Fascinated by Gallo-Roman history? Click Here to download > > > Here are 6 ways Rome affected France

- Home ›

- Destinations ›

- Southwest France ›

- Basque Products

7 Surprising Basque Products That are still made by hand

Updated 14 July 2024 by Leyla Alyanak — Parisian by birth, Lyonnaise by adoption, historian by passion

If you're going to the Basque country and love handmade products, I visited a number of shops and factories to track down traditional family businesses. From ceramics to clothes to sweets, I found many that continue to create unique items, fueled by passion and excellence and a desire for authenticity.

Are you fed up with seeing the same things in every store you visit? Or with cheap machine-made goods that crumble at first use?

When I was younger, things were meant to last. My mother would buy me a purse and ten years later, I'd still be using it.

Well, you can still do that.

In the Basque country of southwestern France, between the Atlantic and the Pyrenees and near the border with Spain, traditions mean something, whether you're talking about dance or food or games.

This is the land of the Basque people, whose origins are nebulous, whose language is unique and unrelated to any other living language, with an ethnic makeup different from that of their neighbors. Everything in their history has set them apart from others, from geography to politics.

Their one constant is authenticity.

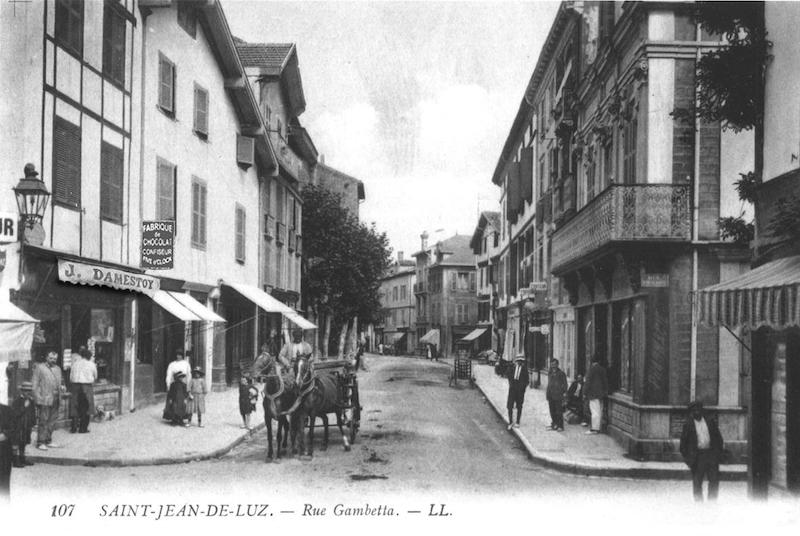

Damestoy, the founder of the House of Pariès in 1895

Damestoy, the founder of the House of Pariès in 1895Here, the fact that a family has been around for centuries counts for something.

That they are perpetuating a skill or art that was learned at grandmother's knee is a matter of pride. The modern world may be useful, enjoyable even — in fact, Basques are great travelers.

But what really counts is what comes from home.

NOTE: Pages on this site may contain affiliate links, which support this site. See full Privacy Policy here.

Quintessentially French: le béret basque

Whenever someone who isn't French thinks of us, there's usually a French stereotype involved. Chances are, it includes either a baguette or a beret, or both.

As a teenager I had quite the collection, including a lime green one I particularly liked and a navy one my mother favored. With long hair flowing, I looked positively sophisticated, a perfect circle of felt perched on my bright red mane.

"The Béarnais shepherds used it 400 years ago to protect themselves from the weather," said Jean-Michel Gibert, manager of the Laulhère shop in Saint-Jean-de-Luz. "It was a question of quality over quantity. A beret could be handed down in a family for years."

As you might have gathered from the use of the word Béarnais, the beret isn't exactly Basque. It came over from Béarn next door, but, as the Basques say, they're the ones who improved it and made it into what it is today.

So it's theirs.

This particular adventure began in 1840, when Lucien Laulhère started a linen and wool shop. He also happened to make berets, which became wildly popular after one was offered to Napoleon III and Empress Eugénie. Soon, everyone was wearing a beret and of course they were being called 'bérets Basques'.

Laulhère just kept going, as did his sons after him. Soldiers wore berets as part of their uniform, and the style spread throughout the population.

Laulhère shop in Saint-Jean-de-Luz: the firm has been making berets since 1840

Laulhère shop in Saint-Jean-de-Luz: the firm has been making berets since 1840But a combination of factors almost ended it all.

During the 1960s, hats of any kind were uncool, and the end of the draft in France in the 1990s nearly pushed the Laulhère firm out of business

Two of the beret's main markets had been wiped out: fashion and the military. The company filed for bankruptcy, but someone bought it — entrepreneur Rosabelle Forzy.

"It would have been incredibly sad to lose this 180-year-old firm and all its unique know-how," she said.

And she somehow put this traditional item of Basque clothing back on the map. Modern marketing techniques are finding new uses for berets, as part of rugby club uniforms, for example, or in haute-couture.

A beret may look simple (a round piece of felt, right?) but it is actually quite complex to make and takes 2-3 days for a single piece, using techniques that haven't changed much since the 19th century.

Here's what's involved:

- knitting of the finest virgin merino wool, a complex process because of the beret's round shape (today this is done by machine)

- darning to join the circular edges

- felting, which makes the beret denser and more water resistant

- dyeing by master dyers according to a top-secret formula

- shaping by placing two wooden half-circles inside the beret

- ennobling to bring out the fluffiness

- finishing, such as an inside satin strip, a leather band to hold it on, a ribbon or a multitude of fashionable details

- grooming, the final stage, where every last detail is checked — again.

Next time you wear a beret, consider everything that went into making it... look at the impeccable finish and the beautiful trim.

And choose the color you want, no matter what anyone says. There's nothing wrong with lime green. (And yes, you can buy a Laulhère beret online.)

HEADED TO THE BASQUE COUNTRY?

➽ Here's my perfect one-week Basque itinerary to see it all!

Surely you've heard of Basque linen?

I'm sure you've seen Basque linen before, but you may not have recognized it as such. Pretty striped cloth, right?

But it wasn't always so. Once upon a time, this cloth protected beasts of burden from flies and heat. Along the way, someone noticed it was pretty and had the smart idea to put it to other uses — tablecloths, tea towels and espadrille vamps (the top part of the shoe).

A traditional bolt of Basque cloth always has seven stripes of various widths, one stripe for each of the seven Basque provinces, the four in Spain and the three in France.

Those seven stripes were originally green and red, a combination that today would probably only work well around Christmas. Now, we like more muted colors, like hues of grey, burnt orange or bordeaux.

I visited the Lartigue 1910 workshop (the company, one of the region's first fabric workshops, was set up in 1910) and met the man in charge, Philippe Lartigue. He told me his fourth-generation enterprise happens to be the oldest company in this part of France and he took the time to show me around (I had just missed the daily tour). This video gives you an idea of the process that goes into weaving the cloth.

Cheap Chinese imitations are the bane of the Basque linen industry, but identifying the real thing isn't that difficult: just go to the Lartigue 1910 website and look at their prices. Then compare with what you're finding in the shops. If you've come across a table cloth at half the price, it is a fake.

If you buy some cloth (even a dishcloth) remember that basque linen is initially very stiff: you'll need to wash it a few times before you use it. As I have wisely done with my own tablecloth.

Inside the weaving workshop at Lartigue 1910

Inside the weaving workshop at Lartigue 1910Huge, glorious ceramic pots (their secret: rope!)

When I first walked into Goicoechea in Saint-Jean-de-Luz and saw these enormous pots, my immediate thought was: "How can I fit one into my suitcase?"

They were huge, they were stunning, they were elegant. I walked over gently (you don't want to send one of these flying) and wondered out loud... how on earth could they be made a meter high?

"Avec des cordes," said Terexa Goicoechea, a member of the family-owned business, "With ropes."

I got the very smallest tiniest one...

I got the very smallest tiniest one...The process hasn't changed since family patriarch, Jean-Baptiste Goicoechea, threw the first of these pots in 1960. Instead of using a mold, he used a wooden frame and coiled a thick rope around it.

It's still done this way today.

As the pot turns, the clay is thrown on. Once the surface is smooth, the inside frame is removed and only the rope stays, with the clay now stuck to it. What follows is a more traditional pottery process but the result is astounding — if you peer inside one of the pots, you'll still see the imprint of the rings of rope.

Their factory is in the village of Ossès but their shop in the center of Saint-Jean-de-Luz is more than enough to show off what they do.

Of course I couldn't resist. I bought a LITTLE one. But I'm sure that big black one staring at me from the back has my name on it...

Rope isn't just for ceramics: it's for espadrilles too

Like every French teenager, I spent my growing years with espadrilles on my feet. They were cheap and cheerful and you could match them with everything. Red dress? Red espadrilles. You get the picture...

And a big plus — you could wear them both on the beach and in town, so no extra sandals to carry around.

Fast forward, and little has changed.

The Basque artisans who make espadrilles still produce them exactly the same way their ancestors did (well, there might be a machine or two to help things along but mostly, the process is the same).

What you would wear today — soles of braided jute and a linen top — is what you would have worn 100 years ago, except perhaps for the colors: traditional espadrilles came only in black or white (for Sundays). They were worn by miners and priests, and were considered a poor man's shoe.

No one quite knows where or when they originated although some claim the espadrille was around as far back as 1322 in northeastern Spain.

By the 18th century, they were common in the French Basque country and remained in wide use in the 20th century — Spain's dictator, General Franco, decided they would do just fine for his armies and so his troops went off to war wearing espadrilles.

Popular personalities have been spotted wearing espadrilles: US President John F. Kennedy as a young man on the beach, or actresses Lauren Bacall and Grace Kelly (once Grace became Princess of Monaco, she probably didn't wear them as publicly).

Then Yves Saint-Laurent added heels and ribbons, and the rest is history.

Personally speaking, I prefer the traditional flat kind because I find the wedges a bit unsteady and I've fallen off them before...

More recently, espadrilles were made to measure for President Barack Obama and his wife Michelle (navy for him, purple for her).

While most espadrilles are plain and flat, fashionable styles have turned this simple shoe into a must-have summer wardrobe item

While most espadrilles are plain and flat, fashionable styles have turned this simple shoe into a must-have summer wardrobe itemLike many of the small family businesses around here, the Basque espadrille industry has to fight the influx of low-cost imitations mostly from China, although education (the imitation espadrilles are glued rather than sewn) and strict labeling rules have helped somewhat.

These days, five espadrille manufacturers remain, mostly around the town of Mauléon. One of the best-known is Don Quichosse, a fourth-generation firm, and these photographs trace how they make their espadrilles.

I also visited a Prodiso shop (in the Errecart family since 1977) where I was given a few hints about how to wear them and how to tell the real thing from the fake.

If you've ever worn a pair of espadrilles, you'll know they tend to slip off the back of your feet. Well, there's a secret to stopping that, apparently: get a smaller size!

If you buy them tight, they'll quickly stretch around the toes but won't slip off your heels. (I bought two pairs and am now testing this theory.)

Leatherwork and nails

You know that feeling of walking past a shop — and reversing your footsteps?

That's what happened to me on the rue Gambetta in Saint-Jean-de-Luz, when I walked past... THIS.

You can never have too many leather bags, my little internal voice said...

I desperately wanted to go inside and talk to the staff about how these were made but the shop was so popular customers kept filling it and I didn't get the chance.

Maison Laffargue has been here since 1890 — right here: the original workshop is next to the store, and still in operation. This is where they make the smaller items, like wallets. A larger workshop opened in 2017 in the nearby village of Ascain, for belts and Basque handbags.

The firm is now managed by a fourth-generation Laffargue and carries a special label: "Entreprise Familiale Centenaire", which is awarded to family firms that are over 100 years old.

And here's another one that is clearly meant for me:

Notice the studs on the leather — they are typical of Laffargue and made of a type of nickel known for its shine. Every stud is made in-house and fastened one at a time by hand, and the leather (from French tanneries) is selected and cut by master leatherworkers.

Perfection.

For the sweet-toothed among us

At some point you will be hungry and you will want to taste the famous Basque cakes. Trust me on this. But wait until later in the day because once you have a portion, the only thing you'll want to do is nap.

I visited not one but TWO specialty bakers, both in operation for generations, with everything carefully made by hand. And for research purposes only, I tasted gateau Basque in both. The jury is still out and I shall have to return for further experiment.

Chosen alphabetically, the first bakery on my list is Maison Adam, which I love for the crazy chocolate displays in their windows. When I visited the theme was African wildlife and the chocolates looked like lions!

But I digress. Adam, on the rue Gambetta (I'm beginning to feel like the rue Gambetta is the center of the universe), has produced fine macarons since 1660. Yes, you read that right: 1660.

This noble house created special macarons in honor of Louis XIV's wedding, which took place a few meters away, in the Eglise Saint-Jean-Baptiste. Today's macaron recipe is the same as the original, and when you bite into a macaron, you'll be sampling exactly what the Sun King did all those years ago.

Of course there's a secret ingredient in the macarons, whispered through the generations, but no one outside the family knows what it is. I did ask, though...

What a gateau Basque, or Basque cake, looks like

What a gateau Basque, or Basque cake, looks likeThe other bakery is the fifth-generation Pariès, also on rue Gambetta (bien sûr!)

They also have their own macaron, called a muxu, but this one was created by mistake. It was 1948 and one of the workers showed up exhausted for his shift, having stayed up to party late the night before. He used the wrong quantities of sugar and almond powder and since both were expensive, he decided to keep the mixture. Pariès tweaked the recipe... and so the muxu was born.

Even more dangerous is the kanouga, a very more-ish fudge: if you buy several squares, please be forewarned that said squares will all be gone by the time you reach the next street corner. Bear this in mind and buy at least twice as many as you normally would.

And if you haven't had your gateau basque yet, or if you'd like to try a different version, there be chocolate cake here!

The founder of the Pariès bakery, Jacques Damestoy, was a city worker in Bayonne when he fell off a ladder in front of the shop of Mrs Cazenave, the famous chocolatière (more about her in a minute). Once he was back on his feet, she offered him a job, which he kept for five years before branching off on his own, and the rest is history. Today, his descendants run the family business and continue in the same tradition.

Did somebody say... chocolate?

Cazenave tea room... it can't get much more romantic than this, and look at that stained glass ceiling! I can see myself celebrating a special occasion here (with lots of chocolate)

Cazenave tea room... it can't get much more romantic than this, and look at that stained glass ceiling! I can see myself celebrating a special occasion here (with lots of chocolate)Now, about Madame Cazenave, or at least her tea room... because every good chocolate comes with a story, right?

First I should mention that the city of Bayonne is where chocolate made its first appearance in France, at a 17th-century wedding. In this case, it was Louis XIV's father, Louis XIII, who was getting married. The chocolate must have hit the spot because by the time of Louis XIV's court in Versailles, it was being consumed regularly.

By the 18th century, anyone in Bayonne who could afford one had a chocolate-making machine.

Now the Cazenave chocolate shop and tea room isn't exactly a family affair — at least not the same family.

It all started in 1854 when 22-year-old Pierre Martin Cazenave opened his chocolate shop. Eventually he sold it to the Biraben family, already well-known chocolatiers. At the turn of the 20th century, two female employees bought the shop from Mrs Biraben and for the next 60 years, the new owners upheld the chocolate-making tradition with the help of their husbands and then their children. One of the owners' grandchildren bought out the other and today, more than a century after their grandmother waited tables at Cazenave, they own the shop.

Little has changed. Not the chocolate. Not the elegant tearoom decor and bespoke china. Not the stained glass ceiling.

Hotel Arraya: a family affair

The quiet streets of Sare at night

The quiet streets of Sare at nightWaking up to find a deer scampering across your garden isn't something you see every day but in Sare, at the Hotel Arraya, that's exactly what happened.

The hotel sits in the heart of Sare, one of France's most beautiful villages. Even under the clouds and rain, Sare sparkles. My room faced the back garden, and the countryside, and... the occasional deer.

This village, like many other parts of the Basque country, was made fashionable by Empress Eugénie who would visit, and ride to the top of La Rhune mountain on a donkey or a mule (you can now do the same in the comfort of one of the few remaining rack railways in France).

Orson Welles stayed here in 1955 and decided the Basque country had so much charm and harmony he made a film about it (it's still on YouTube if you search).

And I couldn't resist sneaking in a shot of my bedroom at the Hotel Arraya in Sare

And I couldn't resist sneaking in a shot of my bedroom at the Hotel Arraya in SareI chatted with Jean-Baptiste and Laurence Fagoaga, the third generation of Fagoagas to manage the hotel, and found out how it all got started.

The 16th-century building was once a pilgrim stop along the St James Way and at some point began housing families.

Jean-Baptiste's grandfather had a shop next door and his father and aunt decided to convert it into a tea shop. It was bound to be popular — both his father and uncle were pelote champions (Basque pelota is a game resembling jai alai). This of course attracted customers, the tea room grew into a restaurant and, eventually, into this hotel.

Jean-Baptiste's family have been here for centuries and he grew up in this building, in a part of the house whose original rooms still exist. After a stint at the Lutetia in Paris and some humanitarian work in Bosnia (he ferried diapers, money and food to Mostar on the front lines), he felt the pull of his homeland.

"This kind of experience opens you up, and you end up thinking, France isn't so bad, and it's good to come home," he told me.

Before you go...

One of the reasons we travel is to see things that are different from those we know, whether it's handicrafts or style or original know-how.

We also love to bring home things that are special, that no one else will have, and that's why I love handmade goods. I know an item is unique. I also know it will be well made and, probably, last forever. Plus, by shopping locally, I make my own modest contribution to the local economy.

Because let's face it: there is no guarantee these family firms will survive.

I've mentioned the threat of competition from foreign imitations, and of course a big business who wants to can always undercut a smaller one. All this was compounded by the Covid-19 pandemic, which hurt small businesses, many of which had to lay off staff.

In normal times, several networks and schemes exist to help them flourish.

The Cercle des Créateurs Basques, the Circle of Basque Creators, is a small group of families and entrepreneurs who try to keep some of these traditions alive.

The EPV label, Entreprises du Patrimoine Vivant, or traditional enterprises, promotes products 'made in France'. The state awards the EPV label to small- and medium-sized businesses who have proven their traditional skills and know-how (here's the list).

Despite the good intentions, keeping traditional businesses alive is a challenge.

So if you visit the Basque country and are in the mood for some amazing sweets, a special gift with a history or a fabulous night's rest, you know what to do. Go local.

Did you enjoy this article? I'd love if you shared it!