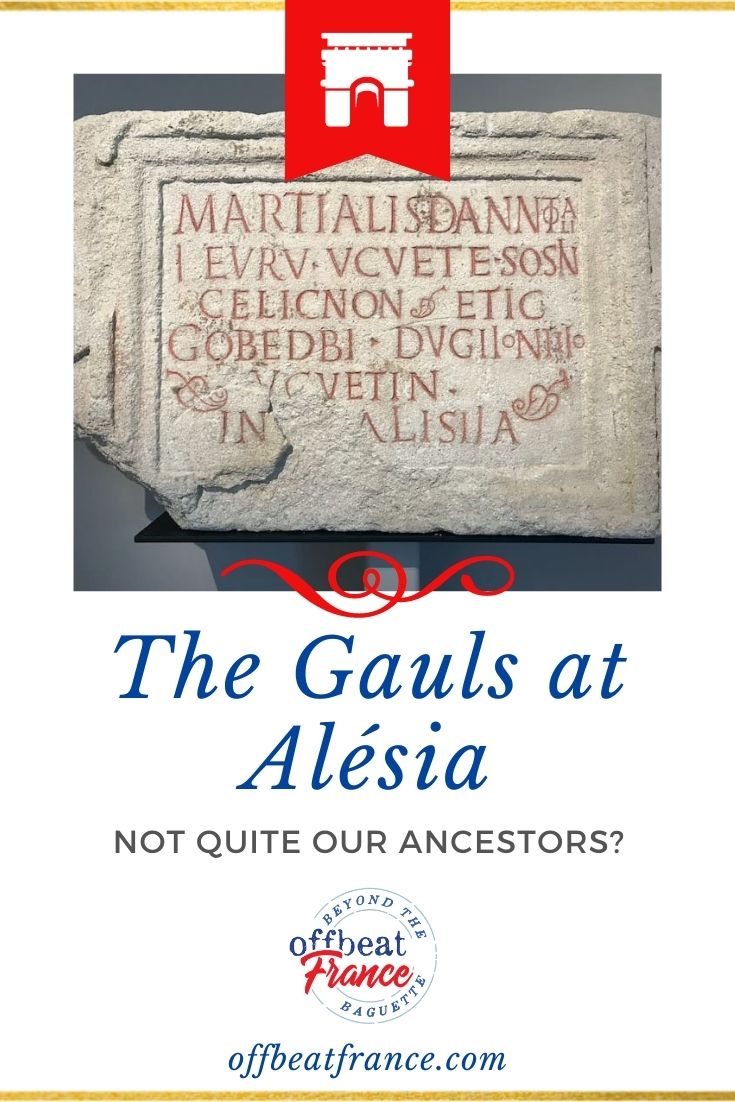

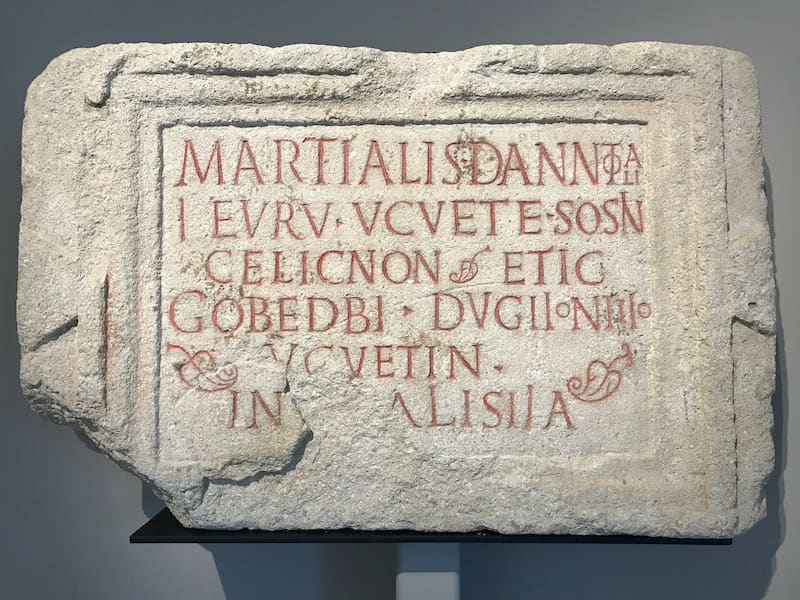

It may look Roman but this is written in the Gallic language, adding credence to the location of Alésia

It may look Roman but this is written in the Gallic language, adding credence to the location of AlésiaAfter France's ignominious defeat in the Franco-Prussian War in 1870, she was a country in search of a national story, one that would unify the bruised nation.

What better symbol than the Gauls resisting the Romans?

Building upon a newly discovered past, legends were woven, and so we came to be descendents of the Gauls, until the absurdity of it all came to light in the 1960s, where such an origin story founded on ethnicity could only encourage xenophobia and discourage diversity, not to mention be fatal to historical truth.

In the end, a middle way has positioned the Gauls as one of our ancestors, not the ancestors.

MuséoParc Alésia

If by now you're dying to know more, head to the Muséoparc Alésia, a museum where the histories of Gaul and Rome are told in intense detail, from what clothes were worn and instruments played to eating utensils and deities.

This modern, circular building is where the archeological wealth of Alésia is now housed and its duty is to bring it all to life for us.

The Museoparc's exterior - a modern setting for an ancient story. (Photo Carole Raddato from FRANKFURT, Germany, CC BY-SA 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons>

The Museoparc's exterior - a modern setting for an ancient story. (Photo Carole Raddato from FRANKFURT, Germany, CC BY-SA 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons>It is filled with displays that confirm Alésia's location (it has been much contested and often still lis), along with an impressive collection of artefacts - lance points, arrows, javelots, helmets, cheek protectors (paragnathids), coins, all excavated from Alésia.

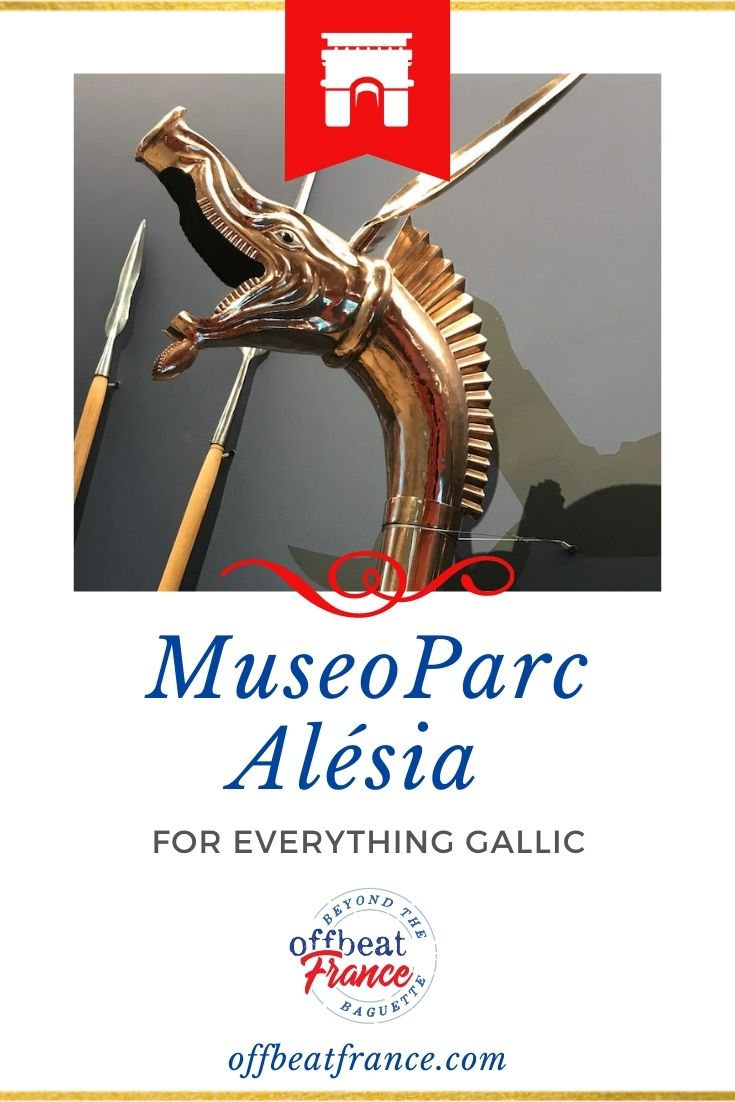

Below is my favorite, a war trumpet, or carnyx.

While the Gauls used musical instruments to help direct troops during a fight, this particular item was probably used more to frighten the enemy (I mean, that is one scary – but exquisite – trumpet!)

The Gauls used musical instruments to communicate with one another... this one, a carnyx, look more like something used to scare the enemy!

The Gauls used musical instruments to communicate with one another... this one, a carnyx, look more like something used to scare the enemy!The museum is designed to be accessible (it even won a prize) and descriptions are also in Braille.

The round shape, designed by architect Bernard Tschumi (author of the Parc de la Villette in Paris and the New Acropolis Museum in Athens), symbolizes the Gauls being encircled by the Romans, and through the windows and wooden latticework (also a symbol, but of the wooden Roman fortifications) you can see the oppidum of Alésia in the distance.

It's helpful to have all the maps, films, displays, scale models and multi-media features that bring Alésia back to life because, let's face it, it's hard for most of us to imagine an entire village based on a few stones jutting out of the ground.

A closer look at the Alesia excavation site

A closer look at the Alesia excavation siteYou'll probably need a car to get here because the museum is in the middle of the plain of Alésia, about a 45-min drive from Dijon, and the ruins at Alésia are up the hill, 3km/1.8mi away.

You could use public transport: take the train to Laumes-Alésia, and catch the bus LR122 to the museum (it won't take you to the Roman ruins, though). You can also walk here in ten minutes from the station.

If you're looking for something a bit more offbeat, you can play an escape game among the ruins, with 90 minutes to investigate and discover a secret. Throughout summer, there are plenty of re-enactments and festivals that will help bring this lesser-known historical period to life.

I would be remiss if I ignored the ongoing controversy about the location of Alésia, which some archeologists believe is in the Jura Mountains rather than in Burgundy. The Jura site has yet to be excavated, and officially, Alise-Sainte-Reine is Alésia, at least for most experts. This isn't for us non-academics to decide, but the controversy does come and go and needs to be acknowledged.

Today, the fascination with Gaul continues, whether we claim a direct descendence from these hirsute tribes or not. We've taken the Gauls to heart, and the word is meant to signal a certain authenticity, a traditional Frenchness. In fact, many foods and drinks and other products are called 'Gaulois'.

Vercingetorix and his Gallic warriors may have been abandoned by history until relatively recently, but there's no ignoring the Gauls now.

While you're here, you can also...

- Visit the gates and ramparts of Semur-en-Auxois and its medieval architectural heritage and drop by its eclectic museum (a world-renowned fossil collection sits one floor below three original paintings by Corot!)

- Explore the Château of Bussy-Rabutin and its extraordinary portrait galleries, whose garden is on the list of Most Remarkable Gardens of France.

- Drop by Flavigny-sur-Ozerain, site of the film Chocolat, but also on the list of the "Most Beautiful Villages of France" and home of the Anis de Flavigny, a candy factory located in the Benedictine abbey, where Sainte-Reine's remains were initially placed before being moved to the village church of Saint-Genest. The anise candy factory also has a fun museum and plenty of quirkiness, like this vending machine you could find in the Paris Metro in the early 20th century.

The anise vending machine that used to be in the Paris métro

The anise vending machine that used to be in the Paris métroDid you enjoy this article? I'd love if you shared it!

You might also like these stories!

Shop this post on Amazon

Pin these and save for later!