Fascinated by Gallo-Roman history? Click Here to download > > > Here are 6 ways Rome affected France

- Home ›

- Destinations ›

- Lyon ›

- Fun Facts About Lyon

31 Weird, Whimsical And Wonderful Facts About Lyon, France

Updated 11 January 2024 by Leyla Alyanak — Parisian by birth, Lyonnaise by adoption, historian by passion

Lyon is a city of many facets: gastronomy, industry, history. But these 31 facts about Lyon, France, will show you just how whimsical this traditionally staid city can be. Let's look at some of these quirks and foibles.

Lyon seems to be the capital of everything: Gaul, silk, gastronomy, invention, oddities − and if you scratch just a little, you'll unearth plenty of eclectic or unusual facts.

How many cities can boast about using a barge for a morgue? Or having received alien visits not once, but twice?

NOTE: Pages on this site may contain affiliate links, which support this site. See full Privacy Policy here.

At the risk of dumping an irretrievable cliché right on your lap, Lyon is a city of contrasts, and each time I walk around, it hits me even more.

The city's two hills represent opposites: Fourvière Hill, with its Basilica, is the hill that prays, and Croix-Rousse, with its silk heritage, is the hill that works. It has two rivers. And it has both a well-heeled bourgeoisie and a huge working class reservoir.

Lyon was settled by the Celts, formally founded by Rome, expanded by the Gauls, enriched by the Renaissance, industrialized by silk − and a city whose chapters are still being written.

But it is a fun city, a lively and energetic city, one with textures for its many faces, and regularly considered one of the most stunning cities in France.

Lyon, a mixture of styles - and what remains of the Roman aqueduct

Lyon, a mixture of styles - and what remains of the Roman aqueductLyon the immortal

By immortal, I mean the ancient, the many historical facts about Lyon (France), from the centuries behind us, and the many still to come.

1. Lyon − or Lugdunum − was the capital of Gaul

In Roman times, Lyon – at least Fourvière, the ancient part – was called Lugdunum and everything that came from Rome heading towards the northern colonies transited through here, making the city a crucial crossroads. The fact that two rivers, the Rhône and the Saône, meet here positions the city strategically at their confluence.

You can still see plenty of what they left behind – amphitheaters, baths, bits and pieces of walls and columns, among some of the best Roman ruins in France.

When in Lyon, things to do include visiting Roman ruins, like this extraordinary amphitheater and historic site

When in Lyon, things to do include visiting Roman ruins, like this extraordinary amphitheater and historic site2. Lyon's basilica is built on a former Roman forum

The Basilica of Notre-Dame de Fourvière, high on the hill above the Roman ruins, was built on top of the Roman forum of Trajan. But there's nothing Roman about the Basilica itself. Rather, it is a whimsical mixture of Byzantine and Romanesque, with some striking mosaics and marble work.

Basilique Notre-Dame de Fourvière, seen from below. Going up to admire the view below is one of the fun things to do in Lyon

Basilique Notre-Dame de Fourvière, seen from below. Going up to admire the view below is one of the fun things to do in Lyon3. Lyon was home to both the Gestapo and the Resistance

During World War II, Lyon was the Nazis' regional military command for South France and a Gestapo headquarters. It was also a stronghold for the Resistance, who used the city's many secret passageways (known as traboules) to get around.

Lyon the mystical

Lyon has plenty of secrets that would qualify it as mystical and yes, the city has indeed been the venue of some quite strange goings on.

4. The Holy Grail may have been brought through here

The Île Barbe, possibly named for the Barbarians who may have founded it, is a tiny piece of inhabited land in the middle of the Saône River, with a few vestiges and homes (and a gastronomic restaurant – this is Lyon, after all).

Charlemagne, King of the Franks in the 8th century, decided to safeguard all his manuscripts and relics in the island's abbey, establishing its sacred bona fides. So it should not come as a shock that the cup of the Holy Grail may even have transited through here...

The Abbey at Ile Barbe

The Abbey at Ile Barbe5. Aliens may have landed in downtown Lyon

It's impossible to know how this idea surfaced but it has been around for a while. Rumour has it extraterrestrials may have landed on the city's main square, Place Bellecour, during the 9th century.

According to another source, the year was 832 when four Lyonnais were seen emerging from a UFO. After catching their breath and (sort of) coming to their senses, they announced they had been taken to a planet filled with ice and deserts. Of course they were immediately accused of witchcraft and narrowly escaped burning at the stake because the city's bishop intervened.

Yet centuries later, on a dark October night in 1621, a round object appeared in the dark skies, zig-zagging and emitting bolts of lightning. Could this be the beginning of another contact?

Either way, in 2015, the Raelian sect – which firmly believes in extraterrestrial life – gathered on the square to propose Earth's first ever alien embassy representation. Right here, on Europe's largest pedestrian square. Had it been built, this would definitely have been one of the best things to see in Lyon.

6. Nostradamus predicted several events in Lyon − correctly

Nostradamus, the mid-16th century seer and astrologer (under the patronage of Catherine de Medici), was a regular in Lyon. At the time, the city was a major printing center and Nostradamus a prolific writer. Among his many predictions were some worthy of note about Lyon.

In 1642, he predicted two conspirators would be decapitated on the Place des Terreaux during a visit by Cardinal Richelieu, Louis XIII's right-hand man.

This turned out to be true.

He also predicted Pope John-Paul II would die in Lyon, so when the pope visited in 1986, local authorities, unwilling to dismiss the prophecy, beefed up security to make sure the pope stayed safe.

He did.

Lyon the slightly weird

Beyond the mystical, there is plenty about Lyon that will make you raise an eyebrow or turn up the corners of your mouth.

7. Lyon is home to one of the world's oldest astronomical clocks

Built in 1379 (or 1383, depending on whom you read), this particular clock sits in the northern transept of Saint-Jean-Baptiste Cathedral. It was vandalized in 2013 but the community rallied and donations paid for the repairs.

Astronomical clocks are fascinating. This one covers the ecclesiastical calendar (all the Christian holidays) and has a perpetual calendar that includes things like moons, saint feast days, and Gregorian and Roman calendars. You can also find out all about the signs of the zodiac, the tropics and the meridians.

8. There was once a crocodile

The year was 1745 and somehow, a crocodile escaped from a ship near Marseille (one could wonder what the crocodile was doing there).

The beast swam up the Rhône and settled under a bridge in Lyon, from where he amused himself by overturning boats, presumably to lunch on their passengers.

Two prisoners on Death Row offered their services to capture the reptile in exchange for freedom. The did eventually catch it, and the crocodile is now stuffed and on exhibit at the Museum of Civilian Hospices.

9. And then there was the floating morgue on the Rhône River

Floating morgue on the left [1862-1909] (AML, 4FI/9262)

Floating morgue on the left [1862-1909] (AML, 4FI/9262)Speaking of dead bodies and the Rhône... Keeping dead bodies on barges at the hospital's door may sound like a practical idea, but you have to wonder. Still, in the mid-19th century, such a floating morgue did exist, home to the city's dead bodies – until a flood in 1852 carried the dead downstream.

Not to be beaten, local authorities built a new barge. It quickly became the place to see and be seen on Sundays, with families crowding the nearby bridge to watch the floating dead. In 1910, it happened again, and the barge was carried quite a ways downstream.

That was it. The city was beaten: half a century of floating bodies was enough.

10. Lyon has its own "Eiffel Tower"

At a distance, you'd think this was a replica of the Eiffel Tower. Of course as you get closer, you'll notice this is a mini version (80 meters as opposed to the Eiffel Tower's 324). Plus, the satellite dish on its side is a bit of a giveaway.

In fact, it was built to accommodate a restaurant during Lyon's 1894 World's Fair, and it is said that Eiffel himself may have had a hand in its design (there is no confirmation of this). Today, it is a communication tower but also a conversation piece right next to the Fourvière Basilica.

Taking the funicular up to the Fourvière Basilica is one of the top things to do in Lyon, France. Right next to it you'll find this mini Eiffel Tower

Taking the funicular up to the Fourvière Basilica is one of the top things to do in Lyon, France. Right next to it you'll find this mini Eiffel Tower11. Dubai wanted to recreate parts of Lyon

In the flashy heyday of Gulf riches, a wealthy Emirati fell in love with Lyon and decided to rebuild part of the city − in Dubai. Agreements were signed, massive plans were drawn up, and cranes moved in, but then the economic crash came and the project was postponed. And postponed. Shame. It would have been entertaining to see some of Lyon's best sights replicated in the Middle East.

Lyon the innovator

Lyon can claim plenty of inventors and inventions, and these easily translate into creativity.

12. The hot air balloon was invented in Lyon

The Montgolfier brothers were industrialists from central France. While one brother worked in Paris, the other was in Lyon and they wrote back and forth. The Lyon brother, Étienne, drew up a small paper balloon, which he launched in 1783 fueled by scrunched paper and olive oil.

It worked, and he built a bigger one and the following year, some 100,000 Lyonnais watched as seven people dangled from the first hot air balloon for a full 12 minutes.

13. The Guignol puppet was born here

One of the best things to do in Lyon with kids (or without them!) is go to a puppet show.

A familiar figure in France, both among children and adults, the guignol may be Lyon's most famous citizen.

The puppet had unusual beginnings, in 1808. When Laurent Mourguet lost his job as a silk worker (the silk trade suffered as a result of the French Revolution), he became a tooth puller (at the time, this required no professional training) and to attract and distract customers, he used a puppet.

Soon, the puppet brought in more customers than the dentist and a star was born. Needless to say, our versatile Laurent left toothpulling behind and dedicated himself to the theater.

Guignol's most famous character is Polichinelle who, along with a few sidekicks, is dedicated to the triumph of good over evil.

Today, Guignol shows continue, whether in Lyon's puppet theaters or in some of the museums.

One of the interesting facts about Lyon, France, is that the Guignol puppet show was invented here. (Claude-Louis Desrais Public domain via Wikimedia Commons)

One of the interesting facts about Lyon, France, is that the Guignol puppet show was invented here. (Claude-Louis Desrais Public domain via Wikimedia Commons)14. The first veterinary school was founded in Lyon

It's true. In 1762, the world's first veterinary school was founded in Lyon, with the support of Louis XV. It was followed by another in Paris two years later.

15. Lyon helped jumpstart the art of sewing

Of course this is the Capital of Silk, helped along by the inventiveness of its professionals.

The Jacquard loom was invented by its namesake Joseph-Marie Jacquard in 1804. This loom made it possible to weave complex designs in a fraction of the time and brought down the cost of these cloths, making them widely affordable. Its use of perforated cards establish it, to a certain extent, as the (very distant) ancestor of the computer... or perhaps the robot. Progress has to start somewhere.

Another invention, with far-ranging impacts, was the sewing machine: in 1829, a tailor called Barthélemy Thimonnier designed the first ever sewing machine. It was made of wood, and had a moving arm to imitate the hand movements of a seamstress or tailor.

Both men patented their inventions.

16. Lyon's hospice had a revolving door for foundlings

Life in the past was often difficult and many newborns were abandoned in the city's streets, with parents unable to care for them.

The Hospice de la Charité made it easier to leave children: it built a wooden cylinder, a bit like a revolving trap door, with one opening on the street and another facing the hospice. When the cylinder turned, a soft bell could be heard. This allowed mothers to leave their children at the hospice discreetly. Terribly sad, but better than the alternative...

Lyon the artist

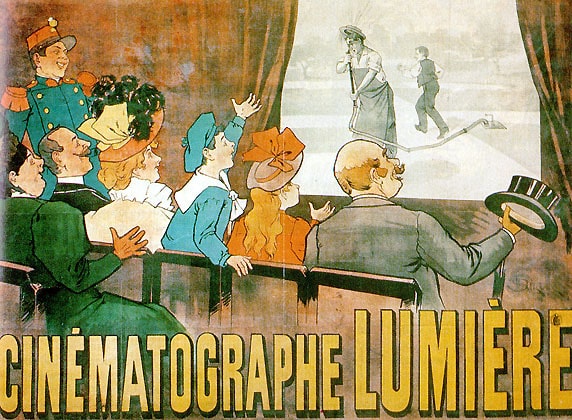

17. Lyon is the birthplace of cinema

Or at least, we think so, although Americans claim that title for Thomas Edison. This may technically be correct: Edison's built his kinetoscope, or peep-hole viewer, in 1891, but it allowed only one person at a time to watch moving pictures.

The Lumière Brothers created the cinematograph in 1895, but their moving pictures were projected and could be watched by everyone in the room.

Both sides of the Atlantic still claim the invention of motion pictures. Have a wander through the Institut Lumière and you can judge history for yourself.

One of the cool things to do in Lyon is to trace the history of the cinema. (Marcellin Auzolle Public domain via Wikimedia Commons)

One of the cool things to do in Lyon is to trace the history of the cinema. (Marcellin Auzolle Public domain via Wikimedia Commons)18. The creator of the Statue of Liberty also built Lyon's best-loved fountain

This is one of those fun facts about Lyon, France.

In 1857, Bordeaux decided to build a fountain on the Place Quinconces. It launched a contest and a young sculptor, Frédéric Auguste Bartholdi, won. He was 23.

But Bordeaux changed its mind, and went with another artist... who built a not too dissimilar one - the Fontaine des Girondins - which you can see on the Place Quinconces today.

Bartholdi went on to design New York's Statue of Liberty.

In 1886, the city of Bordeaux contacted him again. And again decided it didn't want the fountain.

Bartholdi decided to go ahead anyway and finished it, exhibiting it at the 1889 World's Fair in Paris. It caught the eye of the then mayor of Lyon, who sent in his negotiators.

Eventually, after quite a few financial tugs of war, the fountain was brought to Lyon, where it still stands today on the Place des Terreaux (although its position has been altered slightly from the original due to renovation work on the square).

Bartholdi's fountain on the Place des Terreaux in Lyon

Bartholdi's fountain on the Place des Terreaux in Lyon19. Lyon was the silk capital for the world for centuries

The silk trade was at the heart of Lyon's dizzying growth during the Renaissance, and the city can thank King François I for the privilege: in 1540, he gave Lyon the silk trade monopoly.

By mid-17th century, Lyon was so dependent on silk that the industry supported a third of the city's population.

This success would last until the Industrial Revolution, when the first artificial materials began making their appearance and edged silk out.

One of the things to do in Croix-Rousse, Lyon, is to follow the silk trail: museums, workshops, silk shops...

20. 80% of the muralists who paint Lyon's famous frescoes are women

Lyon's 150 trompe-l'oeil murals are world famous, painted by a Lyon artists' cooperative, CitéCréation. Walking through the city looking for these huge and stunning frescoes is one of those enjoyable alternative things to do in Lyon.

Four in five of the artists behind these magnificent frescoes are women.

Two of Lyon's many fabulous murals - looking for them is one of the great free things to do in Lyon ©OffbeatFrance

Two of Lyon's many fabulous murals - looking for them is one of the great free things to do in Lyon ©OffbeatFrance21. France's first workers' strike was in Lyon

Like most strikes, this one was about salaries.

November 1831 saw the explosion of the Revolt of the Canuts, as the silk workers were called. Up on Croix-Rousse hill, where all the silk work took place, the weavers decided to form an association − forbidden by law at the time − calling for a minimum wage.

The silk merchants refused and the workers struck.

The National Guard opened fire on the striking workers, but the tide turned and the workers pushed back the soldiers. For ten days they would rule Lyon, until reinforcements came and the government made promises (which it wouldn't keep, prompting another revolt in 1834).

This first industrial action is considered a crucial turning point in French history and revealed the deep cleavages among the workers and the bourgeoisie, paving the way for the rise of socialism and communism.

22. The Little Prince was written by a Lyonnais - but published in the USA

Who hasn't heard of Le Petit Prince? It's one of the most translated books in the world (into 300 languages) and tells the story of a pilot who crash lands in the desert and meets a boy from another planet (here's a quick plot summary). In the end, it's really about humanity and life.

It is a French classic, written by a French aristocrat, writer and pilot from Lyon. Except it wasn't written in France at all but somewhere not too far from New York City. After the Armistice, which divided France into two zones, Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, the author, traveled to the US to help convince the Americans to enter the war on the Allied side. Upon his return, he resumed active duty before disappearing at sea during a flight in 1944.

His book was published in France posthumously, in 1946, and is the biggest-selling French book of all time. Not written in France.

Lyon the gourmet

Lyon is known as the capital of gastronomy and one of the most popular things to do in Lyon is, well, to eat.

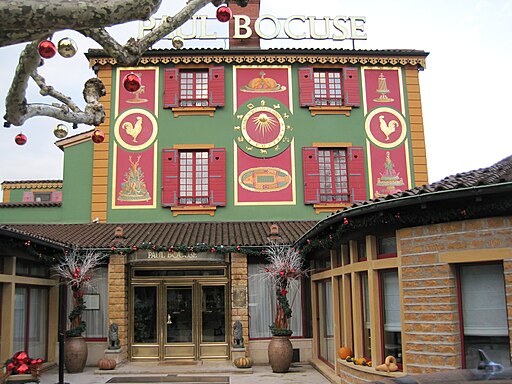

23. Paul Bocuse was from Lyon

Known as the Pope of French Cuisine, Bocuse made history with his Michelin stars (see next story below) and his name has become synonymous with excellence in French cuisine.

- He became one of the foremost proponents of Nouvelle Cuisine (I forgive him).

- He trained many chefs who themselves became world famous.

- The Bocuse d'Or is the world's most prestigious award for chefs.

- Les Halles Paul Bocuse is an essential stop on any foodie visit to Lyon.

- Along with Gérard Pélisson, Paul Bocuse founded the Institut Paul Bocuse, the renowned culinary arts and hospitality training school.

- Bocuse received many awards in his life, including the Légion d'honneur, France's highest distinction.

- In 1975 he created the soupe aux truffes, truffle soup, for a dinner at the Élysée Palace for then-President Valéry Giscard-d'Estaing.

24. Lyon's best restaurant has been the best for the longest

Lyon has the restaurant which has garnered the most accolades for the longest amount of time.

Paul Bocuse's Auberge du Pont de Collonges held its three Michelin stars for a whopping 54 years, longer than any other. Bocuse died in 2018 and didn't live to see his third star taken away...

25. Lyon boasts the first woman chef to get three stars

Eugénie Brazier, born in the Bresse region, opened a typical Lyon restaurant – a bouchon – in 1921 (it's still in operation today, although she is not). She was awarded three stars in 1933 for La Mère Brazier.

She was one of those Mères de Lyon, or mothers of Lyon, who immortalized Lyonnaise cuisine, which evolved from eateries for the city's many silk workers.

She also passed on her skills to the younger generation, including a certain Paul Bocuse.

Delightfully fun facts about Lyon

Lyon is famous for many things, the kinds of things visitors to the city cannot leave without seeing. Some of these would find their place on a simple list of things to do in Lyon, others on a list of things you should know about Lyon. Either way, these are part of what makes Lyon the city it is.

26. Lyon has more than 500 secret passageways

These are called traboules, and were initially created to help bring water from the riverside to the citizens living on the city's hills. The passageways were also used to help keep the bolts of silk dry during Lyon's many rains, allowing the material to arrive at port from the workshops pristine and dry. More recently, they helped members of the Resistance escape the Gestapo during World War II.

A very few dozen remain open to the public, and you can walk in a door on one street and emerge in another, making this one of the most intriguing things to do in Vieux Lyon and in Croix-Rousse, the two areas where most of the passageways are located.

Sadly, they are slowly closing their doors. They still exist, but are being outfitted with digital keypads, allowing residents to enter but no one else.

Some of these date back to the 4th century, while others are far newer, and no two are the same. A few are tunnels, others courtyards, and yet others are stairways. Since most of them lead to dwellings, make sure you tiptoe!

These medieval traboules are Lyon, France landmarks ©OffbeatFrance

These medieval traboules are Lyon, France landmarks ©OffbeatFrance27. Lyon's funiculars, built in 1862, are still working

One of the top 10 things to do in Lyon is to take the funicular and see the city from above, a fabulous view of Lyon, which you've probably seen on Instagram.

From Old Lyon, you can ride two 19th-century funiculars up the hill to either Fourvière Basilica or the Roman Amphitheaters. Just a hundred years ago, Lyon had five of these lines. Lyon is quite hilly, some of the hills are steep, and using animals to haul merchandise was costly and took time. The funiculars changed all that...

28. A tenth of Lyon is protected as a UNESCO World Heritage Site

Or, the equivalent of 427 hectares (1055 acres).

Since 1998, four districts of Lyon have been designated part of the World Heritage Sites: Old Lyon, Fourvière, Croix-Rousse and parts of the Presqu'ile, representing the Gallo-Roman period, the Renaissance, the Industrial Era and the 19th century.

This is a spectacular listing as it covers 162 buildings in an area that is home to 60,000 people.

29. A whopping 325 of Lyon's monuments light up at night

Lyon illuminated at night ©OffbeatFrance/Anne Sterck

Lyon illuminated at night ©OffbeatFrance/Anne SterckLyon has come to be known as the Capital of Lights and one of the best things to do in Lyon at night is to take a memorable stroll through its brightly lit splendour.

Many of Lyon's majestic monuments are illuminated, making the buildings dance in the night, the first city in Europe to launch this kind of lighting project.

When it comes to lights, Lyon is perhaps best known for its four-day Fête des Lumières, each year in early December. This Festival of Lights has been replicated across France but it started here, in Lyon.

Why the lights?

Back in 1852, Lyon was in turmoil and it was decided to erect a statue of the Virgin Mary on Fourvière Hill to calm things down. Scheduled for 8 September and postponed to 8 December because of poor weather, the Lyonnais placed candles in coloured glasses on their windowsills to "accompany" the statue on its walk up the hill, turning the façades into multi-coloured light shows. And the tradition, celebrated each 8 December, remained, transformed into veritable works of art.

Lyon is the Capital of Lights, more than ever.

Lyon's Festival of Lights. This creation is called Tricolore - Ralf Lottig ©Muriel Chaulet

Lyon's Festival of Lights. This creation is called Tricolore - Ralf Lottig ©Muriel Chaulet Pigments de Lumière - Nuno Maya & Carole Purnelle ©Muriel Chaulet

Pigments de Lumière - Nuno Maya & Carole Purnelle ©Muriel Chaulet30. Lyon attracts more business visitors than tourists

Shocking, I know, but nearly two-thirds of all visitors to Lyon come here for business, not tourism.

Lyon is home to Interpol, the international police organization; Euronews, the European-wide TV news network; the International Agency for Research on Cancer; major banks, as well as chemical, pharma and biotech companies.

Many of these business visitors stay awhile to see what else the city has to offer: while Paris is France's most visited city, Lyon is number two, usually tied with the Catholic pilgrimage town of Lourdes.

One of the interesting things to do in Lyon, France, is to visit the modern Cité Internationale ©OffbeatFrance

One of the interesting things to do in Lyon, France, is to visit the modern Cité Internationale ©OffbeatFrance31. There's buried treasure in the Parc de la Tête d'Or. Honest.

Known as the "Lung of Lyon", this is the city's most magnificent park: it has one of the world's largest botanical gardens, with 16,000 species, and one the biggest rose gardens. Come summer weekends, Lyonnais and their families head for the Tête d'Or and its lake and zoo.

And, possibly, a bit of a treasure hunt.

Because there's a legend: A Christ with a gold head – or skull – is said to have been hidden in the park during the Crusades, buried by Crusaders or Barbarians back in the days when this was unkempt countryside.

Apparently, as ground was being broken for the park in 1857, a worker's shovel hit something hard and everyone thought it was the skull. A massive fight ensued and Christ, upset about all this violence, began to cry, first a river of tears, and then a lake, the same lake that graces the park today.

Belief in this legend was so strong that the city even called on a medium to try to locate it.

And that's how the park came to be called Tête d'Or, which means "head of gold".

No gold has ever been found.

Parc de la Tête d'Or - it certainly looks like a likely venue for treasure!

Parc de la Tête d'Or - it certainly looks like a likely venue for treasure!Lyon Hotels

Did you enjoy this article? I'd love if you shared it!

|

|