Fascinated by Gallo-Roman history? Click Here to download > > > Here are 6 ways Rome affected France

- Home ›

- Destinations ›

- Walled Cities in France

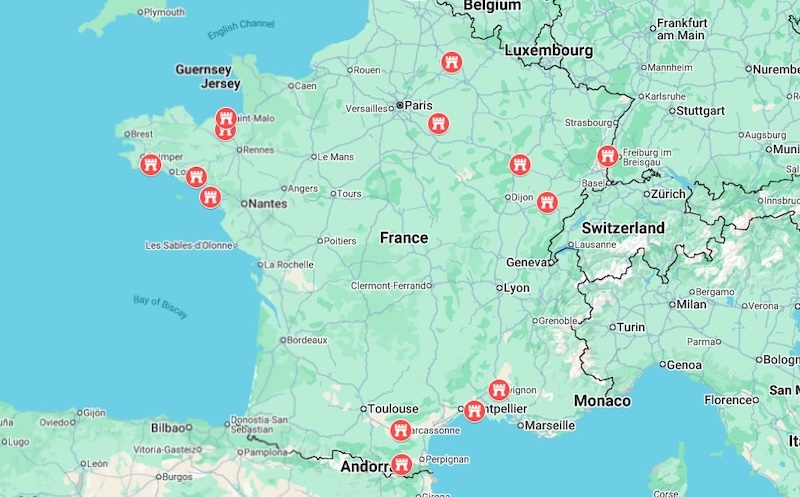

Explore 14 of the Best-Preserved Walled Cities in France

Published 06 August 2025 by Leyla Alyanak — Parisian by birth, Lyonnaise by adoption, historian by passion

Walled medieval French cities were built for defense and control in turbulent times. Some guarded borders, others protected trade or projected power.

This article explores 14 of these, each with its own purpose and legacy.

At times it can be overpowering to step into a town in France and walk along stone ramparts that have stood for a thousand years...

Maybe it’s the sense of protection provided by these massive walls, or the sound of footsteps on cobblestones, or the way narrow lanes dart out like secrets from the walls.

For me, it’s knowing these fortifications have seen so many invasions, revolutions, sieges, or surrenders — all of history, in other words.

In the Middle Ages, France wasn’t a unified country but a patchwork of rival fiefdoms, often at war with one another. Add in external conflicts like the Hundred Years' War, and towns needed serious defenses. Walls were essential for survival.

They also projected power and told observers, "We matter".

Today, many of these once-defensive structures are still standing and exploring them can feel like walking through a living museum. France is home to some of the most atmospheric walled cities in Europe, and while many walls were torn down in peacetime, many also survived.

- 1. Aigues-Mortes (Occitanie)

- 2. Avignon (Provence)

- 3. Besançon (Bourgogne-Franche-Comté)

- 4. Carcassonne (Occitanie)

- 5. Concarneau (Brittany)

- 6. Dinan (Brittany)

- 7. Guérande (Brittany)

- 8. Langres (Grand Est)

- 9. Laon (Hauts-de-France)

- 10. Neuf-Brisach (Grand Est)

- 11. Provins (Île-de-France)

- 12. Saint-Malo (Brittany)

- 13. Vannes (Brittany)

- 14. Villefranche-de-Conflent (Occitanie)

Why are there so many walled cities in France?

14 Fortified cities in France

France must have thousands of fortified villages, towns and cities, and I seem to be developing a weakness for medieval military architecture. Ramparts and fortresses are visually striking, and some are so intricate and sophisticated it's hard to believe they were built so many centuries ago.

Here are 14 remarkable ones.

1. Aigues-Mortes (Occitanie)

The perfectly straight walls enclosing Aigues-Mortes, and to the left, the pink lagoon (OT – aigues-mortes)

The perfectly straight walls enclosing Aigues-Mortes, and to the left, the pink lagoon (OT – aigues-mortes)Aigues Mortes is special for several reasons. It is one of those fully enclosed French medieval towns, with perfect ramparts, and in summer, its salt marshes turn bright pink due to Dunaliella salina algae, a surreal backdrop that draws not only curious travelers (sometimes too many!) but also flocks of flamingoes.

It also happens to be the oldest walled city in France.

Built by Louis IX (Saint Louis) in the 13th century as a Crusader port, it's not hard to imagine him calling for workers to speed up as he prepared to head to the Orient.

It's a bit hard to visualize now but this inland town was once a port, before the coastline silted up and left it landlocked.

The thick square towers and arrow slits aren't decoration: the Tour Carbonnière and Tour Constance were two of the six towers and ten gates built to defend the town, and they’ve never fallen (nor, in honesty, have they been seriously besieged).

The perfectly straight streets inside the walls were designed to let troops march quickly, or they might have made invasion easy if attackers breached the walls. We'll never know.

Today, the former Mediterranean gateway and toll station is a much-loved tourist destination city in southern France, filled with shops and restaurants and cafés, and surrounded by ramparts from which you can gaze at the wetlands of the Camargue (which you should definitely get out and explore).

2. Avignon (Provence)

Avignon ramparts

Avignon rampartsMost people associate Avignon with the Pope’s Palace, but it’s the ramparts that first protected the papal court when it moved here in the 14th century.

The Avignon city walls are as old as the Romans, a first-century build typical of the era. No one is certain of the exact location of the original walls but the perimeter was definitely expanded over time.

With the arrival of the Popes, the city grew and spilled over the walls, requiring new ramparts. These not only protected the palace, but held off floods from the mighty Rhône river.

The walls were funded by taxing salt and wine, and if you look closely, you’ll still see the initials of some 450 medieval stone carvers etched into the upper stones. (They were at one point thought to be Masonic symbols but no, they were simply initials and drawings of work instruments.)

Stretching for 4.3 kilometers, these ramparts, now protected by UNESCO, still encircle the old city, pierced by seven gates. Inside, you’ll find the Palais des Papes (more fortress than palace) and a cluster of medieval streets.

During the 19th century, Avignon almost lost its ramparts when an anti-medieval movement wanted to clean up the city and level some of its less attractive parts. But that was also the beginning of a movement to conserve national monuments, so in the end the ramparts were saved.

After you've visited the Palais des Papes, you can stroll along large sections of the wall, beginning at the famous Pont d’Avignon (Avignon Bridge) and winding your way to the leafy Rocher des Doms gardens, with a view over the Rhône.

3. Besançon (Bourgogne-Franche-Comté)

You can see Besançon's fortifications in the foreground on the left (photo by Marc Perrey)

You can see Besançon's fortifications in the foreground on the left (photo by Marc Perrey)Besançon may be off the beaten track for tourists, but it occupied a spot so strategic it was fought over for centuries, with its first walls erected under Roman rule.

But it wasn’t until Louis XIV captured the town from the Spanish in 1674 that the site reached its full military potential.

Besançon became French, and the king wasted no time appointing his star military engineer, Vauban, to transform the city into a cornerstone of France’s eastern defense. He not only wanted to assert his control, but this region bordered the Holy Roman Empire and the king wanted a visible symbol of French authority.

Begun under Spanish rule, the fortifications were reimagined and completed by Vauban between 1678 and 1711. The result is a stunning citadel that sits 100 meters above the city, and it's easy to see how the fortifications followed the lay of the land.

The Citadel was never tested in battle post-Vauban, as is the case with many of his constructions, possibly because they appeared too impregnable for anyone to really try.

Today, the entire ensemble, along with 11 other Vauban sites or French walled towns, is protected by UNESCO. (If you'd like to read more about this engineering genius, see my post on Vauban on my Substack.)

The Citadel now houses several museums, including a Resistance and Deportation Museum, a natural history museum, and even a small zoo. The ramparts offer sweeping views over the city, the Doubs valley, and the Jura hills beyond.

4. Carcassonne (Occitanie)

Carcassonne is a city in SW France, one of those cities that conjure up fairy tales, with moody cobblestone streets and centuries-old fortifications. There’s a reason so many authors use it as a backdrop for their novels...

It also happens to be Europe’s largest medieval fortified town, encircled by two rings of ramparts that stretch nearly three kilometers, guarded by 52 towers.

Parts of the fortifications are Roman, and others were added in the 13th century, when France shored up its southern defences during its brutal crusade against the Cathars and rising tensions with Spain.

These weren’t symbolic walls. With such innovations as double defenses, they reflected cutting-edge military strategy. Invaders who breached the first wall found themselves trapped in the lices, those bare space between the walls, which controlled access. The most famous of these is the twin-towered and very photogenic Porte Narbonnaise, the main entrance we use today to enter the city.

By the 18th century, Carcassonne had lost its military role and it was slowly abandoned, its walls crumbling. It's terrifying to think that the government nearly demolished it in the 1800s, but for the alarm raised by local historian Jean-Pierre Cros-Mayrevieille. Rushing in to save the day was architect Eugène Viollet-le-Duc, known for restoring Notre-Dame and Mont-Saint-Michel.

His 1853 restoration remains controversial. Some call his steep roofs and Gothic touches inventions. But without him, little would remain. The project spanned sixty years and continued long after his death.

Today, this walled city in SW France is a UNESCO World Heritage Site and tourist magnet. It can feel overrun in summer, but walk the ramparts at dawn or dusk, when the shadows stretch and the crowds vanish, and you’ll understand why this place in France has endured for two millennia.

THE LEGEND OF DAME CARCAS

We hear that Charlemagne's army was laying siege to Carcassonne, then in Moorish hands. Princess Carcas had been ruling it since her husband's death, and the siege was now five years old. Famine set in, and the city was on the verge of surrender. But Lady Carcas stepped in, ordering that the city's last pig and bag of wheat be thrown over the ramparts. Charlemagne, now convinced the city had so much food it could spare a pig and feed it with grain, ended the siege. The Princess rang all the bells. In French, "sonne" means "ring bells". She was already called Carcas... hence Carcassonne! But, given that the town's name was already Carcaso, that is a little hard to believe (and as I said in the title... Legend.)

5. Concarneau (Brittany)

Aerial view of Concarneau ©Studio 29

Aerial view of Concarneau ©Studio 29The Ville Close (or “enclosed town”) of Concarneau, a walled city on the coast of France, sits on a fortified island in the harbor of southern Brittany’s most active fishing port.

It is encircled by granite ramparts and once served to defend against English and Spanish attacks. Now, it welcomes travelers with its creperies, cafés and galleries settled behind its thick walls.

Concarneau was first fortified in the 13th century. During the War of the Breton Succession, the English occupied it until Bertrand du Guesclin ousted them in 1373 after three brutal assaults.

Later dukes reinforced the walls, and Vauban himself recommended upgrades to strengthen the town’s strategic position on Brittany’s vulnerable southern coast.

The town's military role faded in the 19th century, and like Carcassonne, it was almost demolished but was saved by a coalition of locals and artists. Their 1899 petition ensured the ramparts would be classified as a Monument Historique, preserving it for generations to come.

You can walk part of the ramparts for views of the harbor and sea, or wander cobbled streets lined with boutiques and ice cream shops, a cool welcome in the summer heat.

6. Dinan (Brittany)

Dinan's three-kilometer ramparts, the longest and most complete in Brittany, are lined with ten towers and four monumental gates which once controlled movement between Normandy and the Breton coast.

A Benedictine priory emerged here in the 11th century, and in 1064 the town’s castle was besieged by William the Conqueror, an event captured on the Bayeux Tapestry.

The walls we have today are older, and date from the 13th and 14th centuries, when Duke Jean le Roux encircled half the town in stone. Dinan held firm during the Breton War of Succession in 1357, when Bertrand du Guesclin, fighting for the Duke of Brittany, famously defeated Thomas of Canterbury in single combat.

As Brittany slowly lost its independence, Dinan was absorbed into the expanding French kingdom without resistance. It stayed prosperous from trade via the Rance but inside the walls, cloisters and convents replaced garrisons.

Heading down to the port in Dinan

Heading down to the port in DinanToday, visitors can brave the steep, cobbled Rue du Jerzual down to the harbor below, or walk the ramparts past the Tour du Connétable and Tour de Beaumanoir. Every two years, the Fête des Remparts turns the town into a medieval spectacle with pageantry that echoes its defiant past.

7. Guérande (Brittany)

Located near the Atlantic coast in Loire-Atlantique, Guérande is an exceptionally preserved medieval fortified city in NW France and a rare example of a town whose entire medieval wall still stands almost intact.

The ramparts date from the 14th century (seems like the favorite century for ramparts!) when Guérande flourished under the Duchy of Brittany. The town’s wealth came from salt, the prized white gold harvested from the surrounding salt marshes, the marais salants.

But Guérande was both a key trading hub and religious center, so it needed protection. It built a 1.4-kilometer defensive wall pierced by four monumental gates and six towers.

The entrance to the town is through the Porte Saint-Michel, a twin-towered gatehouse with a drawbridge. Inside are the requisite and lovely narrow streets and stone houses (some turned into shops and excellent creperies), all laid out much as they in medieval times. You can walk sections of the ramparts today.

The ramparts of Guerande, in Brittany ©OffbeatFrance

The ramparts of Guerande, in Brittany ©OffbeatFranceOn market day, locals buy cheese and sausage beneath the towers. Meanwhile, just outside the walls, salt workers still rake the same marshes that built the town’s fortunes.

8. Langres (Grand Est)

Perched high on a limestone ridge above the Marne valley, this eastern French town has watched over the landscape for more than two millennia.

Its ramparts, stretching for 3.5 kilometers, are among the most complete defensive circuits in France. Twelve towers and seven gates mark the wall walk – chemin de ronde – from which you'll get sweeping views across the countryside.

An autumn day along the ramparts of Langres, in the Haute-Marne department ©OffbeatFrance

An autumn day along the ramparts of Langres, in the Haute-Marne department ©OffbeatFranceThe earliest stones of the walls were laid by the Romans, whose castrum (military camp) defended the frontier of their empire.

In the Middle Ages, the town grew wealthy and stronger under the powerful bishops of Langres. After a visit in 1688, Vauban added his own touch (of course he did) and modernized the fortifications to survive cannon fire and sieges.

Today, Langres is a tranquil town, often known for its chilly winters or as the home town of philosopher Denis Diderot, whose knowledge is on display at the Maison des Lumières, an excellent museum of the Enlightenment. It makes for a delightful exploration, its streets lined with Renaissance and classical mansions and secret courtyards.

Langres may not be a famous walled city in France – like Carcassonne or Saint-Malo, for example – but it is utterly authentic and quietly beautiful.

9. Laon (Hauts-de-France)

Laon rises above the Picardy plain, encircled by seven kilometers of ramparts that once made it one of the most secure medieval French towns in northern France.

Its hilltop position gave it strategic importance for centuries. Evidence of human settlement goes back to antiquity, and Laon later became a royal city under the Carolingians.

By the 12th century, the upper town was surrounded by walls, gates and towers, eventually reaching 46 towers and 18 fortified entrances. The defenses were upgraded over time, and in the 17th century, a star-shaped citadel inspired by Vauban's designs was added to reinforce the city against modern artillery.

Much of the original structure has disappeared, but a dozen towers still stand, so you can trace the outline of a town that was built to resist siege.

But Laon isn’t just about fortifications. Its cathedral is one of the earliest Gothic churches in France, built before Notre-Dame de Paris.

Notre-Dame de Laon, above the city's ramparts

Notre-Dame de Laon, above the city's rampartsSeveral kings ruled from here, including Charlemagne’s father, and the town played a key role in early French history, changing hands more than once. It even had a brief stint as the kingdom’s capital.

Today, Laon is a quiet town. You can walk along the old walls, visit the Porte d’Ardon, or go down into the underground passages that run beneath the upper town. But you might just settle for the view from the ramparts that stretch far across the plain...

10. Neuf-Brisach (Grand Est)

Neuf-Brisach is a walled city that is different from most of the others we're looking at here.

Built in 1699 on the orders of Louis XIV, it wasn’t adapted from an older town – it was designed from scratch, drawn by Vauban to replace the lost fortress of Breisach across the Rhine. France had been forced to return the fortress to the Holy Roman Empire after the Treaty of Ryswick two years earlier.

With its octagonal walls and perfect interior grid, it remains one of the most complete examples of early modern military planning in Europe.

You couldn't write a better textbook on fortifications: a double ring of bastions and moats surrounds 48 symmetrical blocks, every street radiating with geometric precision from the central parade ground. Everything — the barracks, the church, the mairie — was positioned on purpose.

The snowflake-shaped town of Neuf-Brisach, created by Vauban, military engineer under Louis XIV. Photo ©Luftfahrer, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

The snowflake-shaped town of Neuf-Brisach, created by Vauban, military engineer under Louis XIV. Photo ©Luftfahrer, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia CommonsNeuf-Brisach might have been built for war but it didn't see much action. Still, its defenses were tested.

In 1814 during the Napoleonic wars, it was besieged by Austrian troops and eventually surrendered. The same happened in 1870, when Prussian artillery broke through during the Franco-Prussian War.

Once Alsace was annexed by Germany, the fortifications were reinforced by Prussian engineers. Some of these are still visible, and remained in military use even after the region returned to France. It continued as a garrison town until 1992.

Today, the ramparts are still walkable, a blue line guiding you past firing platforms and defensive outworks.

From above, the town looks like a snowflake stamped onto the Alsatian plain. The interior is calm and orderly, quieter than its dramatic walls suggest.

This is not where you'll find medieval romance, but you will find incredible symmetry and extraordinary planning.

11. Provins (Île-de-France)

Once a star in the crown of the Counts of Champagne, the medieval walled city of Provins is less than 90 minutes from Paris. It flourished as a major trading hub during the 12th and 13th centuries, with some of the largest fairs in Europe.

To protect this prosperity (and probably to show it off a little) the town surrounded itself with nearly five kilometers of stone walls, of which more than a quarter remain today. The towers that dot the wall once served as defensive bastions and watch posts.

You can walk along the chemin de ronde, where hooves once clattered and you could hear the rustle of silk from merchants' stalls below.

The walls were never tested by invasion, but like many of these towns, fortunes waned as trade routes shifted and royal power became increasingly centralized.

Medieval ramparts of Provins

Medieval ramparts of ProvinsOverlooking the upper town is the Tour César, an imposing 12th-century keep named not for Julius Caesar (who never set foot here) but for its formidable Romanesque aura. It was once a prison and a bell tower, and you can climb up for a view across the tiled rooftops and undulating countryside.

Nearby, the Grange aux Dîmes, or "tithe barn", gives you an idea of the town's mercantile past. Its vaulted halls are now a museum that showcases the trades and taxes that once made Provins rich.

But Provins still has a flair for spectacle: every June, it revives its medieval spirit with the Fêtes Médiévales, a two-day celebration with troubadours, knights, falconry, and reenactments within the old city walls.

12. Saint-Malo (Brittany)

Approaching Saint-Malo by boat — whether on a ferry, sailing trip, or even one of the local excursions — gives you a dramatic view of the city’s granite walls rising directly from the water.

Its ramparts shaped like a ship’s hull and built to withstand both enemy cannon and Atlantic storms. Once a stronghold for corsairs, the town thrived on privateering, with royal licenses allowing its sailors to plunder foreign ships, a bit like Saint-Jean-de-Luz further south along the coast.

The wealth poured in, funding mansions behind the walls and fueling Saint-Malo’s fierce independence. In the 16th century, it even declared itself a republic (in name only), loyal to no king but its own.

Much of the city was destroyed in 1944 by American shelling and bombing aimed at dislodging German troops, but the ramparts were spared and the town was rebuilt stone by stone, a near-perfect replica of the medieval original.

Today, you can walk the full loop of the ramparts and at low tide, sandbanks and causeways appear, linking the mainland to offshore forts and rocky islets like Grand Bé, where writer Chateaubriand is buried.

Within the walls, the air carries the scent of crêperies and salted caramel, and you can stop and sample oysters along the way. It's easy to walk around the compact old town, and very atmospheric, almost as though these stones had been standing for centuries, not decades.

13. Vannes (Brittany)

The fortifications of Vannes in Brittany ©A. Lamoureux. Office de tourisme Golfe du Morbihan Vannes Tourisme

The fortifications of Vannes in Brittany ©A. Lamoureux. Office de tourisme Golfe du Morbihan Vannes TourismeSet on the Gulf of Morbihan, Vannes was once one of Brittany’s most important strongholds, guarding inland trade routes and serving as a key port for the Duchy of Brittany.

Its ramparts, begun in Roman times and expanded through the Middle Ages, still encircle much of the old town, their towers casting shadows on the half-timbered houses below.

Most of what we see today dates from the 13th to 17th centuries, including the striking Tour du Connétable and the ornate gates that pierce the walls.

At the height of its power, Vannes controlled access to both the sea and the hinterland, and its defenses were repeatedly tested during the Wars of the Breton Succession and later, during the struggles that led to Brittany’s union with France.

Yet despite this martial past, Vannes feels less forbidding than many other walled towns in France. Its fortifications curve gently through the city, sheltering the former moats of the Jardins des Remparts. From here, cobbled lanes lead into the old town, with its crooked façades and café terraces.

Today, follow the scenic walking route around the ramparts to taste both the present and the past.

14. Villefranche-de-Conflent (Occitanie)

Tucked into a narrow valley where the Pyrenees converge, Villefranche-de-Conflent once guarded the southern frontier of France. Founded in the 11th century, it was later refortified by Vauban in the late 1600s, who doubled the pink marble ramparts and added Fort Libéria above — a citadel cut into the mountain and connected to the town by a 734-step tunnel carved through the rock.

Inside, a single main street runs the length of town, lined with stone façades, artisan workshops, and the occasional creperie. It’s compact, walkable, and largely unchanged in scale since the 17th century.

You can climb the ramparts, visit the old town hall, or ride the tourist train up to Fort Libéria, a steep ascent, but worth it for the views.

Nearby, the Grandes Canalettes caves offer an unexpected detour underground, with dramatic rock formations just minutes from the medieval gate.

Stay overnight and you’ll have it almost to yourself.

Why are there so many medieval walled cities in France?

Fortified cities are a cornerstone of France's history and are a reflection of centuries of conflict and power struggles.

What we now call France was once a fragmented patchwork of regions, each with its own lord or duke, making walled cities essential for defence. Each of these regions needed protection against one another, or against foreign invasions or peasant uprisings, and these fortified towns were essential

Geography made things worse. France’s central position in Europe exposed it to repeated conflict, especially along its northern and western frontiers.

Brittany, for instance, remained semi-independent for centuries and saw constant skirmishes with English, Norman, and later French forces.

Walls were built not just for protection, but also to assert power. Today, having a huge wall around your property usually means you have something to protect, and that you're rich and powerful.

This was also the case for towns in the Middle Ages.

A city encircled by stone screamed strength and wealth. It meant control of trade routes, or perhaps royal favor. Walls meant status.

Over time, many fortifications were dismantled. In peacetime, they stood in the way of urban growth, and without any external threats, they weren't needed anymore. In many cases, people simply walked off with the stones, using them for their own building projects.

Today, walled towns and their ramparts don't really serve a purpose, but they do contain centuries of lore and connect us to our history and society.

IF YOU NEED TO RENT A CAR IN FRANCE

Don't wait until the last minute, especially if you want one of the scarcer automatics.

🚗 Check availability at Discover Cars (it's what I use to compare prices).

French walled cities you can sleep inside

Some walled cities feel like open-air museums during the day but come alive in a different way after dark.

Staying within the ramparts lets you step out into cobbled silence once the day-trippers leave and the lanterns flicker on.

Here are a few where that’s still possible:

- Carcassonne – The ultimate medieval experience. Several hotels are located within the citadel itself, including Hôtel de la Cité, which offers turret views and evening strolls beneath floodlit walls. Rooms book up quickly, especially in summer.

- Aigues-Mortes – This compact, square-shaped town is almost entirely walkable in 10 minutes — but spending the night inside the ramparts means you’ll have it mostly to yourself in the quiet morning light. Guesthouses and boutique hotels abound, many in converted medieval buildings.

- Saint-Malo – Choose a hotel intra-muros (within the walls) for a front-row seat to the tides and sunsets. Wake up to the sound of gulls and the scent of sea air drifting through the city gates. Have a look at the Hôtel France et Chateaubriand and Hôtel des Abers.

- Dinan – You’ll find plenty of atmospheric B&Bs tucked into old stone houses in the upper town. Staying inside lets you explore the ramparts at sunrise or enjoy the Jerzual steps without the crowds.

- Langres – Less touristy but surprisingly well-equipped, with several small hotels and guesthouses right inside the walls. The atmosphere is hushed, especially in the evening when the streetlights cast long shadows on the ramparts. I admit I loved the Hotel de la Poste, reputed to be France's oldest.

- Provins – A few guesthouses exist within the upper town, including historic manors and converted farmhouses. It’s a quieter option, especially if you visit outside of festival weekends. Check out the Hotel des Vieux Remparts.

Walled cities you can reach by train

Not all walled cities require a car. A surprising number are connected to the rail network — some via high-speed TGV, others through slower regional lines.

Here are the ones easiest to reach:

- Avignon – Served by both TGV (Avignon TGV station) and TER (Avignon Centre), this is one of the most accessible walled cities in France. The ramparts begin just a few steps from the station.

- Carcassonne – On the main Toulouse-Narbonne line, with direct trains from both cities. The station is within walking distance of the lower town and about 25 minutes’ walk (or a quick shuttle) to the Cité.

- Provins – A direct regional train from Paris Gare de l’Est takes just over 90 minutes. It’s one of the best medieval cities in France to visit on a Paris day trip.

- Laon – Reachable via TER from Paris Gare du Nord in under two hours. From the station, you can walk or take the funicular to the walled upper town.

- Langres – More of a detour, but doable. Take a TER to Langres-ville, then catch a shuttle or taxi to the historic center atop the hill.

- Saint-Malo – Direct trains from Rennes in under an hour. Rennes itself is well connected by TGV to Paris. The old town is a 10-minute walk from the station.

You can book all your train tickets here.

For Concarneau, Dinan, Neuf-Brisach, Villefranche-de-Conflent, and Aigues-Mortes, a car is either essential or highly recommended. Regional bus routes may exist, but schedules are infrequent and not always visitor-friendly.

Before you go...

Exploring the many walled cities in France by walking along their ramparts usually offers fabulous scenic views but also gives us a glimpse into the country’s past and the ingenuity that went into protecting it.

If you're drawn to the drama of high walls and hidden passages, you might also enjoy these hilltop villages of the Luberon, many of which grew from the same need for defence and independence.

And if you're keen on even more walled cities and town, wherever they are, here's a list of walled cities in France – and beyond.

FAQ

Was Paris ever a walled city?

Was Paris ever a walled city?

Yes, Paris was a walled city for centuries, with successive fortifications marking its growth. From the Roman wall on the Île de la Cité to Philippe Auguste’s medieval ramparts, Charles V’s expansions, and finally the vast 19th-century Thiers Wall, each was eventually outgrown. Today, fragments remain in places like the Marais and the Louvre, while the Boulevard Périphérique still traces the line of the last wall.

Do any European cities still have their city walls from medieval times?

Do any European cities still have their city walls from medieval times?

Yes they do. In addition to those in France, like Carcassonne or Aigues-Mortes, you'll find largely intact medieval walls in Ávila (Spain), Dubrovnik (Croatia), York (England), Tallinn (Estonia), and Rhodes (Greece).

Did you enjoy this article? I'd love if you shared it!