Fascinated by Gallo-Roman history? Click Here to download > > > Here are 6 ways Rome affected France

- Home ›

- Culture & Civilization ›

- Renaissance to Republic ›

- Château Bussy-Rabutin

Chateau Bussy Rabutin And The Salacious Count Who Lived There

Published 23 July 2021 by Leyla Alyanak — Parisian by birth, Lyonnaise by adoption, historian by passion

The Chateau Bussy Rabutin is one of the more unusual chateaux I've visited in France. Far from the ornate luxury of many others, this one contains... paintings, and of a most political nature.

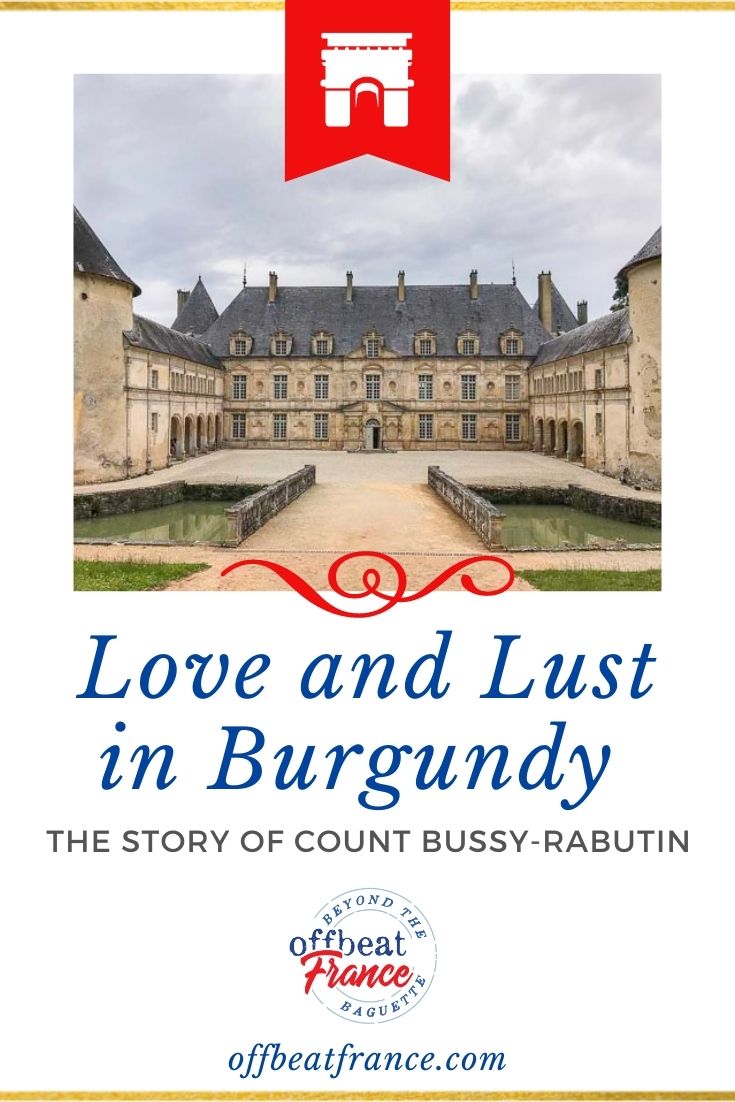

It takes a minute to catch sight of the Château de Bussy-Rabutin.

Your first glimpse of it will be from the side, and you may wonder why this discreet yet handsome manor is even called a castle.

Just follow the dirt path through the domain's centennial trees and a moat will suddenly appear. In the distance, behind the château, you'll be rewarded with a peek at the sumptuous gardens for which this place is so famous.

A quick turn around the corner and here it is, every inch a château. A fortress, actually.

But another surprise awaits.

A side view of the château, before you round the corner

A side view of the château, before you round the corner A different angle, on a less sunny day, but powerful nonetheless

A different angle, on a less sunny day, but powerful nonethelessNOTE: Pages on this site may contain affiliate links, which support this site. See full Privacy Policy here.

A surprising château

Usually, a Renaissance château will be filled with opulent furniture, its walls hung with tapestries and covered in plenty of stylish details that help us imagine what life was like 'back then'.

Not this time.

Of course there are some furnishings, and yes, you'll get your fill of curlicues and intricately painted beams and wood panels, but that is not what you are here for.

You've come for the portraits: portraits of soldiers, portraits of courtiers and VIPs and royalty, all crammed so closely together you might think they're copy-pasted.

Who are all these important people? And what are they doing on the walls of this rural Burgundy chateau?

The rise and fall of Roger de Rabutin, Count of Bussy

Once upon a time, at the court of the Sun King Louis XIV at Versailles, there was a certain gentleman of the name of Roger de Rabutin, comte de Bussy. He had been blessed with everything to succeed in life.

He took part in the colourful court's everyday goings on, the whisperings and gossip and mistresses, the furtive rendez-vous in garden nooks and behind the stairways.

Our count was a Lieutenant-General in the king's army, and a good one at that, although his quarrelsome disposition often got him into plenty of trouble.

He was a talented writer and thinker, and was even elected to the Académie Française, that esteemed institution designed to sustain the excellence of French language and literature. With only 40 lifetime members, being asked to join was quite the occasion for celebration.

Versailles in those days, contrary to what we might think, was not flowing and luxurious, nor was it particularly fun. It was, in fact, highly regimented, studded with a million little rules which, once broken, could turn an illustrious being into an instant outlaw.

As simple a faux-pas as attending the wrong ball, and you could be blacklisted. Stumble seriously, and you could be exiled. Or worse.

And now we come to the story of how poor Bussy-Rabutin became one of the fallen.

In 1659, at the height of his popularity (and dissolute lover-filled life), he took part in an orgy, where guests sang obscene versions of religious songs and baptised a pig. Let us not forget that Louis was a Very Catholic Monarch, and all this at a time when religion was already in turmoil, shaken by the Huguenots' protestant beliefs, and all within a context where witchcraft was never too far from the surface.

King Louis simply couldn't let this affront slide, and much as he may have liked Bussy-Rabutin, our libertine count was sent home to his château for some much-needed R&R.

As forlorn as he was about the exile, it could all have ended here, with a discreet return to court once his deeds had been expunged from memory.

But no. Things were about to get a lot worse.

The deed that cost Bussy-Rabutin his place at court

Probably in need of some intellectual stimulation and a little irate at having been sent home like a naughty boy, Bussy-Rabutin whiled away the time writing a booklet that would seal his fame, his fate, and rock his world: L’histoire amoureuse des Gaules, or, the Romantic History of the Gauls.

It was a satirical pamphlet, an insolent look at the loves and illicit affairs of the people who populated the court at Versailles. It was certainly not meant to be distributed in public: he had written it for his mistress, perhaps to cheer her up when she was ill, and a coterie of close friends.

Bussy let his pen run wild, describing the lasciviousness of the ladies at court and the exploits of the men, sparing no one, not the king, not the queen, not the most senior courtiers. He may have changed their names and circumstances, but the true perpetrators of the deeds he laid out were perfectly recognizable, both to themselves and, here was the problem, to everyone else.

His deft depictions, a dash of wit tinged with a dollop of ruthlessness, ensured him the enmity of most of those he described.

True, I confess, You are better than my mistress;

You have more beautiful hair,

Nothing compares with your eyes,

But even though you are far more beautiful

I don't like you as much as I like her.

—Roger de Rabutin, comte de Bussy

He regaled his readers with the affairs of the king and his then love, Marie Mancini, Prime Minister Mazarin's niece. In a staggering act of disloyalty, he even took a shot at Madame de Sévigné, the respected epistolarian and his cousin, with whom he may (or may not) have had an affair.

For reasons unclear (a jilt, perhaps?) a former mistress of his one day "borrowed" the book and painstakingly recopied it (photocopies, inconveniently, hadn't been invented yet), but with significant alterations. It then "somehow" made its way out of her hands, was quickly passed around court, inevitably landing on the king's lap.

The Sun King was understandably furious. Bussy tried to placate him by claiming his pamphlet had been altered by a "false friend". He showed the king the original manuscript, which somewhat mollified the monarch, but not for long. The royal anger soon took over and the king felt he had no alternative than to punish Bussy-Rabutin.

Again.

This time, Bussy was locked up in the Bastille for nearly a year, and then exiled to his château for another 17.

The king eventually relented and allowed the disgraced count to return to court and attend his "lever", the coveted royal waking up ceremony. But having slandered (or accurately described) so many courtiers, our humiliated count received a glacial welcome and soon scuttled back to his Burgundy refuge to lick his wounds.

He occupied his time by decorating his château with 500 portraits of France’s most important courtiers, former friends and colleagues, and former mistresses or women he had loved.

This was partly to keep busy, partly to enhance his château, and partly to get back at those he perceived had wronged him. Introspection was not his strong suit, and he gives no hint of ever blaming himself for his downfall.

Still, he could never dissipate the feeling of loss at the abrupt end of his much-loved military career, and his château gives off a sense of the pain and rejection he felt at being exiled from his erstwhile friends at court, as though life was something far away, being lived in his absence. As you walk through, you're bound to feel Bussy's nostalgia about his military life, his resentment against the king who exiled him, and his anger at the mistress who, when he was sent away, gave as good as she got and abandoned him.

This is not a château of pretty delicate things, but one of strong emotions and passions.

And what a château!

This striking Renaissance castle came into his family only a few decades before the pamphlet affair and was often renovated. In fact, the count, the third generation of his family to live here, refurbished the central section while he was actually living in it.

The main building is bordered by two wings, giving it a U shape that nests, very château-like, between four round towers.

Beautiful side view of the chateau on a sunny day. Photo courtesy Côte-d'Or Tourisme © E. CONTEJEAN

Beautiful side view of the chateau on a sunny day. Photo courtesy Côte-d'Or Tourisme © E. CONTEJEANOnce inside, allow your inner critic to emerge.

You'll be struck by the number of portraits in every room, probably painted by local (inexpensive) artists since exile had significantly squeezed the count's income. The paintings may not be major works of art, but they do tell the story of a life lived fully, though at a distance from court, and of the important people who gravitated around Louis XIV.

What also sets these portraits apart is that beneath them, you'll find a motto or aphorism referring to the painting's subject. These were rarely polite, usually true, and often highly caustic.

As you make your way through the castle, you'll find room upon room dedicated to certain types of Bussy's acquaintances.

You'll also find plenty of panels and painted woodwork, along with a few furnished rooms, but without a doubt, one comes here for the personages on the walls.

Salle des hommes de guerre (Warriors' Room)

Portraits and more portraits! Photo courtesy Côte-d'Or Tourisme © R. KREBEL

Portraits and more portraits! Photo courtesy Côte-d'Or Tourisme © R. KREBELThis room is a flashback to Bussy's much-regretted military career and to military heroes and geniuses, along with his interest in weaponry and his desire to cement his position as one of France's great military men.

His 65 warrior portraits include opponents and enemies, and here, as everywhere, mottoes abound.

Bussy-Rabutin's bedroom

At night, Bussy was well surrounded: from bed, he could gaze at 25 courtiers or courtesans or queens, his own mistresses, those of others, and those long gone who graced the walls of history.

The paintings include the lovely and intellectual Madame de Sévigné, whom, we have seen, was Bussy-Rabutin's cousin and possibly her lover, and her daughter, Françoise de Grignan (the Château de Grignan in the Drôme, north of Provence, is also worth visiting.)

La galerie des rois (the Gallery of Kings)

The Gallery of Kings is a long hallway with a ceiling of a green which might have been fashionable during the Renaissance but which today is a reminder of that unfortunate avocado green kitchen phase of the late 20th century.

Never mind the colour – the importance of this room is the portraiture that lines its walls, with 30 kings of France and dukes of Burgundy.

Here's how Bussy-Rabutin himself described it: "I have a gallery with the portraits of all the kings of the latest dynasty, from Hughes Capet to the king, and under each, a caption that tells you everything you need to know about their actions."

The cabinet of adages (or aphorisms, or maxims, or mottoes)

This little room is a marvel – 18 royal residences and monuments mixed in with allegorical panels that will have you scratching your head but will give you an idea of Bussy's witty style.

About a snail... "I close upon myself."

About an onion... "The one who bites me will cry."

About a rosebush... "I bend but don't break."

About Madame de Montglas, the mistress who dumped him when he went into exile... "Lighter than the wind."

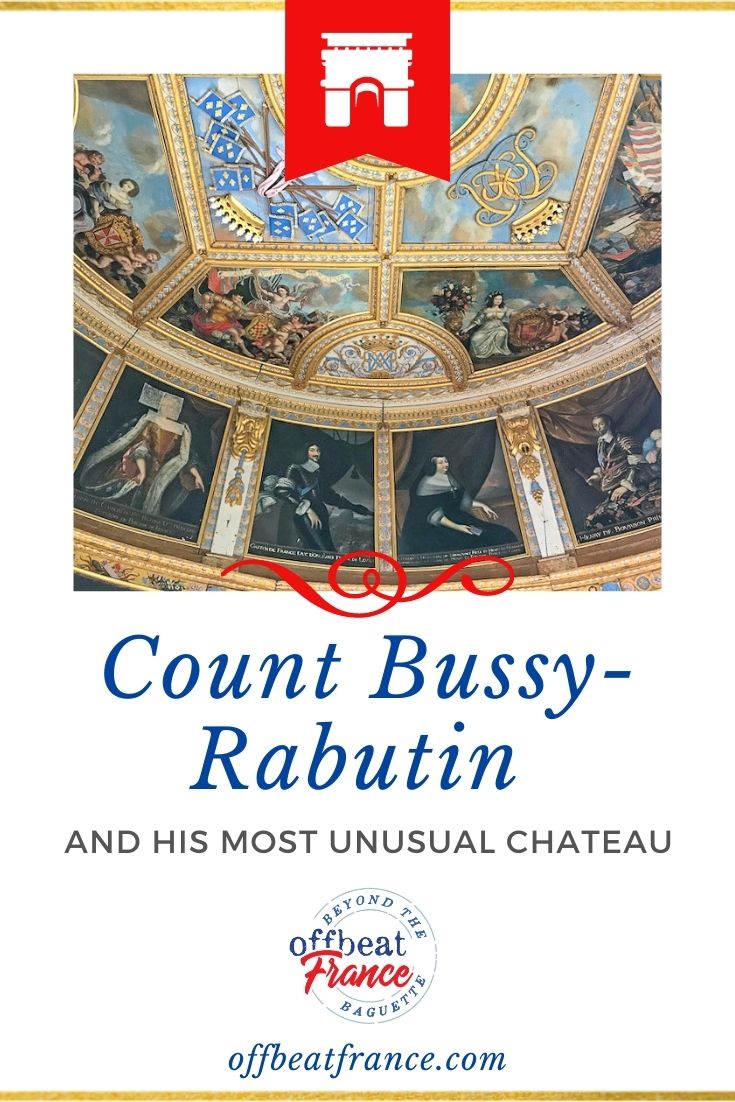

Cabinet de la tour dorée (the Golden Tower)

One of the gems of this château is the Tour Dorée, whose ceiling is a work of art decorated with 14 portraits of France's crème de la crème: Louis XIII, Cardinal Richelieu, Anne of Austria, Louis XIV, and more. If you notice any similarity with the Salon des Dames at Versailles, you wouldn't be mistaken.

Each portrait has its own description, but most of the sayings are untranslatable, already twisted with double meanings in the original French.

While Bussy commissioned many of his paintings, he acquired others directly from their subjects. As they went up on his walls with the requisite satirical maxims, some of the subjects may well have regretted sharing a portrait of themselves.

Take this one, for example: "If you want to love and not be cheated upon, fall in love with a woman made of ivory."

The gardens

Those remarkable gardens... Photo Côte-d'Or Tourisme © M. ABRIAL

Those remarkable gardens... Photo Côte-d'Or Tourisme © M. ABRIALThe garden is one of the château's spectacular features, restored in 1990 and now listed as one of the “most remarkable gardens of France”, with its labyrinth and pointed hedges and a large park with vegetable garden and fruit trees, bounded by water features and star-shaped alleys, complete with mythical statues, dovecote and apiary.

As was often the case in France, the château fell into disrepair and was saved from ruin in the 1830s by a new owner, count Jean-Baptiste-César de Sarcus, a cavalry captain under Louis XVIII, who restored all of Bussy-Rabutin's work and even wrote his own pamphlet – about the building, not its inhabitant – in 1854.

The building was bought by the government in 1929 and is now officially a historical monument. It has undergone constant restoration and in fact, when I visited, one of the wings was closed because of restoration work.

A few more tidbits about our esteemed count

One is torn between admiration for his pen, awe at his outspokenness, and dislike of his vitriol. Whatever his contemporaries (and ours) may think of him, this was no ordinary man.

- He was born of a distinguished aristocratic family in Burgundy.

- He was the third son, becoming head of the family after the death of his two elder brothers.

- He was 15 or 16 (depending on the source) when his father provided him with an officer's commission. He would rise to the third-highest military position in the land.

- His sojourn at the Bastille for attending the orgy was not his first visit to that august institution: he had already visited for five months when convicted of allowing unsupervised soldiers under his command to smuggle salt.

- His penchant for seduction (a skill he developed during military campaigns) was in no way hampered by the existence of his wife. After his wife's death, his debauchery would grow and several other incidents can be attributed to him, such as the kidnapping of a lady of the court (it did not end well, he was disgraced, and large sums of money changed hands to keep the scandal quiet). He did eventually marry again.

- Bussy-Rabutin was one of the three great epistolarians of French literature, Madame de Sévigné and Voltaire being the other two whose letters have achieved cult literary status.

So yes, our count may have been a vanity-riddled ne'er-do-well, an independent spirit out of synch with his surroundings, a carefree and vain braggart and seductor, and, certainly by today's standards, a sexual offender.

But what cannot be disputed are his military skill, his lethal turn of phrase, and his devastating and caustic sense of humour: a man larger than life.

As is the case for most châteaux, this one is out in the countryside and best reached by car from either Dijon (half an hour away) or Paris. The nearest TGV station is in Montbard but you'll still need a car to get to the castle. Ideally, you'll make this stop as part of a one-day tour of the Auxois, the perfect day trip from Dijon.

You might also like these stories!

Did you enjoy this article? I'd love if you shared it!