Fascinated by Gallo-Roman history? Click Here to download > > > Here are 6 ways Rome affected France

- Home ›

- Destinations ›

- Paris ›

- Carnavalet Museum

How to Plan Your Trip To The Carnavalet Museum in Paris

Published 17 May 2025 by Leyla Alyanak — Parisian by birth, Lyonnaise by adoption, historian by passion

This article explores the Musée Carnavalet – Histoire de Paris, the city’s oldest municipal museum, essential for anyone who truly wants to understand Paris, its revolutions, its reinventions and its daily life through the centuries.

A pair of earrings stopped me cold.

They were delicate, almost pretty, until I realized what they were: tiny gold guillotines, blades poised mid-swing, suspended from dainty hooks.

These were actual fashion accessories and women wore them during the Reign of Terror – a period of mass executions during the French Revolution – either to show their support or just to stay alive. (I'm not sure which is more disturbing).

They usually sit quietly in a case at the Carnavalet Museum - Histoire de Paris, the capital's sprawling, often-overlooked archive of itself.

Why 'usually'? Because exhibits rotate and sometimes they're replaced by other items.

A sadly blurry photo of the guillotine earrings - and when I returned to take a better shot, I was told they had been put away ©OffbeatFrance

A sadly blurry photo of the guillotine earrings - and when I returned to take a better shot, I was told they had been put away ©OffbeatFranceUnlike many museums, Carnavalet doesn’t force-feed you what you need to know. Instead, it shows you what Paris has left behind, some of it unsettling, and lets you decide for yourself what to take away from it. It’s the closest thing the city has to a memory, which qualifies it as one of the more unusual museums in Paris.

NOTE: Pages on this site may contain affiliate links, which support this site. See full Privacy Policy here.

A museum of fragments

The Carnavalet isn’t grand in the usual sense.

It has no towering glass pyramid, and no crowds with cameras. It is a rather discreet establishment housed in two Renaissance mansions in the Marais neighborhood, not far from the Place des Vosges.

It opened in 1880 as the Musée de l’Histoire de Paris and reopened in 2021 after five years of restoration, a much brighter and more accessible place, but still a bit of a labyrinth.

And maybe that’s the point.

You don’t tour the Carnavalet, you wander through it, from room to room, wondering if you're headed in the right direction, only to pass the same exhibits two or three times.

Rather than the artistic genius we've come to expect in museums, this is a journey through the different stages of the city's history. You'll find household objects, protest signs, royal portraits, graffiti – if it happened in Paris at some point, chances are you'll find remnants of it here.

Curious about what you're seeing? Get the Carnavalet audio guide to help you understand this extraordinary museum.

Before we get to the exhibits, it helps to understand what this museum is trying to do. Paris has always been more than just a city, more of an idea or a symbol, and that idea has shifted throughout the centuries as it bounced between kings and revolutionaries, artists and bureaucrats.

This instability is captured by the Carnavalet through the things people left behind, revealing the accumulations of history. Some are tiny, from a pamphlet or a floor tile to a slogan scrawled on a well. All this adds up to this special collection of what Parisians have documented or tried to erase about themselves each time the city reinvented itself.

Here, then, is a loose interpretation of the seven ages of Paris.

1. Ancient Paris: Before there was a city

One of the oldest objects in the museum is a boat: a pirogue carved from a single tree, dating back to 2700 BC. Pulled from the Seine, it’s a reminder that this was once a watery land of fishermen and marshes.

The museum’s archaeological section showcases Lutetia, the Roman precursor to Paris, with mosaics, coins, and even a funerary stele for a Roman citizen named Lucius Julius.

These were the beginnings of Paris: muddy, commercial, and doused with the tart scent of wood smoke.

Part of the Roman collection of the Carnavalet ©OffbeatFrance

Part of the Roman collection of the Carnavalet ©OffbeatFrance2. Medieval and Renaissance Paris

From there, you move into the age of saints and stone.

Look for the statue of Sainte Geneviève, Paris’s patron saint, said to have saved the city from the Huns. Nearby are original gargoyles from Notre-Dame, 16th-century tapestries, and even a working astrolabe from the 1400s, a rare combination of art and astronomy.

There’s a portrait of King Francis I, whose Renaissance ambitions reshaped the French court by importing the Renaissance and giving Paris its first taste of grandeur.

Painting in the Carnavalet of Sainte Geneviève, Paris’s patron saint, protecting the city from the threat of Attila and the Huns

Painting in the Carnavalet of Sainte Geneviève, Paris’s patron saint, protecting the city from the threat of Attila and the Huns3. The French Revolution: A city comes undone

This is, at least for me, one of the most haunting sections.

This is believed to be one of Marie-Antoinette's shoes, rescued from the chaos of the Revolution

This is believed to be one of Marie-Antoinette's shoes, rescued from the chaos of the RevolutionThere’s a model of the Bastille, complete with key. There's graffiti scratched by prisoners and pamphlets calling for the king’s head. And those guillotine earrings, with their hint of violence.

The exhibits don't glorify or condemn the French Revolution – they just lay it out for you to decide.

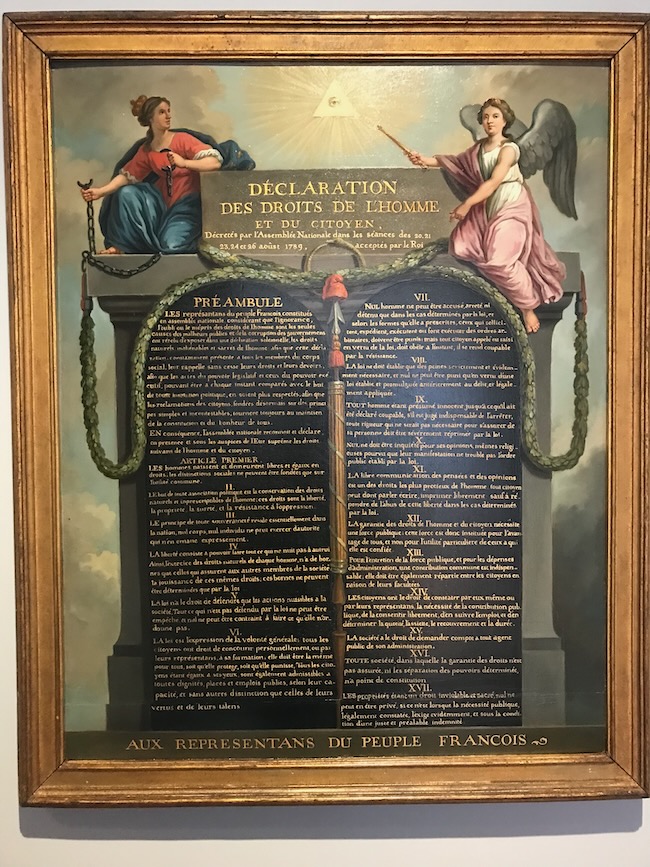

The 1789 Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen was an Enlightenment blueprint for liberty, drafted during the Revolution but still present in constitutions today

The 1789 Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen was an Enlightenment blueprint for liberty, drafted during the Revolution but still present in constitutions todayWHAT ARE THE SEVEN STAGES OF PARIS?

Historians sometimes speak of the seven stages of Paris. It is not an official chronology, but a useful framework for viewing the city’s constant reinvention:

- Roman Lutetia – A Roman settlement with forums, public baths, and straight roads that still influence the layout of the Latin Quarter today

- Medieval Paris – A city of churches and scholars, centered on Notre-Dame and the Sorbonne, with narrow, crowded streets

- Renaissance and Royal Paris – A period of royal influence, seen in formal gardens and grand architecture

- Revolutionary Paris – A city shaken by revolt, where the streets saw protests, executions and the birth of new political ideas

- Haussmann’s Paris – A massive 19th-century redesign that replaced medieval streets with wide boulevards, parks and matching buildings

- The Belle Époque – A time of lively cafés, cabarets and elegant design that covered up social inequality and growing colonial power

- 20th-century Paris – Shaped by war, resistance and protests, the city experienced occupation, liberation and the breakup of France's colonial empire

My own stages are slightly different but all in all, these are the phases through which we can see a Paris in perpetual movement.

4. Paris Rebuilt: Haussmann and the Second Empire

The next rooms jump to the 19th century and the radical urban surgery performed by Baron Haussmann under Napoleon III. Wide boulevards, uniform façades and gas lighting were all part of a controlled, modern Paris.

As Haussmann swept through, dwellings were levelled and the Carnavalet shows us what was lost: wooden shop signs, salvaged furniture, and entire rooms ripped from homes before demolition. It’s easy to admire Haussmann’s clean lines but harder to face their human cost.

There’s also a scale model of the Opéra Garnier, and photographs of the bustling Halles market, long before it became the sanitized Forum des Halles.

One of the many images at the Carnavalet of Paris before Haussmann began changing the face of the city

One of the many images at the Carnavalet of Paris before Haussmann began changing the face of the city5. The Commune and the Siege of Paris

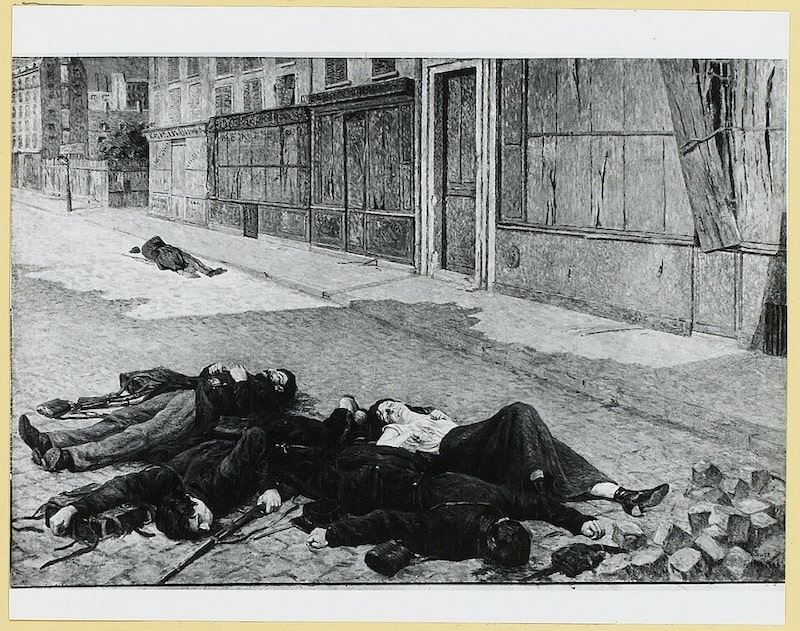

This is a darker room.

Here are shell fragments from the Prussian siege of 1870, a red flag from the short-lived Paris Commune (a worker-led government in Paris), satirical caricatures of politicians, and photographs of a revolt that lasted only weeks.

The people of Paris tried to govern themselves for a while, and failed. The Carnavalet lets us see what was left of that experiment.

6. Belle Époque and Art Nouveau

With the arrival of the Belle Époque, the "superficial" gaiety of Paris makes its entrance.

A gallery filled with paintings by Jean Béraud captures the bustle of boulevards and cafés. A poster for the Moulin Rouge screams color and energy. Another announces a new department store: La Belle Jardinière.

This is Paris in the age of spectacle and consumerism, elegant but scratch the surface and you'll find plenty of forces at play.

Fouquet's shop reconstructed at the Carnavalet ©OffbeatFrance

Fouquet's shop reconstructed at the Carnavalet ©OffbeatFranceFew rooms are more beautiful than the reconstruction of Georges Fouquet’s jewelry boutique, designed by Alphonse Mucha. All curves and light, it’s Art Nouveau at its peak.

You’ll also find Métro entrances by Hector Guimard, decorative vases by Émile Gallé, and a serene (but theatric) portrait of Sarah Bernhardt.

This is the Paris the world fell in love with — or thought it did.

A painting in the Carnavalet shows the Lapin Agile, a 19th-century cabaret in Montmartre that drew artists like Picasso, Modigliani, Apollinaire and Utrillo

A painting in the Carnavalet shows the Lapin Agile, a 19th-century cabaret in Montmartre that drew artists like Picasso, Modigliani, Apollinaire and Utrillo Sign for Le Chat Noir, Montmartre’s famous 19th-century cabaret and hub of bohemian Paris

Sign for Le Chat Noir, Montmartre’s famous 19th-century cabaret and hub of bohemian Paris7. The 20th Century: War, resistance and protest

The museum continues its travels into the 20th century with displays of World War I helmets, Resistance newspapers, and photographs of the Liberation.

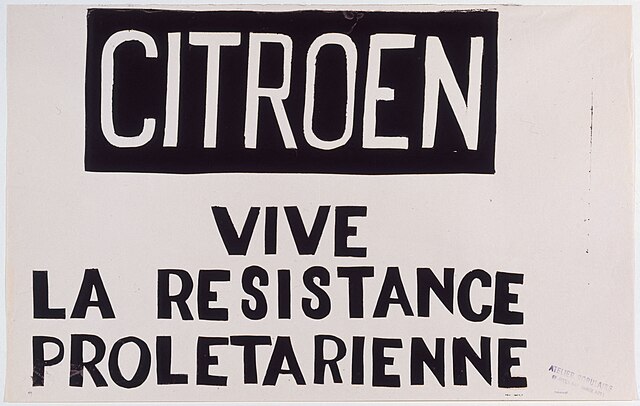

You’ll see posters from May 1968, calling students and workers to the barricades with their red and black slogans. Other displays reflect a more modern Paris of immigration and identity, with pride flags and the voices of new arrivals shaping the city.

Again, a reinvention, and Paris isn't finished yet.

Poster from the May 1968 protests at the Citroën factory, calling for support of the proletarian resistance during France’s nationwide worker and student uprising ©Atelier de l'Ecole Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts

Poster from the May 1968 protests at the Citroën factory, calling for support of the proletarian resistance during France’s nationwide worker and student uprising ©Atelier de l'Ecole Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-ArtsBefore you go

Despite its unbelievable richness, many visitors skip the Carnavalet, often because they don't know much about it. There are no Mona Lisas here, but there aren't long lines either.

If you want to truly understand Paris – not just the buildings but the people who lived and loved in them – this is where you go (here's their official website for all the practical information).

I'll admit it's not the easiest museum to visit. It can be a bit confusing, some rooms are quiet and unsettling, and others may be a bit overwhelming, a bit like memories: they're not neat and ordered, they stumble and often jump around. But if you truly want to understand what made Paris what it is today, this is a perfect starting point.

If you're keen on French history, make sure you subscribe to my free Substack, Gallia Incognita, for looks at the people and events that have made up France.

Did you enjoy this article? I'd love if you shared it!