Fascinated by Gallo-Roman history? Click Here to download > > > Here are 6 ways Rome affected France

- Home ›

- Destinations ›

- Paris ›

- Unusual Paris Museums

These 5 Paris Museums Are Rarely Crowded And Always Remarkable

Published 3 May 2025 by Leyla Alyanak — Parisian by birth, Lyonnaise by adoption, historian by passion

Paris has more than 130 museums, but visitors tend to make a beeline for the same four or five. Once you’ve seen them, you might be ready for some of the lesser-known ones, so I’ve highlighted five of my favorites — along with why I recommend you visit.

Sticking to the most popular museums — like the undeniably fabulous Louvre or Orsay — and avoiding some of the more niche ones means you’ll miss unusual (and quieter) institutions, filled with stories that may be hiding in plain sight.

I’ve chosen the five museums below because they’re a bit different, both for what they contain and for what they add to our understanding of Paris.

NOTE: Pages on this site may contain affiliate links, which support this site. See full Privacy Policy here.

These five museums won’t show you Paris at its most polished-but they will show you how it works, remembers, rebels, and reinvents itself.

From medieval tapestries to underground sewers and revolutionary relics, each one looks at the city from a different angle, helping us do what we want to do in Paris: learn more about it.

1. Paris in layers at the Musée de Cluny

I’d be lying if I didn’t admit this was one of my favorite Paris museums, mostly because there’s a sense of the ages you can almost feel through the stone.

The Cluny Museum, located in a 15th-century abbey, is known as the National Museum of the Middle Ages, although parts of it date back far earlier.

Our visit begins on a lower floor, in a vaulted chamber of what was once a Roman frigidarium, where ancient Parisians once bathed. Then, as we proceed through its various levels, you’ll emerge into a medieval world of prayer and pageantry, and… unicorns.

Brick and stone walls from the ancient frigidarium—part of the Roman baths beneath the Musée de Cluny in Paris. This cold room, once used after hot baths, is one of the best-preserved parts of the 3rd-century complex

Brick and stone walls from the ancient frigidarium—part of the Roman baths beneath the Musée de Cluny in Paris. This cold room, once used after hot baths, is one of the best-preserved parts of the 3rd-century complex In this tapestry from the Musée de Cluny, Arithmetic is shown as a woman teaching men to count using coins and a ledger. Female figures were often used to represent ideas, even though women rarely had access to this kind of education

In this tapestry from the Musée de Cluny, Arithmetic is shown as a woman teaching men to count using coins and a ledger. Female figures were often used to represent ideas, even though women rarely had access to this kind of educationEach object in this museum can spin a story: a gilded altar panel shows a royal couple kneeling before Christ; a group of 13th-century sculpted heads reminds us of the anticlerical fury of the French Revolution; and an intriguing fragment of stained glass shows two Medieval figures playing chess.

Ultimately, though, everyone here is headed in the same direction: towards the back of the museum to see the Lady and the Unicorn tapestries, a six-part allegory that’s been puzzling and delighting viewers since the 15th century. The story behind the tapestries is a bit mysterious, but if you want to understand it better, you must read The Lady and the Unicorn: it's fiction, but you'll be drawn along a world of weaving and Medieval society you won't get from a history book.

If you rush to the tapestries too quickly, though, you’ll miss the 2000 years of Roman stone beneath your feet, the carved saints overhead, and a quiet that somehow makes Paris feel ancient again.

These decapitated heads from the façade of Notre-Dame de Paris, once thought to be French kings, are actually the biblical Kings of Judah. They were rediscovered in 1977 and are now displayed at the Musée de Cluny

These decapitated heads from the façade of Notre-Dame de Paris, once thought to be French kings, are actually the biblical Kings of Judah. They were rediscovered in 1977 and are now displayed at the Musée de Cluny “À mon seul désir” is the sixth and final tapestry in the Lady and the Unicorn series at the Musée de Cluny. No one knows what it stands for but it is often thought to represent the lady’s free will—perhaps a renunciation of earthly pleasures or a conscious choice guided by emotions, not senses

“À mon seul désir” is the sixth and final tapestry in the Lady and the Unicorn series at the Musée de Cluny. No one knows what it stands for but it is often thought to represent the lady’s free will—perhaps a renunciation of earthly pleasures or a conscious choice guided by emotions, not sensesWhat to look for at the Cluny Museum

- The Lady and the Unicorn tapestries, often considered among the greatest surviving medieval works of art. Five depict the senses, while the sixth, “À mon seul désir,” remains enigmatic, its meaning unknown.

- The remains of the ancient Gallo-roman thermal baths (Frigidarium) from the 1st-2nd centuries.

- Its 13th-century heads, which once adorned Notre-Dame, were misidentified as biblical figures and destroyed during the (highly anti-religious) French Revolution, and finally buried until they were rediscovered in the 1970s.

- The Altarpiece of the Crucifixion is a 14th-century carved and gilded altarpiece showing a royal couple in prayer at Christ’s feet. Their rich garments, finely detailed faces, and nearness to the divine scene highlight their status and spiritual aspirations.

- A fragment of stained glass showing two figures playing chess, probably a reference to games of courtly love, where strategy and romance were often combined.

A man and woman play chess in this 15th-century stained-glass panel at the Cluny Museum. Here, chess becomes a stand-in for courtship and social status

A man and woman play chess in this 15th-century stained-glass panel at the Cluny Museum. Here, chess becomes a stand-in for courtship and social statusThe Cluny is located at 28 rue Du Sommerard in the 5th arrondissement. Nearby subway stations include Cluny-La Sorbonne (Line 10) or Saint-Michel or Odéon (Line 4).

🏛️ 🏛️ 🏛️

2. Musée Carnavalet: Paris remembered

The Carnavalet isn’t a museum of France — it’s a museum of Paris, covering the timespan from Lutetia to May 1968, and I have to admit it’s my favorite museum in the city.

The Carnavalet is housed in a pair of elegant connected mansions in the Marais, the Hôtel Carnavalet, a Renaissance residence built in the 1540s with sculpted façades by Jean Goujon, responsible for most of the sculptures at the Château d’Anet, where Diane de Poitiers once lived, and the Hôtel Le Peletier de Saint-Fargeau, a 17th-century townhouse featuring a grand staircase and one of Paris’s earliest elevators.

This amazing wooden console was once in the original Fouquet’s boutique on Rue Royale—a stunning jewel of 1900s Paris

This amazing wooden console was once in the original Fouquet’s boutique on Rue Royale—a stunning jewel of 1900s ParisEach section of the museum is dedicated to a period of Parisian history.

Among those I keep revisiting are the French Revolution and the Belle Époque, both of which are very present in the museum.

This is where you’ll find the original key to the Bastille, a model of the fortress itself, some of Marie-Antoinette’s personal belongings, and objects once touched by individuals destined for the guillotine.

There are Revolutionary pamphlets filled with urgent messages, scratched-out portraits of royals, and graffiti left by prisoners awaiting execution, all mementoes of the collapse of a world order.

And, possibly one of my favorite pieces, a pair of guillotine-shaped earrings (which, sadly, aren't always displayed).

During the Reign of Terror, Parisian women wore guillotine-shaped earrings and jewelry featuring miniature heads of Louis XVI or Marie Antoinette—both executed by guillotine—as strong symbols of Revolutionary fervor

During the Reign of Terror, Parisian women wore guillotine-shaped earrings and jewelry featuring miniature heads of Louis XVI or Marie Antoinette—both executed by guillotine—as strong symbols of Revolutionary fervorWEARING THE REVOLUTION

During the French Revolution, especially at the height of the Reign of Terror (1793-1794), a wave of political fashion swept across Paris — jewelry and accessories modeled on symbols of the Revolution.

Among the most striking were guillotine-shaped earrings, worn primarily by women. These were sometimes paired with miniature busts of Louis XVI or Marie Antoinette, whom as we know ended their lives under the guillotine.

Why this fashion?

- Political alignment: Wearing these items confirmed the wearer's loyalty to the Revolution and distanced them from royalist sympathies. Given the number of snitches and the massive surveillance, this could save their lives.

- Mourning or satire: This fashion also expressed loss or black humor, especially among those who had lost loved ones to the guillotine (more than 5000 died in Paris because of the Revolution, 2600 of them by guillotine).

- Trendiness: Like any strong symbol, the image of the guillotine became widespread. It appeared not only in jewelry, but also on snuffboxes, fans and combs, stamping Revolutionary ideals of liberty, justice and punishment onto everyday life.

And then there’s Haussmann, the Baron who redrew the map of Paris at Napoleon III’s behest. The wide boulevards he carved across the city destroyed entire neighborhoods. Carnavalet preserves pieces of them, including shopfronts and period rooms, to remind us that before the grand architectural façades, Paris was Medieval.

To me, the Carnavalet is a bit like a Parisian cabinet of curiosities: rather than looking at Paris from the outside, it’s a bit like rummaging through its drawers.

One of the many Revolutionary-era shop signs at the Musée Carnavalet, this painted wood sign for “La Bonne Renommée” (Good Reputation) features an angel offering a laurel branch to a profile of a sans-culotte, in true Republican style

One of the many Revolutionary-era shop signs at the Musée Carnavalet, this painted wood sign for “La Bonne Renommée” (Good Reputation) features an angel offering a laurel branch to a profile of a sans-culotte, in true Republican styleWhat to look for at the Carnavalet Museum

- Revolutionary artifacts such as pamphlets, graffiti and objects from the storming of the Bastille

- Haussmann-era interiors, with period rooms and shop signs salvaged from a lost Paris

- Proust’s bedroom, reconstructed from his original belongings — a glimpse into the life of Marcel Proust, the French novelist known for In Search of Lost Time, a monumental (and some say interminable) work exploring memory, time and Belle Époque Parisian society.

- Strange and whimsical signs, everyday oddities that once hung above Paris streets

The Carnavalet is easy to reach and can be found at 23, rue Madame de Sévigné in the 3rd arrondissement, Métro Place Des Vosges (Lines 1,5,8) or Saint-Paul (Line 1) — and there are plenty of others.

🏛️ 🏛️ 🏛️

3. Musée de la Préfecture de Police

There’s always a slight sense of excitement when entering a police station, however innocent one might be.

As I sat in the lobby waiting for our guide to arrive, my eyes darted furtively around the room, wondering whether some criminal might get hauled in, as we see so often on TV, or a stubbled detective, looking as unkempt as they do on screen (at least the French ones do).

After walking up some stairs, we emerge into a well-lit set of smallish rooms which house documents that cover two centuries of public order and disorder, from 18th-century manhunts to 20th-century espionage.

Created in 1909 by then-Police Prefect Louis Lépine, the museum was intended to train officers in the history and methods of policing.

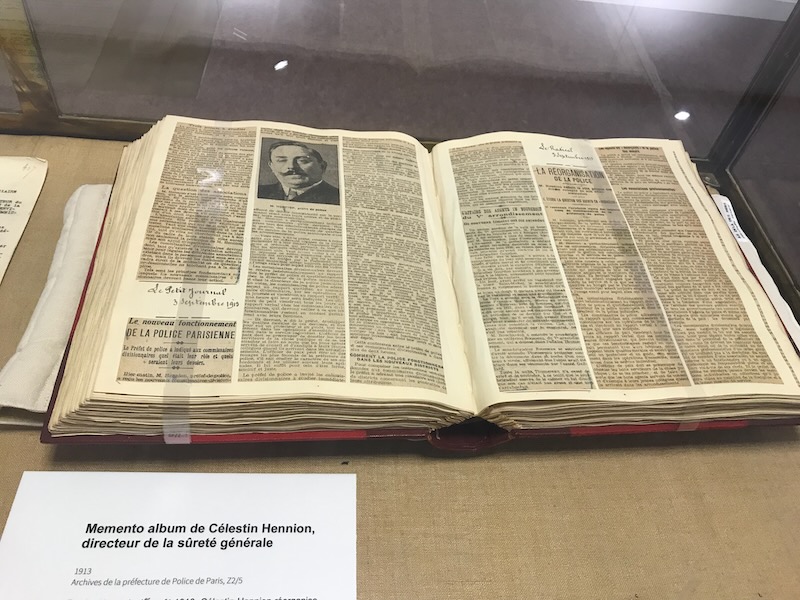

A 1913 scrapbook belonging to Célestin Hennion, director of the Sûreté générale, filled with newspaper clippings about police reform and public order. Part of the archives at the Police Prefecture Museum in Paris

A 1913 scrapbook belonging to Célestin Hennion, director of the Sûreté générale, filled with newspaper clippings about police reform and public order. Part of the archives at the Police Prefecture Museum in ParisYou’ll see a blade from the guillotine (an original), surveillance equipment used during the Occupation, mugshots of anarchists, and Resistance leaflets smuggled under the noses of collaborators. There’s a badge Jews were forced to wear under the Vichy regime, displayed next to maps of Paris used to organize roundups.

But it’s not all darkness.

The museum is also a record of technological change: from early fingerprint kits and breathalyzers to crowd-control devices and riot police armor. There’s even a section on the evolution of Parisian police uniforms, including some surprisingly ornate 19th-century examples.

The quietest objects here are often the loudest: a Vichy-era identity card, a prisoner’s note scrawled on a scrap of paper, a typewriter once used to forge documents. You can’t see these things without feeling some of the pain that created them, and even though both the tours and descriptions are in French, if police work interests you (for example if you read crime novels) you'll find plenty to see here.

A collection of Napoleonic-era military uniform accessories—insignia, cockades, epaulettes and ornamental details

A collection of Napoleonic-era military uniform accessories—insignia, cockades, epaulettes and ornamental detailsWhat to look for in the Musée de la Préfecture de Police

- The guillotine blade, a lot smaller than I’d expected

- Surveillance tools from the 1940s-60s, less sophisticated than today’s but chilling nonetheless

- Resistance documents including clandestine newspapers, forged IDs and radio equipment, along with Vichy-era materials including deportation maps and discriminatory laws (you’ll see this type of thing in many of the Resistance museums across France)

- Crime scene photography and forensic kits showing off early Parisian criminology in practice

- Police uniforms and gear, from ceremonial to riot-ready

TIPS FOR VISITING PARIS MUSEUMS

- Check the opening days — museums are often closed on Mondays or Tuesdays, and on certain major holidays.

- Don’t bring big bags: chances are they won’t let you in with an oversized backpack or something on wheels. A few museums have lockers but they’re usually small and won’t take a suitcase, so check first. Your best bet is to find a reliable luggage storage nearby.

- To avoid the crowds, go in the afternoon or a couple of hours before closing time.

- Where possible, buy your tickets online to avoid entire school classes in line in front of you.

The Museum of the Police Prefecture is in a police station at 4 Rue de la Montagne Ste Geneviève in the 5th arrondissement. The closest Métro station is Maubert-Mutualité on Line 10.

🏛️ 🏛️ 🏛️

4. Musée des Arts et Métiers: Paris’s temple of almost everything

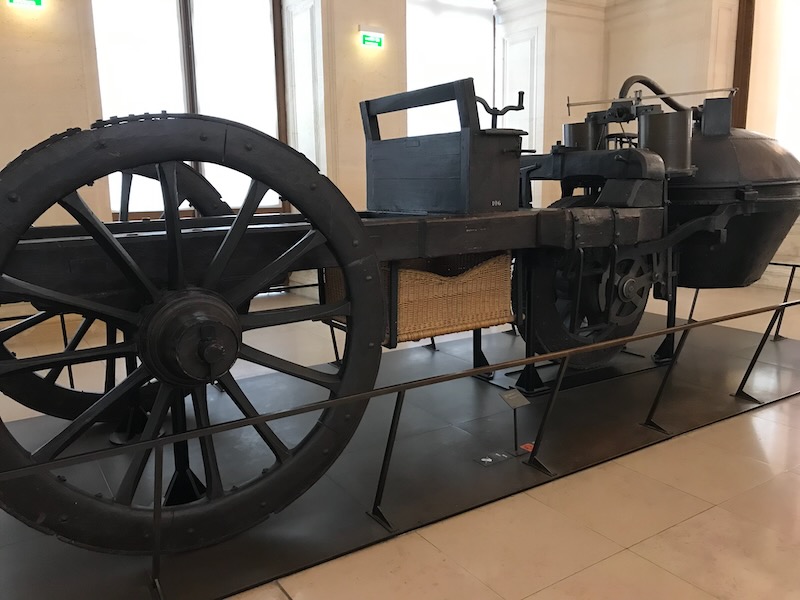

Cugnot’s 1769 fardier à vapeur, the world’s first full-scale self-propelled vehicle. It was powered by steam and originally designed to haul artillery, and marks the birth of automobile engineering

Cugnot’s 1769 fardier à vapeur, the world’s first full-scale self-propelled vehicle. It was powered by steam and originally designed to haul artillery, and marks the birth of automobile engineeringWhen I first walked into this museum, I thought it was about engineering, or machines. It IS, but is so much more: it’s a museum of the imagination, of ideas that shaped the world, or could have.

Founded in 1794 as part of the Enlightenment’s push to make knowledge more democratic, it now houses over 80,000 objects ranging from early scientific instruments and industrial prototypes to full-scale models of inventions that might have changed history (if only they’d worked a little bit better).

Early sound film equipment on display at the Musée des Arts et Métiers in Paris, including a 1930s phonofilm system that synchronized recorded sound with motion picture, part of cinema’s leap from silent to talking pictures

Early sound film equipment on display at the Musée des Arts et Métiers in Paris, including a 1930s phonofilm system that synchronized recorded sound with motion picture, part of cinema’s leap from silent to talking picturesThe museum is part of the Conservatoire National des Arts et Métiers (CNAM), a higher education institution devoted to science, engineering and applied research. It still has a higher education function, but its museum galleries are open to the public — and remarkably under-visited.

The museum visit ends in a former church, Saint-Martin-des-Champs, where airships and flying machines hang from the ceiling above worn stone floors.

A smaller original model of the Statue of Liberty by sculptor Auguste Bartholdi, part of the development process for the monument gifted to the United States in 1886

A smaller original model of the Statue of Liberty by sculptor Auguste Bartholdi, part of the development process for the monument gifted to the United States in 1886What to look for at the Arts et Métiers

- Foucault’s pendulum, still swinging in the Gothic church nave

- Cugnot’s 1770 steam carriage, the first motorized vehicle in history, too slow and energy-hungry to succeed, but still

- Clément Ader’s Avion III, a bat-shaped monoplane from 1897, which dangles midair in the old church nave. It never achieved sustained flight, but it paved the way for others.

- The original model of Bartholdi’s Statue of Liberty, used by him to raise funds and support. A second, cast in bronze, once stood in the courtyard but is now on long-term loan to the USA, where it sits in the French Ambassador’s residence in Washington DC.

- Blaise Pascal’s “Pascaline”, one of the world’s first mechanical calculators, invented in the 1640s when he was just 19.

- Perpetual motion machines — beautiful, intricate, and completely unworkable. Several are on display, reminders of how close invention can come to delusion

- Chappe’s optical telegraph, used during the French Revolution, a pre-electric system that relayed messages via semaphore towers strung across the countryside. Brilliant, but instantly obsolete once electricity arrived.

Léon Bollée’s 1889 calculating machine, one of the first to automate multiplication and division using a system of pinwheels and sliders

Léon Bollée’s 1889 calculating machine, one of the first to automate multiplication and division using a system of pinwheels and sliders Clément Ader’s “Avion III” (1897), a pioneering steam-powered flying machine with bat-like wings, an early but unsuccessful attempt at heavier-than-air flight

Clément Ader’s “Avion III” (1897), a pioneering steam-powered flying machine with bat-like wings, an early but unsuccessful attempt at heavier-than-air flightThis unusual museum is located at 60 rue Réaumur in the 3rd arrondissement, Métro Arts et Métiers, Lines 3 and 11. Make sure you take the subway — the station itself is stunning and a perfect introduction to the museum itself. You can buy your tickets here.

🏛️ 🏛️ 🏛️

5. Musée des Égouts de Paris-and the flow of water under Paris

The first thing that came to mind as I walked to the Paris Sewer Museum in the rain is “Boy, this is going to stink!” But the reception area was above ground, airy and modern, with no olfactory clue to what was on display below.

Once we went down, then yes, there was a strong, damp smell, but not the horrible “stink” your imagination had probably conjured up. So please, don’t let this fear prevent you from visiting one of the most unusual Paris museums dedicated to one of the oldest functioning sewer systems in the world. Just don’t forget to wear closed shoes — it is damp, after all.

A maintenance tunnel inside the Paris Sewer Museum

A maintenance tunnel inside the Paris Sewer Museum A cleaning boat suspended above one of Paris’s underground sewer canals, still maintained in part by boats like these that scrape and flush sediment from the tunnels

A cleaning boat suspended above one of Paris’s underground sewer canals, still maintained in part by boats like these that scrape and flush sediment from the tunnels Another cleaning boat. These heavy barges are floated through the tunnels to flush debris using the force of water behind them

Another cleaning boat. These heavy barges are floated through the tunnels to flush debris using the force of water behind themThe Paris sewer system dates back to the Middle Ages, but the modern network was built under Baron Haussmann and his engineer Eugène Belgrand in the 19th century. As Haussmann demolished and rebuilt the surface of Paris, Belgrand did the same below ground, creating a vast, gravity-powered system of tunnels that drained waste, prevented floods and protected public health.

At the museum, you walk alongside (and in places, directly over) a flowing sewer channel. Exhibits explain how cholera epidemics, urbanization and revolution all influenced Paris’s approach to sanitation. You’ll see models of manhole covers, early street-cleaning carts, and the massive and imposing iron dredging balls used to clean sediment from the tunnels.

FIGHTING CHOLERA UNDERGROUND

In 1832, a cholera outbreak killed over 18,000 Parisians in just a few months. At the time, sewage was dumped into cesspits or the Seine, also a source of drinking water. The link between dirty water and disease was poorly understood at the time.

That changed in the 1850s, when engineer Eugène Belgrand, working under Baron Haussmann, built a modern sewer system for Paris. It separated waste from drinking water, drained the streets, and delivered clean water to public fountains, eventually including the famous Wallace fountains.

Belgrand’s network didn’t just clean up the city: it helped stop deadly epidemics, and this is the story told by the Paris Sewer Museum.

These wooden cleaning balls, once rolled through Paris’s sewer tunnels, helped dislodge sludge by creating pressure waves in the water—an old but effective technique still used in parts of the system today

These wooden cleaning balls, once rolled through Paris’s sewer tunnels, helped dislodge sludge by creating pressure waves in the water—an old but effective technique still used in parts of the system todayWe don’t realize the importance of these underground tunnels — until they stop working, of course, or until they are misused. Bodies were thrown into the Seine during cholera outbreaks.

"The sewer is the conscience of the city. All the filth of the human species passes through it. It is not merely the subterranean drain—it is the evil that flows beneath the surface. A sewer is a cynic. It tells everything."

—Les Miserables by Victor Hugo

In 1944, Resistance fighters used sewer tunnels to evade capture. Victor Hugo gave Jean Valjean his unforgettable escape route through this system. (Hugo, who personally toured the sewers, used them in Les Misérables as the setting for the dramatic escape of the fugitive Jean Valjean.)

When the modern sewer system was expanded in the mid-19th century, Paris was entering the Belle Époque, an era of industrial growth and urban renewal. They were built on top of older drainage channels and mirrored the image Paris had of itself at the time: engineered, modern and rational. Other than the Catacombs, you won’t find another underground experience like this in Paris.

What to look for in the Sewer Museum

- Belgrand’s plans and diagrams, the blueprint for modern urban sanitation

- Massive dredging balls used to scour the tunnels

- 19th-century sewer worker tools like boots, hooks, and early safety gear

- Real flowing sewer channels, which you can hear, see, and smell

- Historical records of epidemics and uprisings that show the link between sanitation and survival

🏛️ 🏛️ 🏛️

Why these Paris museums matter

The Louvre and Orsay may the spotlight, but they don’t tell the whole story of Paris.

To explore the city's history, you'll need to experience its objects and the ideas that shaped it. These five museums will help you do that and will reveal a version of the city that feels authentic and less polished than the curated artworks and polish of the city's headline museums.

You'll need both types of museum to truly get under the city's skin.

All photos in this article ©OffbeatFrance

Did you enjoy this article? I'd love if you shared it!