Fascinated by Gallo-Roman history? Click Here to download > > > Here are 6 ways Rome affected France

- Home ›

- Culture & Civilization ›

- Renaissance to Republic ›

- Museum of Burgundian Life

The Quirkiest Dijon Museum: A Peek at 19th-Century Burgundian Life

Published 22 September 2021 by Leyla Alyanak — Parisian by birth, Lyonnaise by adoption, historian by passion

History isn't just about queens and castles but also about everyday life, which is something the Dijon Museum of Burgundian Life highlights perfectly, with its street and shop replicas and tableaux of people going about their lives.

For those of you nostalgic for simpler times, a twirl through the Museum of Burgundian Life (Musée de la Vie Bourguignonne) will plunge you into Burgundy’s rural past with such realism you may be tempted to reach out and touch.

NOTE: Pages on this site may contain affiliate links, which support this site. See full Privacy Policy here.

Dijon, the capital of Burgundy, has a wealth of museums, from the Musée des Beaux-Arts (France’s second-largest after the Louvre) to the elegant Musée Magnin (located in the benefactors’ original home).

But by far the quirkiest is the one that walks you through 19th-century Burgundy, with exhibits that might well have been forgotten had it not been for the passion of a local lawyer who spent his life collecting the disappearing bits and pieces of his time, the everyday items or costumes under threat of modernity.

The ethnography of 19th-century Burgundy

The museum is located in an old monastery (more about that below).

After entering through the cloister, the bright sunshine of the city is suddenly cut off, and life-sized wax statues emerge from the cool darkness, like so many historical stills going about their daily lives: the teaching of a schoolboy, the rocking of a baby, a wedding, the waiting for a cauldron to boil, the greeting of visitors, all rendered moodily yet realistically with amazing attention to detail.

Resist the temptation to rush through; instead, take in the buttons on the blue smock, the smoothness of the earthenware or pewter cooking containers, the sewing box and the woven bed canopies. Each is a detail we’ve seen before and lodged in the corners of our memories, but which are now brought to life.

Follow chronologically as a baby grows into a boy who becomes a young man who eventually marries and has children, all portrayed going about their daily lives, a peek into a family as it was two centuries ago.

You could easily imagine the little boy being sent off to school, his little pot of wine and water to keep him warm along the way… the tools and containers his mother will use to make butter… the jars with which she’ll concoct her winter preserves… the heavy wood furniture in the bedroom and the heaters that will soon be filled with hot coals to keep the cold winter away.

The costumes alone would be worth the wait. Women at the time covered their bodies, their long dresses bordered by lace and an always-present apron, their necks covered by silk gorgets and their heads coiffed by a lace bonner. The men, too, covered their heads, but with straw or felt rather than lace.

All of this makes for an ethnographically fascinating exhibit, whose descriptions (in French) are written in (not always easy to read) calligraphy.

The streets of the city

Having met Burgundian families in their intimacy, we are now transported to their lives outside the home.

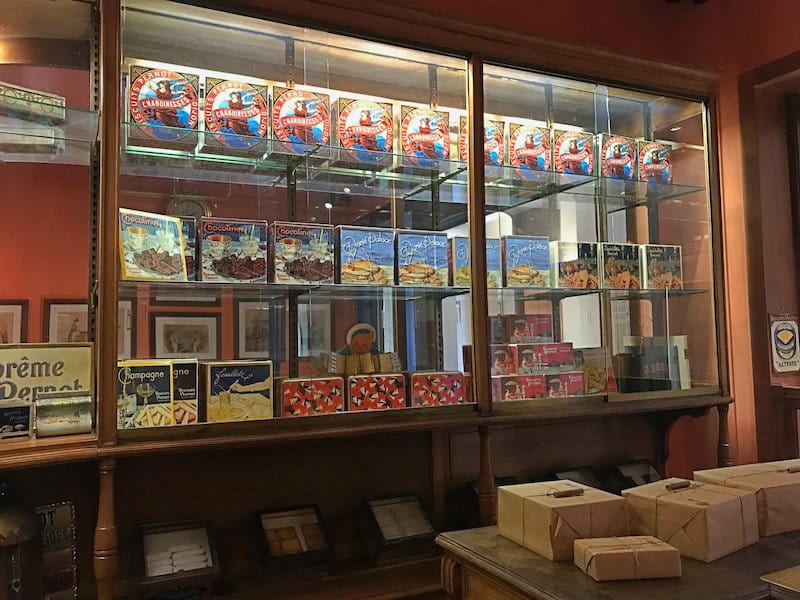

Aptly nicknamed the “Street of Time that Passes”, the museum’s second-floor alley carefully reconstitutes some of Dijon’s long-gone shops, plunging you into a ghostly 19th-century shopping spree. Here, the city’s industries are unpacked, like its mustards and ceramics and wine, an omnipresent industrial heritage at a time when the city is in full expansion with the opening of the Burgundy Canal and a train station. New businesses are constantly setting up shop in town, from biscuit-makers to ink manufacturers.

And let’s not forget all that Dijon mustard and wine.

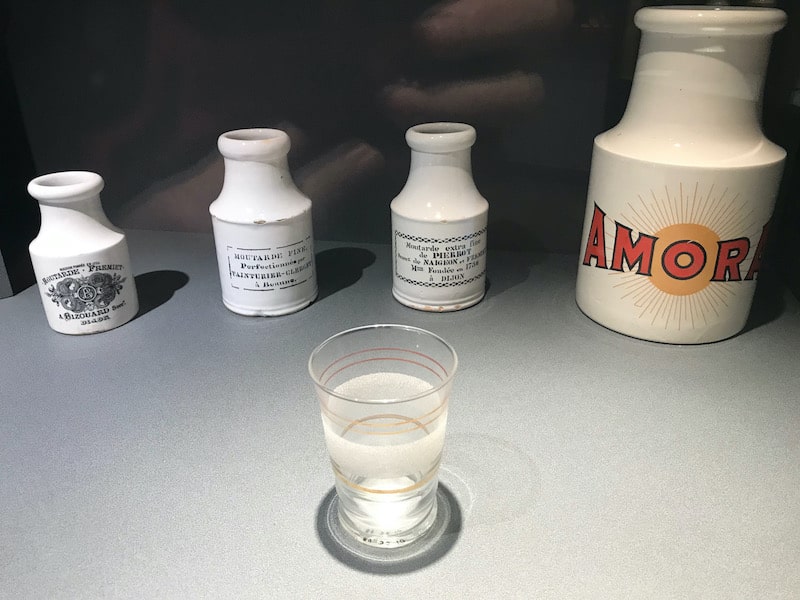

Top: old mustard containers. Bottom: locally manufactured ink bottles

Top: old mustard containers. Bottom: locally manufactured ink bottlesDuring the 19th century, shopping also changes, with goods increasingly shown in shop windows for all to see. To encourage customers, shops are building broad bays open to the street through which you can fix your gaze on that coveted item, and these shop windows are represented in the museum. You’ll find a furrier, a toy store, a clockmaker, a drugstore, a grocer, a beauty salon, a butcher, a cookie and candy store, a dry cleaner, and I’m sure I’m missing a few. To make sure you get the message, display ads begin to tout the multitude of products (you’ll find these ads in the museum as well).

Whether looking at the wax families or window shopping or reading up on the industries of Dijon, this museum is a fabulous example of history informing the present. By seeing how it used to be, you’ll better understand how it is.

A bit of history

I do love a bit of history so digging into the cloister’s past brought out some fascinating tidbits.

The cloister, as we know, was part of a Cistercian nunnery, the Bernardines Monastery. But it turns out the original abbey wasn’t in Dijon at all but in Tart-L’Abbaye, some 30km southeast of the city. It dates back to the 12th century, the first ever Cistercian nunnery, built back when Cistercians enjoyed prosperous times.

But that prosperity wouldn’t last, shaken by France’s turbulent Wars of Religion and reformist movements. Eventually, Cistercian communities began to disintegrate, their buildings crumbling and spiritual life eroding.

In 1618, a certain devout lady, Jeanne de Courcelles de Pourlans, joined the monastery. In the spirit of the Counter-Reformation, designed to fight the wave of Protestantism sweeping parts of France, she set about putting the place in order and reestablishing some discipline. And eventually moved the convent to Dijon.

There she began acquiring land and buildings to expand and over the years, the property would grow, the monastery would gain an additional two storeys, and several smaller buildings would be added.

But the French Revolution intervened, as it often did, and the anticlericalism of the time forced the nuns to abandon their monastery. The building became a military barracks, then headquarters for a short-lived religious cult, and finally, home to works of art originating in other monasteries raided by the Revolution. It later became a hospice for orphans, requiring yet more expansion. Several hospital services were located here (and would remain as late as 1983).

Dijon eventually bought the building. It became a national monument, was restored, and finally found its present calling as home to both the Museum of Sacred Art (in the chapel) and the Museum of Burgundian Life (in the cloister).

The Burgundian museum itself was the brainchild of a 19th-century lawyer, Maurice Bonnefond Perrin de Puycousin, who – like many of us today – noticed that modern life was pushing certain habits and items into obsolescence. Passionate about his regional heritage, he set out to document the local culture.

He began collecting oil lamps, as these were being replaced by gas lighting, and was soon gathering local furniture and clothes. He donated all of this to Dijon, but his museum collection gathered dust until it was relocated here, to the cloister, ready to show off rural life in Burgundy during the 19th century, and ready for us.

From quirky to sacrosanct

Right next door is the Museum of Sacred Art, in what was once the monastery’s chapel. It was opened to protect sacred artefacts found in rural Burgundy’s churches, items that were often at risk of theft or loss or the elements – or of simply being forgotten.

The church, like the cloister next door, is an architectural jewel, with its classical façade, doric columns, and circular interior, tropped with a copper cupola (before being covered in copper, it wore those stunning glazed tiles so in use throughout Burgundy).

One museum may be quirky, the other sacred, but both are out of the ordinary.

Additional information:

- Museum of Burgundian Life

- Museum of Sacred Art

- You can reach the Couvent des Bernardines on foot by following the Dijon Owl's Trail (Zola Branch), which guides you throughout the Old Town, or by hopping on the City Shuttle

You might also like these stories!

Pin these and save for later!

Did you enjoy this article? I'd love if you shared it!