Fascinated by Gallo-Roman history? Click Here to download > > > Here are 6 ways Rome affected France

- Home ›

- Destinations ›

- Southern France ›

- Luberon Villages

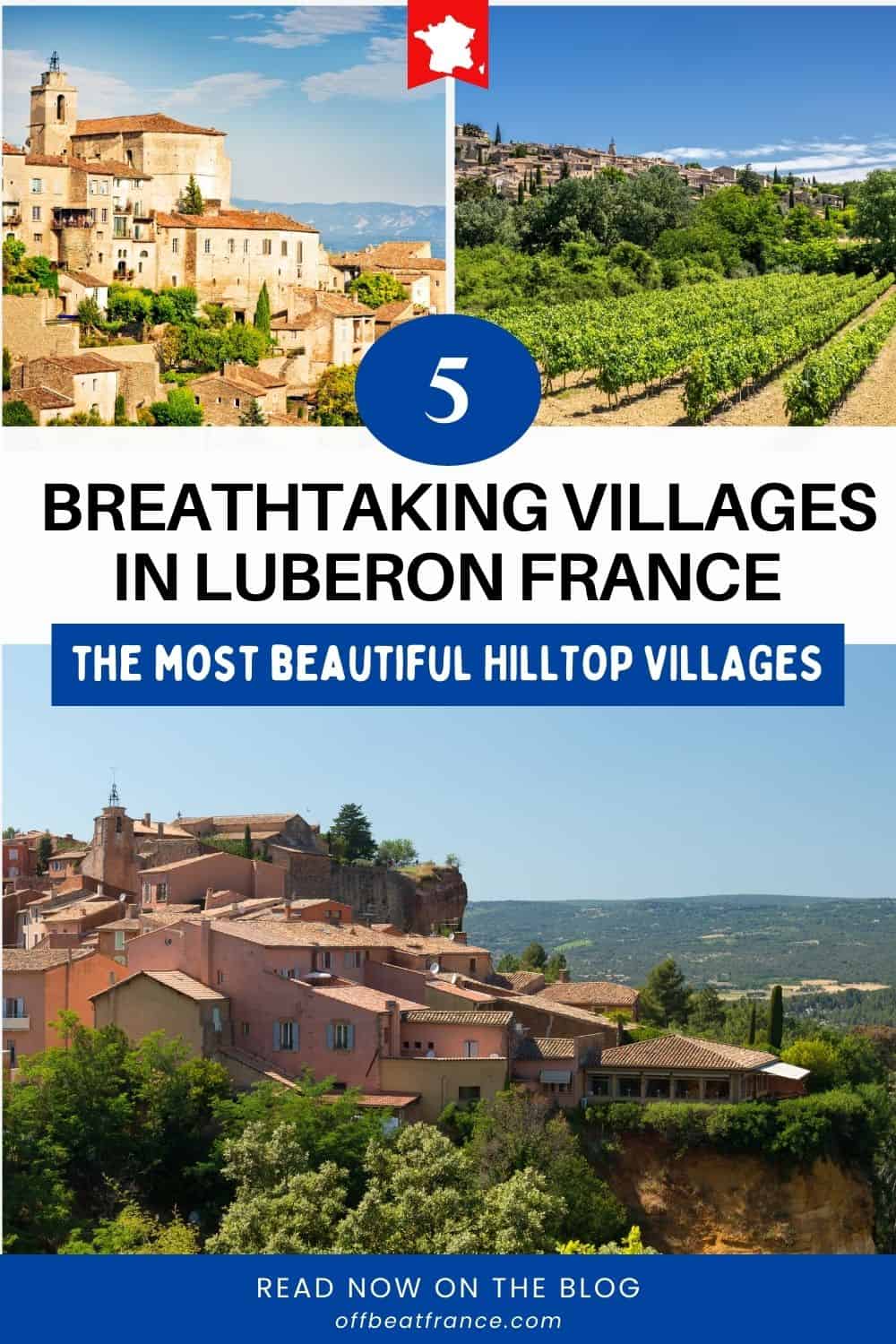

5 Breathtaking Hilltop Villages in Provence's Luberon

Published 8 April 2021 by Leyla Alyanak — Parisian by birth, Lyonnaise by adoption, historian by passion

Villages in Provence always conjure visions for me of isolated hilltops, narrow streets and the scent of lavender. My latest visit to Provence was in winter – only the lavender was missing. But these five villages in the Luberon were just perfect.

There's a certain quality to the villages in Provence, and more so to those of the Luberon, located in the Pre-Alps of central Provence (see the map below). This Provence countryside of lavender and light has long been a magnet for artists and writers and lovers of beauty.

I know I was captivated.

The area is dotted with magnificent villages, some heavily touristed, some virtually untouched (but I suspect it's only a matter of time).

Here, I'm looking at the five most visited - because of their gorgeousness, of course, but also because they happen to carry the prestigious label of most beautiful villages of France. In another life (the one in which I win the national lottery) I would have tried to visit all 176 of these villages scattered across France.

But for this trip, these five will do just fine, thank you. (If you love hilltops, you can also explore fortified towns in other parts of France.)

SUMMARY

These 5 magnificent villages are considered among the Luberon's most beautiful:

- Ansouis, its chateau and authentic streets

- Gordes, viewed from below, its bories and its cobblestones

- Lourmarin and its quirkier vibe

- Ménerbes, popularized by the books of Peter Mayle

- Roussillon and its Ochre Trail

NOTE: Pages on this site may contain affiliate links, which support this site. See full Privacy Policy here.

Sticking to the five "most beautiful" may sound like treachery towards the other delightful hamlets of the Luberon – places like Goult, Bonnieux, Oppède-le-Vieux – but I had to start somewhere.

Three are perched on hills, two are lower down. One is built using the local dry stone technique, another has walls plastered with ochre. Some are crowded with tourists and souvenir shops, others look more authentic and laid back.

To avoid any jealousy, I've listed them in alphabetical order. But, we all have our favorites!

1. Ansouis

Each Luberon village has its personality and one word that would aptly describe Ansouis is "authentic". Perhaps it was because I visited in winter or at a time of few tourists, but deep inside the village, removed from the attractive eateries of the entrance, a certain untouched, ungentrified calm permeates the streets.

Next to a fountain, two art students reproduce a classic scene of shutters and vines, a black and white shepherd dog gazing peacefully as I walk by.

Two of France's most loved films, Jean de Florette and its sequel, Manon des Sources, were partly filmed here, and helped put the Luberon on the map as a tourist destination.

The little square at the entrance to town... a typical view of Luberon France

The little square at the entrance to town... a typical view of Luberon France The serene streets of the Provence village of Ansouis

The serene streets of the Provence village of AnsouisAnsouis is the southernmost of the five and to get here, you'll follow a winding (but spectacular) road through the mountains from the north.

For half an hour, you'll be transported into a landscape so different from the lush lavender fields and rows of olive trees that accompanied you in the north that you may think you've left the Luberon behind... Not so.

The Château d'Ansouis

As is the case in most of these fortified villages, the castle sits at the pinnacle, atop a hill, as it should in order to scan the horizon and repel invaders. It is strategically positioned on the route between Apt and Aix-en-Provence, perfect for defense.

Of course it has all the trappings: a dungeon, four watchtowers and ramparts, but what is most surprising is that it is two castles in one: at its core, a medieval fortress, with a proper Renaissance château built around it a few centuries later. Once inside, you can clearly see where the Middle Ages end and the Renaissance begins.

Ansouis, Provence in springtime, seen from a distance, crowned by its castle ©HOCQUEL A - VPA

Ansouis, Provence in springtime, seen from a distance, crowned by its castle ©HOCQUEL A - VPAThis particular home was built by the powerful Forcalquier family, whose reign over the village lasted until 1178, after which the equally powerful Sabran clan took over.

There's an intriguing story about the early Sabrans: a family scion of the late 13th century, Elzéar, was married young to an equally young lady, Delphine. They fell in love, but were fervent in their faith, so fervent that in 1316 they took a vow of chastity (not great if you are trying to assure your descendancy) in the small village chapel. And so they lived, spending their nights in prayer rather than in connubial bliss.

Not unreasonably, Elzéar's parents worried about the lack of an heir, and assigned servants to spy on the couple. The young pair would feign sleep and pretend to snore, and when the servants would fall asleep, they would rise and begin their night of prayer. Even the best spies reported that although Elzar and Delphine shared a bed, they slept side by side and never once removed their clothes.

When accused of not consuming their marriage, Elzéar replied: "I have a fine and lovely wife and that is more than enough."

Both were evetually canonized as Catholic saints, but what is less clear is how the family line was continued. This entry about their genealogy neglects any reference to descendants... yet the château appears to have stayed in the family.

The years passed, the structure fell into disrepair, and restoration only began in the 1930s. But in 2008, the château was sold off in a messy auction, its heirs unable to agree on their inheritance. The new owners (who are antique collectors) have refurbished the interior lovingly and with authenticity and offer guided tours, which you can book by contacting the castle. The tours, given by the lady of the manor, are in French only.

A Provence must see: Ansouis Chateau close-up HOCQUEL A - VPA

A Provence must see: Ansouis Chateau close-up HOCQUEL A - VPAThe Eglise St Martin

Outside the church: fortress or house of worship?

Outside the church: fortress or house of worship?From the outside, the church looks a bit forbidding, more like a walled fortress than a place of worship. But push the door and the feeling of welcome envelops you.

No one really knows how old it is, but it was probably built in the 12th century, when the village was at its largest.

If you've seen Manon des Sources, you might recognize it as the site of Manon's wedding...

Inside the church of Ansouis

Inside the church of AnsouisThe greatest pleasure to be derived from Ansouis is simply to stroll along its quiet streets. Some of the stone houses are more than 500 years old, and you may forget which century you are in for a moment. Quiet, peaceful, true.

When in Ansouis...

- While visiting the château d’Ansouis, don't forget to admire their French-style gardens.

- If you like these formal gardens, not far from Ansouis you'll find the 17th-century Château de Sannes. Wine tasting or plenty of other things to try, from yoga in the vineyards to country walks with a druid.

- Fancy a Michelin-starred restaurant? Try Olivier Alemany's cuisine at La Closerie.

- Want to find out more about Ansouis? You'll find it here.

- Book your accommodation in Ansouis, one of the loveliest small towns in France.

LUBÉRON TOURS AND TICKETS

➽ Half-day best of the Lubéron from Avignon

➽ Full-day highlights of the Lubéron from Avignon

2. Gordes

You cannot possibly enter Gordes without being utterly charmed.

It has been listed as one of France's favourite villages – there is actually an official competition and television show in which we get to vote! So the town has had its share of camera crews and flashes of fame.

And with good reason.

The first thing you'll notice in Gordes, on arrival, are the long walls of dry stone, an ancestral technique now protected as an intangible asset by UNESCO World Heritage. On and on they stretch, steadfast in their uniformity, as though they had risen from the ground in perfect little lines. I was easily sidetracked by them, almost hypnotized by their patterns.

While stunning up close, the village is just as beautiful from afar. If you're driving here, before you start your climb is a small lay-by: this is the place to stop for "the" iconic photograph.

Gordes, France: The iconic photograph taken from below

Gordes, France: The iconic photograph taken from belowDominating the center of town is the towering Château de Gordes. Already in existence in 1031, it was rebuilt 500 years later during the Renaissance. Mostly uninhabited, its owners used it for storage or as a prison – getting to Gordes on horseback cross-country wasn't quite so simple a few centuries ago.

The château was somewhat roughed up during the French Revolution (what wasn't?) but at least it wasn't destroyed. During World War II, Gordes was an active player in the French Resistance and several hiking paths now commemorate the fighters, known as the maquis.

The village's artisans lived in the lower town (it was known for its weaving and leatherwork), with the nobility on the hill, looking down. Many of the houses are hidden from view, with only a doorway apparent. You'll need a drone to see the turquoise swimming pools or landscaped terraced gardens...

After World War II, Gordes began attracting visitors. Artists moved here, captivated by the picturesque narrow streets but also by the sweeping views over the Provence region. Most famous of these were Marc Chagall and Victor Vasarely.

The narrow alleys of Gordes are a joy to explore. (Please make sure you've got the right walking shoes – this is NOT the time to test your new Italian heels). The most beautiful villages in Luberon are often hilly, as is Gordes, with plenty of bumpy ups and downs. Even the cobblestones have cobblestones: you'll notice that some cobblestone streets have steps going up the center; donkeys used these, their cartwheels crawling alongside on the flatter surfaces.

On market days you'll be able to pick up local produce, but it's also the most crowded day and with parking at a premium, you may wish to choose your battles.

A steaming hot day is the perfect time to visit the underground caves of the Palais St Firmin, a Renaissance palace which went from abandoned to listed as a Historical Monument, and is now a private home. Its tunnels are part of a vast underground network that pierce the mountain below Gordes, seven storeys deep in places. Given the lack of space above ground, the village dug deeper to increase its storage capacity, although many of the town's subterranean passages have yet to be explored or even rediscovered.

In addition to the Château de Gordes and the Palais St Firmin, there's another intriguing site near Gordes: the Village des Bories, built with that same stone technique you will have seen on the way in. These huts were used by seasonal farm workers during the 18th century, abandoned, and eventually rediscovered during the 1950s, overgrown and decrepit. After years of restoration, they are now as pristine as when they were first built.

Le Village des Bories - what used to be a sheep pen

Le Village des Bories - what used to be a sheep penWhen in Gordes...

- Are you a fan of stained glass? If so, you must visit the Musée du Verre et du Vitrail (and don't miss the monumental sculptures of Frédérique Duran in the gardens...)

- Nearby, the Moulin des Bouillons is an ancient olive press which dates back to the 16th century; there has been some kind of press on this site since Antiquity.

- If you cycle, there are wonderful routes throughout the Luberon but especially around Gordes. And if you'd rather take it easier, you can rent an electric bike.

- While you're in Gordes, the iconic Abbaye de Senanque, built in 1220, is nearby. If it's summer, you'll be overwhelmed by the sight of lavender. You can walk here in 45 minutes (or drive in ten).

- Book your accommodation in Gordes, one of the best places to stay in Provence if you're visiting the Luberon.

3. Lourmarin

Be careful when you drive into Lourmarin: the sight of the castle immediately on your right is so breathtaking you might take your eyes off the road for a moment.

Lourmarin Castle, in one of the best Luberon villages

Lourmarin Castle, in one of the best Luberon villagesInterestingly, it would seem that the original "owners" of Lourmarin were the Forcalquier and then the Sabran families, the same ones we first met in Ansouis, but from different branches.

The château is an unusual construction, built in two parts like that of Ansouis: a medieval section from the late 15th century, and in the early 16th, a Renaissance addition.

The castle had fallen into ruin but in 1920 it was bought and restored by a rich merchant and art lover from Lyon, Robert Laurent Vibert. After his death, the castle was turned into a foundation for young artists. Also, it may be haunted...

Inside the restored château of Lourmarin, one of the loveliest places to visit in Provence ©HOCQUEL A - VPA

Inside the restored château of Lourmarin, one of the loveliest places to visit in Provence ©HOCQUEL A - VPAThe narrow gorge which opens up into Lourmarin made things practical for the Romans: they could keep a keen eye out for invaders and protect the village's ever-growing population.

With the ousting of the Romans by the Moors who swept in from Spain, many villages, including this one, would be abandoned, and then rebuilt.

Then, during the 12th century, the village crossed paths with a group of Catholic dissidents, the Vaudois, whom no amount of persecution had been able to stamp out. They had found refuge in what is now northern Italy, eventually joining the Protestant reform movement. A group of these Vaudois were invited to settle in Lourmarin, turning the village into a Protestant enclave.

During the wars of religion, in mid-16th century, this was a mostly Protestant village and was at one point set on fire and partly destroyed. It would be rebuilt bigger, better and more luxuriously, along with the wonderful Renaissance structure we know as the château today.

By 1685, the Edict of Nantes (which had given Protestants certain freedoms in this very Catholic country) was revoked and many (though not all) Protestant families fled, from here and from across France.

Lourmarin eventually became a prosperous little town, relying on manufacturing, handicrafts and agriculture. In addition to the olives and vines, the village was known for its textiles. In fact, Philippe de Girard, an illustrious (and local) engineer, invented the first flax spinning frame.

Today, Lourmarin Provence is a much-visited and quirky little village, with plenty of offbeat shops and surprising corners.

This was once the house of Philippe Girard, possibly Lourmarin's most illustrious citizen

This was once the house of Philippe Girard, possibly Lourmarin's most illustrious citizen One of Lourmarin's many intriguing fountains. This one has a pair of rubber boots pointing towards a quirky little bookshop just up the street: "This little bookshop, unlike others."

One of Lourmarin's many intriguing fountains. This one has a pair of rubber boots pointing towards a quirky little bookshop just up the street: "This little bookshop, unlike others."When in Lourmarin...

- Drop by Lourmarin market on Friday mornings – it's large for a town this size.

- The summer music festival at the château welcomes artists in residence every summer, with jazz, classical, ensembles...

- Wood sculptor Matthias de Malet has a specialty: he only uses certain types of local wood and each piece he carves is unique. Have a look.

- Book your accommodation in Lourmarin.

How to pronounce Luberon – or is it Lubéron?

My entire life I've pronounced the region Lubéron (lew-BAY-roh). And when I visited, it turns out I may have been saying it all wrong. Locally, people call it the Luberon, no accent: lew-BUH-roh. So which is it?

Locals say 'foreigners' (meaning Parisians) can go ahead and pronounce it with the accent on the "e"; I mean, they're foreigners and everyone knows it. But that doesn't end the debate.

Several French dictionaries allow both versions, so that doesn't help. According to certain stories of origin, the name comes from the Greek Louerio, which might hint at Lubéron. But then, in early literature, especially in the Provençal tongue, you'll find the use of the word Léberon, different yet again.

Another theory holds that to 'Frenchify' some Provençal words, the "é" (from Léberon) might have been switched to "eu" or simply "u", hence the "u" in the first syllable. Confused yet?

The consensus is that there is no consensus. With accent, without accent, pronounced one way or the other, it remains a fairy-tale land of suspended villages and medieval castles, cocooned by the cry of cicadas and the breeze drifting up from the Mediterranean.

4. Ménerbes

Coming upon Ménerbes is a bit like encountering a village clinging to the sky, high up a hill and built all along its crest. Expectations are high for this hamlet, given its status as an artists' magnet.

Unlike many other Luberon Provence villages whose dwellings crowd around a castle, Ménerbes is long and narrow, with the château at one end and the church at the other.

In Roman times, Ménerbes held a strategic position on the Via Domitia, the Roman highway that led from Rome to southern Spain. It is also famous for the Abbey of Saint-Hilaire, just outside town, which may have been founded by Saint Louis (Louis IX) upon his return from the 7th Crusade.

Because of its hilltop position, Ménerbes was long thought impregnable. But in a surprise attack, it was stormed and captured by Protestant Huguenots, who held it for five years from 1573 and were only driven out when a Catholic siege starved them of supplies.

That stunning view of Ménerbes, France as you drive up; you can clearly see the 12th-century citadel and its ramparts along the village.

That stunning view of Ménerbes, France as you drive up; you can clearly see the 12th-century citadel and its ramparts along the village.Today, Ménerbes has its place in the sun. Perhaps the best known contemporary advocate of Ménerbes was author Peter Mayle, who wrote A Year in Provence, his memoir set in the village.

But well before Mayle, artists had recognized the beauty of this south France village.

Like Dora Maar, a photographer and painter who became Picasso's muse and whose house (which he bought for her) is now an art foundation; the American painter Jane Eakin, whose home has been converted into a museum dedicated to her; or the French-Russian painter Nicolas de Staël.

We shouldn't be surprised, then, to find out the village's name may have come from that of Minerva, the Roman goddess of the arts.

Walking the streets (and looking out upon the valleys on either side) of the village, you can get a sense of the brilliance that brought so many creatives here. The quiet winding streets and blue shutters, the houses with greenery creeping up the walls, all of it under a crystal blue sky... the kind of languorous illusion these villages of the Luberon seem so able to provide.

It was closed when I visited so this is from the outside... one of the many fascinating art galleries scattered throughout Ménerbes (the two-dimensional art really caught my eye)

It was closed when I visited so this is from the outside... one of the many fascinating art galleries scattered throughout Ménerbes (the two-dimensional art really caught my eye)When in Ménerbes...

- For plants of all types, visit the Citadelle Botanical Garden (Le Jardin de la Citadelle): five hectares of truffles, aromatic and medicinal plants, herbs, edible plants... wander around and inhale.

- Then drop by the quirky Musée du Tire-Bouchon, the Corkscrew Museum, a fitting addition to a land so covered with vines. Who knew there is even a global association of helixophiles, or corkscrew enthusiasts!

- This area is known for a variety of products, like the black truffle or the much-loved AOC Côtes du Luberon wine. Drop by the Maison de la Truffe et du Vin to try both.

- Book your accommodation in Ménerbes Provence.

5. Roussillon

Think of Roussillon and you'll think of gold. Not the metal, the color.

Or ochre, because this is its birthplace: you'll see it on the walls, on the hills (and if you've been hiking the Ochre Trail, on your shoes).

Shades of yellow and gold and rust and deep blood red, as though ochre weren't a color but a hue, a slight hint of spark and fire.

➽ ANOTHER BEAUTIFUL VILLAGE?

Here's one that isn't part of the "five". Not only is it beautiful, but it has an amazing history of scandal. Read all about the village of Lacoste, where the Marquis de Sade once lived.

Scenes of Roussillon Provence, one of the most spectacular villages south of France

Scenes of Roussillon Provence, one of the most spectacular villages south of FranceRoussillon is one of those hilltop villages of Provence which is as beautiful from afar as it is up close. Watch the sun's rays play along the village walls, especially at sunset.

But from its streets, the progression of ochres will keep your eyes glued (and your feet tripping) as you try to understand how a single color can be so diverse.

Interestingly, there's a local law obliging residents to paint their façade in ochre; this makes perfect sense, because a blue or pink wall could severely mar the village's harmony. That said, I did pass by houses which, although painted ochre, were adorned with different-colored shutters, so these are clearly allowed.

Walking on ochre

If the village's explosion of colours – from beige to deep, burnt red – envelops you in an embrace of wellbeing (psychologists attribute the emotions warm, energetic and sunny to this colour), you might want even more than what buildings can offer.

Enter the Ochre Trail.

Stunning colors along the Ochre Trail in Roussillon, one of the best villages in Provence

Stunning colors along the Ochre Trail in Roussillon, one of the best villages in ProvenceNo one knows why Roussillon has all the ochre, and the other villages of the Luberon do not.

While there are a few legends that might explain this, what IS known is that during the 1780s, a native of Roussillon first studied the local phenomenon, and then started mining it commercially. He invented a process to extract the pigment from the sand, but it would take another century before the mining became widespread.

At first, individual miners produced ochre. But with the industrial revolution, big business got involved.

In its heyday, the tiny village of Roussillon had 16 quarries and ochre production plants! Things boomed with the arrival of the railway in Apt, the nearest provincial center, in 1880.

But by the 20th century, artificial colourings were the rage, competition became fierce and the mining industry disappeared.

Today, a single ochre mine is left in the region, the Mine de Bruoux in Gargas, a ten-minute drive from Roussillon.

When in Roussillon...

- Okhra, the Ochre Eco-Museum, promotes and protects the traditions linked to ochre and natural pigments. Hands-on workshops and guided visits.

- The Ochre Trail is a great way to experience ochre right in the heart of Roussillon: Just cross the main street of Roussillon (there really is only one) to the cliff and follow the path to the trail. Choose the 30min or 60min trail.

- Book your accommodation in Roussillon.

LUBERON TOURS AND TICKETS

➽ Half-day best of the Lubéron from Avignon

➽ Full-day highlights of the Lubéron from Avignon

Travel tips if you visit the Luberon

Here are a few travel tips and additional facts about the Luberon...

- The best way to see the towns of Provence and the Luberon is by car (although there are ways to visit the Luberon if you're car-free). Most of the villages don't have trains, and bus transport is sporadic. The roads are lovely (although a very few can be narrow in winding) and driving around here is a true pleasure. You can compare car rental prices here. The other option (but only if you're really good at it) is cycling.

- Plan your itinerary: the villages are small and quite close to one another. You can see several on a day trip if your time is limited.

- Look around at the amazing stonework. Not only is southern architecture harmonious, but it is compounded by the use of natural materials.

- Don't be surprised if you feel an air of Tuscany among these small French villages... the cypress trees are responsible!

- Vines, olive groves, lavender. Rinse and repeat.

- Wherever you go in this region, you'll be surrounded by the most beautiful villages in Provence. Below is a map of Provence in France, with a focus on the Luberon – the villages I described above, and many more worth a visit if you have the time!

Map of the prettiest towns in Provence

The Luberon region is part of central Provence, north of Marseille and to the east of Avignon, capital of the Vaucluse département. As for the Luberon, it is shared between the Vaucluse and the Alpes-de-Haute-Provence.

The entire Luberon is contained within the Luberon Regional Natural Park, which is filled with cycling and hiking trails.

FAQ Luberon

What is Luberon known for?

It is a stunning part of Provence famous for its hilltop villages, lavender and olive oil.

How long should I stay in the Luberon?

If you don't have a lot of time, you can visit on a day trip from Avignon, but you'd only be seeing a few of its stunning villages. With 3-4 days, you could visit the best towns in Luberon.

What are the Luberon villages?

These are the many villages that dot the area of France known as the Luberon, in Central Provence. Many of them are on top of hills, which adds to their authenticity and attractiveness.

Where is Luberon France? Is Luberon in Provence?

The Luberon is in central Provence, partly in the Vaucluse and partly in the Alpes-de-Haute-Provence.

Is Luberon worth visiting?

The Luberon is a delightful region which many people make a detour to visit. It has all many things people love about France – ancient hilltop villages, lavender fields, impressive vistas and quiet, winding roads. It happens to be one of my favorite regions of France.

Before you go...

Did you know that like the pandemic of 2020, an epidemic hit Provence in the 18th century – and they too built a wall, right here in the Luberon?

And if you're in the region for a bit and are interested in Vincent van Gogh, remember that he spent several years in Provence, one of them in Saint Remy de Provence, less than half an hour's drive from the Luberon, and the rest in Arles, a short half hour beyond that. You can follow in van Gogh's footsteps, which are signposted throughout the town.

Did you enjoy this article? I'd love if you shared it!