Fascinated by Gallo-Roman history? Click Here to download > > > Here are 6 ways Rome affected France

- Home ›

- Ze French ›

- La Gastronomie ›

- The French Baguette

Essential French Baguette Facts Every Connoisseur Should Know

Updated 26 March 2025 by Leyla Alyanak — Parisian by birth, Lyonnaise by adoption, historian by passion

Like most Frenchwomen, I buy my baguette every day, a reflex action I don't think about. But I was fascinated to find out its history, the different kinds of baguette, and the etiquette supposedly involved in eating it.

The standard baguette as we know it is probably not much more than 200 years old, even though a few pale imitations did exist a bit earlier.

However recent, it has become one of the most iconic foods of France, as ubiquitous as Bonjour, one of the first French words people learn.

Let's see what other French baguette facts we can unearth!

NOTE: Pages on this site may contain affiliate links, which support this site. See full Privacy Policy here.

Hungry yet?

Hungry yet?Basic French baguette facts you need to know

Whatever the statistics, they all converge on one thing: the utter magnitude of the French baguette habit.

- Each French person eats around 160 grams of baguette a day (I can vouch for that)

- Every second, 320 baguettes are consumed in France

- French people eat 32 million baguettes a day (population 70 million)

- We eat six billion baguettes in France each year, or nearly 100 per person per year

Sound like a lot?

It's a lot less than we used to.

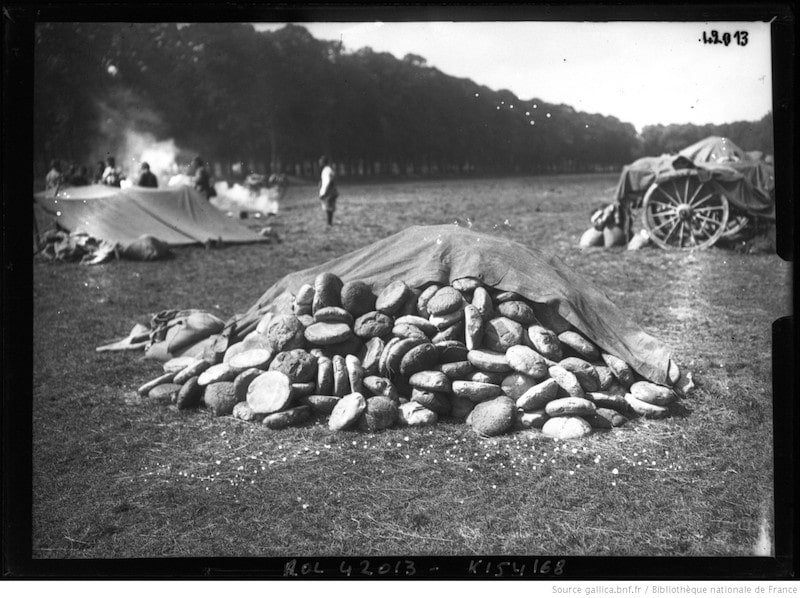

Back in the 18th century, in Marie-Antoinette's time, bread was the main food of 90% of the population and we ate, on average, about 1 kilo of bread a day (to demonstrate my impeccable mathematical skills, that's about six times what we eat today).

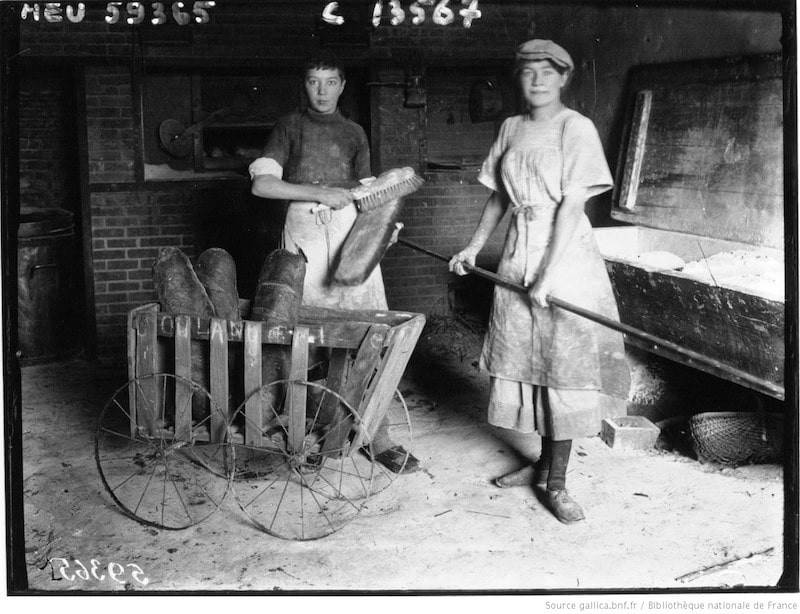

This was the typical round bread that was the basis of the French diet. Here, we see a mound of round bread, the standard military ration, in Amiens, during World War I

This was the typical round bread that was the basis of the French diet. Here, we see a mound of round bread, the standard military ration, in Amiens, during World War IKeen to try a food tour while you're in Paris? Take your pick!

So what is the difference between French bread and "une baguette"?

There are many kinds of French bread, which is the generic term for breads made in France: a baguette, therefore, is a type of French bread.

But a baguette isn't just any old oblong piece of bread. Like most things French, it has specific characteristics, regulated by law, and can be defined.

INTERESTING FACTS ABOUT THE DIFFERENT KINDS OF BAGUETTE

The basic regular baguette usually weighs about 250g and is 55-80cm long. There are variations, however. You can buy a flute at 200g, or an even smaller ficelle (ficelle means string) at 120g. You can also get larger ones: by the time it weighs 300g, it is called a pain traditionnel, or traditional bread (500 grams is just over 1lb and 50cm = 1.5 ft).

These are strict guidelines. Deviate, and you no longer have a baguette.

(What is a baguette in English? A wand.

And baguette pronunciation? Bag-ETT.)

You can buy it well-baked and crusty (bien cuite) or less so (pas trop cuite).

And what do you put in a French baguette? Anything you want. Or... nothing at all.

THE ULTIMATE GUIDE TO FRENCH BREAD

In Good Bread is Back, historian Steven Laurence Kaplan talks about the comeback of good French bread and tells you pretty much everything you need to know about the baguette and other French breads. Buy it here on Amazon

- At breakfast, it is used as a 'tartine': you split it open lengthwise and add butter and/or jam; you can then either eat it as is or dunk it into a bowl of café au lait.

- At lunch, you'll see people munching on a jambon-beurre (a baguette with butter and ham and possibly a tiny pickle or two), a ham and cheese baguette, or one of the many new fillings ranging from chicken curry to brie and honey.

- At dinner, your baguette will be used throughout the meal as an accompaniment, as well as alongside the cheese course. There's nothing snooty about a cheese course, by the way – even the most proletarian of eateries will give you a choice between cheese and dessert.

“The French don't snack. They will tear off the end of a fresh baguette (which, if it's warm, it's practically impossible to resist) and eat it as they leave the boulangerie.

—Peter Mayle

The baguette in France has become such an icon of French culture that there is even a Grand Prix of the 'baguette tradition', launched in 1994, in which Parisian bakers of bread bake their best loaves for a panel of judges.

There is a hefty money prize (€4000, which at the time of writing is about USD 4700) but even more prestigious is the contract to supply the President's bread for a year on a daily basis.

Is perhaps the Parisian baguette better than all others?

Of course not, and a newer contest now judges baguettes throughout the country. An initial triage takes place by region, and each regional winner then competes nationally.

And the accession of the humble baguette to UNESCO's Intangible World Heritage list in November 2022 cements its status once and for all – not as a food in itself, but for the tradition that has gone into making it, a welcome development in the face of creeping industrial competition.

One more thing you should know...

Many bakeries have their own baguette specialities, which may explain why some small towns have far more bakeries than you might expect for their size.

My nearest town (of about 2000 people) has three bakeries (the fourth one, which had the best artisanal baguettes, closed down after a fire).

One of the bakeries is industrial and its bread tastes predictably stale, so we can write that one off right away. But the baguettes in the other two are equally delicious.

So what sets them apart?

The specialty baguettes: one has a baguette with sesame and poppy seeds, and the other has two separate types - sesame baguette and poppy baguette. So you see, sometimes the differences are infinitesimal.

The origin of the baguette

However recent it may be, we simply cannot pinpoint the baguette's origins. As a result, plenty of stories have emerged claiming its birth and since we can't confirm any of them, go ahead, choose the one you like best.

The earliest story attributes the baguette to Napoleon (and we all like a good Napoleon story). French bread used to come in roundish loaves (the cakes, remember?).

These were too cumbersome for soldiers to carry so Napoleon decreed a change in shape: henceforth, soldiers should be able to carry their bread more easily in their back pocket (must have been a large one).

A tempting story, but unlikely.

Napoleon in battle, and not a baguette in sight among the soldiers (Photo Antoine-Jean Gros, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons)

Napoleon in battle, and not a baguette in sight among the soldiers (Photo Antoine-Jean Gros, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons)The next story places the baguette's origin in... Vienna, not Paris (we don't like this one much).

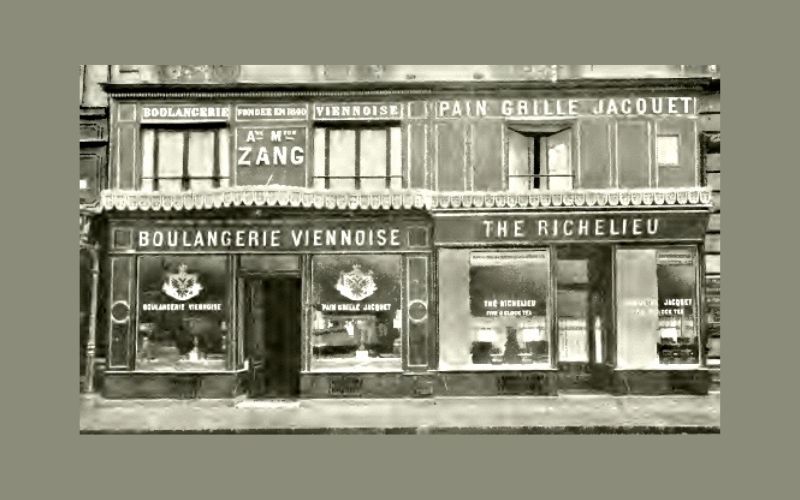

Viennese bread was introduced to Paris in 1830 and became widely popular. It included the kipferl, a crescent-shaped pastry believed to be the ancestor of the croissant.

A few years later, an Austrian officer, Auguste Zang, opened a bakery in Paris and imported the first steam oven, making for crustier bread. He may have imported the idea of the baguette from Vienna, or he might have invented it right then and there, making our venerable symbol a bit... less French.

Or, he might have had nothing to do with it at all.

The original bakery where Auguste Zang may perhaps have invented the baguette, at 92 rue de Richelieu in Paris

The original bakery where Auguste Zang may perhaps have invented the baguette, at 92 rue de Richelieu in ParisYet another tale places the birth of baguette bread in the early 20th century, during the construction of the Paris métro, or subway.

Knife fights often broke out among workers, the same knives they carried to cut their roundish loaves of bread. In this version, the so-called 'father of the métro', engineer Fulgence Bienvenüe, asked a baker to develop a type of bread that could be broken without a knife, and presto, the baguette was born.

(You may have heard that a baguette should never be cut with a knife: this is partly etiquette, and possibly in part based on this metro legend.)

And yet another story: A new law in 1919 forbade work before 4am. Since the baguette needed less time to rise than other breads, it would have quickly become popular among bakers.

The two more recent stories seem highly unlikely. While a long loaf of bread may have been spotted as far back as the 17th century at the court of Louis XIV, the baguette as we more or less know it today already existed under Napoleon III, who ruled from 1852-1870, well before the metro was built or sensible labour laws passed.

Madeleine Danniau, a baker in Exoudun, in western France, baking bread during World War I - while much bread was round, plenty of longer loaves like these were also baked

Madeleine Danniau, a baker in Exoudun, in western France, baking bread during World War I - while much bread was round, plenty of longer loaves like these were also bakedIn the end, the baguette may have developed naturally. After all, the more crisp crust the better, right?

How to eat baguette (or, the secrets of baguette etiquette)

Here are a few basic socially acceptable rules that apply to the baguette.

- You don't cut it with your knife but use your fingers to tear off pieces as you need them, one at a time (not all at once!)

- The first bit of baguette is usually eaten once the first course arrives at your table, not before.

- You don't dip your piece of baguette (or any bread) into your sauce with your fingers. You can spear it with your fork if you really want to absorb that sauce, but fingers? No-no.

- You don't slather butter over your baguette. If you must have butter, you can put a pat on a small piece of bread, but not on a slice. No sandwiches!

Are you planning on baking your own baguettes? If you are, you may need this carbon steel pan to bake four at a time!

How to store baguette

Even though you have to eat your baguette within a day or so, there are times when you'll face an unfinished baguette. What to do?

- wrap the pieces in cloth or paper, and keep them in your breadbox

- do the same thing and pop them in your freezer

- don't wrap the bread in plastic – it needs to breathe

If you've kept your leftover baguette in a breadbox, you'll have to warm it up for it to regain some freshness. You can reheat yesterday's baguette in a hot oven. First, spray your baguette with water, wrap it in foil, and put it on the oven rack.

If it's frozen, you'll want to know how to defrost or reheat a frozen baguette. I should warn you, though, nothing you can do will make it as fresh as it was when you bought it. Still, it's perfectly salvageable:

- you can thaw it and then heat it in the oven, but the crust will be limp

- better yet, wrap it in foil, place it in a medium-hot oven, and let it thaw as it warms up

Here are ideas of what you can do with yesterday's baguette.

Beyond the baguette: the history of bread in France

The baguette may have had relatively recent origins but bread itself has long been an actor in France's history.

The Egyptians invented bread, the Greeks developed it and the Romans refined it.

In the Middle Ages, fresh bread became central to French food habits and Charlemagne, King of the Franks, decreed that there should always be enough bakers and that bakeries should be kept clean and ordered.

In 1305, the quality and price of bread was set for the first time and the sale of poor-quality bread – rat infested or rotten – was forbidden. The rich ate white bread and the poor ate it black.

In pre-revolutionary France, the average French person of working class consumed up to 2 pounds of bread per day. It was not a side dish — it was the meal. When bread prices soared due to poor harvests and bad economic policies, people couldn’t eat.

As wheat prices rose and France's monarchy deteriorated, people regularly took to the city streets in protest. In the spring of 1775, after a couple of poor harvests, France underwent the War of the Flours. Speculators pushed up prices by holding onto large stocks, bakeries were emptied and people began to starve.

This is when Queen Marie-Antoinette was (wrongly) believed to have said: "Let them eat cake!" Popular anger was growing.

In the late 1780s, a series of poor harvests (especially in 1788) led to grain shortages and soaring bread prices. In Paris, the price of bread doubled in a single year. People queued for hours, riots broke out, and bread became a rallying cry. The most iconic example? The Women’s March on Versailles in October 1789, driven largely by hunger and the inability to feed their families.

During the Revolution, new laws banned certain types of bread that were seen as symbols of inequality. In 1793, the Convention decreed that bakers could no longer produce luxury loaves just for the wealthy. Instead, they were required to bake a “pain égal” (equal bread) for everyone, an early gesture toward food equality. This didn’t create the baguette, but it laid the ideological foundation for a more democratic loaf.

Although the modern baguette didn’t appear until later, it would embody the revolutionary ideals of simplicity, accessibility, and national identity. It became a symbol of French everyday life, just as bread had been the symbol of inequality a century earlier.

The 'memorable day of Versailles' was a Monday, 5 October 1789. On this day, a mob of armed Parisians left their city and headed towards Versailles, crying: "We need bread, not laws." (gallica.bnf.fr)

The 'memorable day of Versailles' was a Monday, 5 October 1789. On this day, a mob of armed Parisians left their city and headed towards Versailles, crying: "We need bread, not laws." (gallica.bnf.fr)By 1856, the baguette habit was intensifying and Emperor Napoleon III (nephew of the first) decreed its exact measurements: 40cm in length and 300g in weight (that's a bit heavier than today's 250g).

As for the name 'baguette', it seems to have made its first appearance in 1920, in a Paris regulation that codified (and slightly modified) its length, weight and price.

Initially more common in the wealthier quarters of urban areas, the baguette's popularity skyrocketed after World War II, with the end of rationing. And today, apart from the baguette traditionnelle, you'll find versions that diverge widely from the original, using different flours or filled with fruit.

In 1993, the French government issued a decree governing the baguette de tradition française and fixed its acceptable ingredients: wheat flour, yeast and salt, perhaps making the baguette the most regulated hunk of bread in the world.

A baker gets his baguettes ready for baking (RudolfSimon CC BY-SA 3.0)

A baker gets his baguettes ready for baking (RudolfSimon CC BY-SA 3.0)Beyond the traditional baguette

A fresh baguette may be France's most popular bread, but it is not the country's only bread.

There are plenty of round or oblong breads, which often keep better than the French baguette.

Usually, these are named after the flour they use: pain de seigle (rye bread), maïs (corn), millet, avoine (oat) and more.

You'll also find plenty of specialized breads nowadays, bread with lard or with cheese or with raisins. These may be familiar to Anglo-Saxon bread-lovers but they are relatively new to France's hinterland.

In my small village, the bakery only began offering a whole grain baguette a few years ago and now, we are sophisticated, with dark breads, sesame baguettes and the occasional bread with lard or cheese on market days.

Regional breads also exist, which you'll find locally in some parts of France but not in others. A good example is the fougasse in Provence.

Frankly, there's nothing like waking up in the middle of the night for lovers of midnight snacks. A fabulous "jambon-beurre" is easily put together, a quick snack that somehow remains on my bucket list no matter how many times I eat it.

So there is some truth in stereotypes. When you imagine every French person with a baguette under their arm, you will not be far from the truth. But please, leave Marie-Antoinette out of it: she had enough troubles without wishing hunger upon the population.

FAQs about French baguettes

Where in France does baguette come from?

We don't know. Some say the invention of the baguette was designed as a soldier's ration under Napoleon, others say it was invented by a Viennese baker in Paris, and yet others say it was developed more than a century ago as food for Paris metro workers.

What does baguette mean in France? What is a baguette in French?

A baguette is a "wand" or a "stick". You can use baguettes to eat your Chinese meal – des baguettes chinoises – or to wave a rabbit out of a hat, une baguette magique. It's all about the long, thin baguette's shape.

Une baguette is how you say it in French.

How much is a baguette in France?

It varies. As of this writing (April 2022), you would usually pay between €1.10-1.30, but that price could rise quickly as wheat prices soar in the wake of droughts and the war in Ukraine.

How do you eat a baguette?

There aren't many rules – but there are a few. You can break it into pieces, but shouldn't cut it with a knife. Except for breakfast, when you would cut it lengthwise and slather it with butter and jam.

For how long is a baguette considered fresh in France?

No more than eight hours. It's something we buy every fresh every day. But if you can't go out to buy one, you can always toast it or put it in the oven for a few seconds to freshen up a leftover baguette.

How many carbs in a baguette, and how many calories in a baguette?

A standard baguette weighs 250g and contains about 140g of carbs and has 722 calories.

Before you go...

The modest baguette may be one of France's most recognized foods, but this is a country made for the palate, with plenty of variety, and many staples. You can read more about France's most popular favorite foods right here.

Did you enjoy this article? I'd love if you shared it!

You might also like

Pin these and save for later!